Issue 34 April 2013

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 22-23 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Tawny Owl feeding on carrion

Danny Arnold

Chairman – Teme Valley Wildlife Group

Much has been written about our native Owls. Certainly information on the Barn Owl is very well covered in literature, the Tawny Owl, perhaps a little less so. So it was with some surprise that I had the following occur here at Birchfield, my home patch in Upper Rochford, NW Worcestershire. It was an event that was not even on my birding radar.

Some years back, possibly 2008, we took the top out of a sprawling ash tree that was in the valley beside the house. Being in the valley, it was struggling for light, surrounded by trees on the valley sides. As a result of light competition, it had developed many off shoots from the base and was a lanky multi spindled specimen. Where we cut off these tall shoots, some 20 feet up from the base, they acted as supports to hold aloft the 1.5 x 2m platform we put in place, predominantly made out of pallet wood.

(Picture 1)

So for the last few winters, we have, whilst driving around the area on our travels, stopped to pick up fresh (non pan-caked) road kill, comprising mainly of rabbits and pheasants, which we put on the platform for the local Buzzard population to partake of. Over the years, we have had some great photographs of Buzzards coming down to feed and from the markings on the birds, we can tell that the one, probably a female, has been coming down from the very first year we put the platform up. Last year ‘she’ was occasionally joined,by another much smaller ‘male’? bird that has this winter also become a regular visitor to the ‘raptor table’ as it is now known locally. Both birds have very distinctive markings which we have been able to photograph and compare with the luxury of time and a computer.

In the early days, we tried waiting it out in the purpose-made bird hide which we built to overlook the raptor table, but the birds always seemed to know someone was there, however much we camouflaged the openings in the hide. But there was no doubt that the road kill was disappearing whilst we were not about. Eventually we purchased a trail camera, a small battery-driven unit that takes a picture when an infra red detector sensor is triggered. One of the advantages of the trail camera was that we could use it close to the raptor table. It was strapped to the top of a rustic pole secured at the base so it just looked over the platform, twenty or so feet in the air. This unit was triggered by all sorts of things including Robins, Great-spotted Woodpeckers, Great Tits, squirrels and the like, that all used the raptor table to perch on. Eventually we photographed Buzzard coming down and from the record of triggering the unit we found that Buzzards often came down at certain times during the day. This led us to being able to be in the right place at the right time and we soon managed to get some nice DSLR photographs of the Buzzard(s) feeding on the deposited road kill.

(picture 2)

The trail camera is also capable of taking a moderately good quality 30 second video, triggered in the same manner. So over a period of time, we have gained a lot of information about the way in which Buzzards can strip and devour a carcass and indeed, the interaction between two Buzzards after the same meal.

Of late, the trail camera is used mainly to keep an eye on how many different individual Buzzards come down to the table. Once the video clips have been checked, and if there is no ‘new information’ on them, they are now usually deleted, as we have a library full of them.

Right at the beginning of March 2013, we had a real cold snap. The two resident Buzzards had been coming down for road kill during the day for a period of over a week or so. Then on 1st March, the camera triggered on its infra red setting and began to record in complete darkness. With the camera being so close to the platform and automatically changing to the infra red camera setting for night time recording a Tawny Owl was clearly seen, having landed on the raptor table. This had happened occasionally in the past, with the Owl sitting perched there for a while, before taking off. On this occasion however, it walked over to the dead pheasant carcass and began feeding.

(Picture 3)

Initially, it came down and then started to feed for about three minutes, setting the camera off three times (The video duration was set to 30 seconds, with the lapse time set to 15 seconds between triggers). Three hours later it returned, but this time for 30 minutes, triggering the camera consecutively over 20 times (with a couple of very short stays away). It then disappeared for four hours, before coming back for 30 minutes. It then disappeared again for an hour and a half, before making its final visit of the night, which was literally, just one 30 second trigger of the camera.

On the second night, it came down for around 40 consecutive minutes, departed for 40 minutes, then returned intermittently throughout the next 40 minutes.

On the third night, it rained and the camera didn’t trigger at all, presumably because the Owl wasn’t out.

On the fourth night, the Owl came down for a full hour and ten minutes, with one six minute disappearance mid-session. There were no further triggers that night.

On the fifth night, it came down for an hour and five minutes, disappeared for an hour and fifteen minutes before its final return for a fifteen minute feeding session.

It did not come down any of the subsequent 10 nights.

On each occasion, the Tawny Owl is clearly seen tugging at feathers and eating both the feathers and flesh of the carrion. It used its beak to tear the flesh whilst using its feet to hold the carrion down in very much the same manner as the Buzzards. Unlike the Buzzards however, the Owl was much more wary of its surroundings. It would feed for voraciously for ten or fifteen seconds, then just stand still, head turning occasionally, looking around, for similar amounts of time.

It is conjecture as to what was going on, but it would appear firstly that the Owl clearly learnt that food was available at this site and it remembered where the site was, night after night.

At the times of disappearance from the raptor table the Owl was presumably hunting for more usual food like voles, mice and shrews etc? Or was it just resting up in a more secure and less open location, having fed itself on an easy meal? Or was it returning because it had been unsuccessful in finding rodent prey, or because it was just feeling hungry again after gorging itself earlier? All questions we cannot answer. But if we speculate, the cold weather may well have pushed small rodents deep into their burrows below ground, unavailable to owls, so it could well have been a lack of usual food supplies that induced this feeding behaviour. Clearly it was learnt and had become somewhat habitual.

Literature does make reference to Owls taking Carrion in the wild, but it is very scant in detail. I got in touch with several of my contacts in the birding world, but the vast majority had never heard of this behaviour, let alone seen it. This included a quite senior member of the BTO and several very respected RSPB contacts as well as many more local contacts. Most came back with the same few references that I and others had found, but the common theme was that there was very little detail written down about this feeding behaviour. A search of the internet likewise turned up very little information about this subject.

As part of my canvassing for information, I put out a note to our Teme Valley Wildlife Group, to see if any of our members had come across this behaviour before. There were several interesting replies. Of note were two from two different members of the Group in two different parts of the Teme Valley. Both had found a dead, somewhat emaciated, Tawny Owl on their patch that very week. So was this an indication that the Tawny Owls were finding food hard to come by? Several people also reported that they had in times past, ‘spooked’ a Tawny Owl in their head lights from feeding on a dead road kill carcass whilst driving on the county lanes at night. And one other person wrote in to say that she used to keep ducks and on one particular occasion several years back, a small duckling had been dismembered at night. She further wrote, that she had got to know the tell tales signs of a Sparrowhawk kill, but this was something completely different. So the following evening, in a bid to find out if she had a mink or similar problem, she set up a humane trap with a dead pigeon in it. The following morning, she awoke to find the trap triggered, the pigeon pretty much devoured, and a fat and very contented looking Barn Owl sleeping off its dinner. (Which she released unharmed).

So clearly, whilst the documentation is terse, Owls will take dead carrion in the wild and it is possible that this activity is far more common than is actually recorded.

A video clip of this apparently extremely rarely seen behaviour of a Tawny Owl feeding on dead carrion taken here at Birchfield on the raptor table can be seen on the Teme Valley Wildlife Group web site www.temevalleywildlife.com. Scroll down the home page to the 2nd March 2013 and the video link will be found. You will also find some of the Buzzard videos posted above it on the 4th March.

Reference

Cramp, S (ed) 1985 The birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume 4. Oxford University Press. Section Strix aluco Tawny Owl, page 529 referring to food.

Image

Fig.1.The Raptor table. Danny Arnold

Fig.1.The Raptor table. Danny Arnold

Fig. 2. Buzzard feeding on road-kill on the raptor table. Danny Arnold.

Fig. 2. Buzzard feeding on road-kill on the raptor table. Danny Arnold.

Fig.3. Tawny Owl feeding on road-kill on the raptor table at night. Danny Arnold

Fig.3. Tawny Owl feeding on road-kill on the raptor table at night. Danny Arnold

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 15 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Invertebrate Records from Worcestershire 2012. CORRECTION Trox scaber error

John Bingham

Worcestershire Record, November, No.33, p.7. My illustration of Trox scaber[not in web page but in paper edition] was incorrect; thanks to Tony Allen of “The Coleopterist” who noticed this error. Paul Whitehead has kindly identified the beetle as being Helophorus sp. with some resemblance to the common H. obscurus. (A water beetle). My thanks to both for correcting this error, the mistake was all mine.

Image

Fig. 01. Helophorus (not Trox scaber). John Bingham

Fig. 01. Helophorus (not Trox scaber). John Bingham

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 15-16 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Observations of Formica rufa(Linnaeus, 1761) Hymenoptera, carrying another ant at Ribbesford Wood, Worcestershire

John Bingham

Whilst in Ribbesford Wood on the 2nd March 2013 I was looking at a colony of Formica rufa (wood ants) with hundreds of individuals massing on top of the nest. This behavior is quite common and typically seen in early spring with ants grouped on the outside of the nest. It is thought that they are absorbing heat from sunshine and assumedly transferring the heat energy into the nest. (Skinner 1998). Whilst I was watching the activity I noticed several ants carry back to the nest a prey item in their mandibles. It appeared to be another ant of some type and looked to be dead. I collected several of these ants and found that the ‘prey’ item was in fact another Formica rufa ant, perfectly healthy and active once released from the other ant’s mandibles.

Whilst ants constantly carry all manner of items back to the nest such as prey, twigs, leaf fragments, pine needles and seeds etc, I cannot recall seeing them carry live ants before. Possibly I have not been that observant but I am fairly certain that during the summer, despite looking at ant activities, I have never witnessed such behavior. I can find nothing about this except that ants do move and carry other ants if moving nest sites (Pontin 2005). However, in this case all the ants were returning towards the nest as if they were returning with exhausted fellow ants. The air temperature was cool, 3-4°C, so I wondered if they were getting chilled, but they were still very active once collected?

I spent an interesting 30 minutes trying to photograph the activity during which time ants carrying ants appeared every 10 seconds or so in a steady stream back to the nest. The ants were locked mandible to mandible with the gaster of the carried ant tucked tightly under the head of the other. (See photographs).

I sent an image to various people and Geoff Trevis kindly forwarded it to Mike Fox at BWARS who commented that; ‘ants do often carry one another…. photo shows the typical carrying method well. At this early date in the season it is possible that some of the workers had got chilled and become torpid and livelier ants were carrying them back to the nest where they could warm up’…. ‘Some workers spend the majority of their time doing absolutely nothing. It could be that some of these “lazy” ants were found stationary outside the nest and this prompted their nest mates to pick them up’.

This seems a plausible answer, so ants get exhausted in cold weather and need a lift back to the nest to warm-up! Unless anyone can come up with another explanation?

References

Skinner, G. J. 1998. British Wood-ants. British Wildlife 10(1):1-8

Pontin, J. 2005. Ants of Surrey Surrey Wildlife Trust.

Images

Fig. 1. Formica rufa carrying another ant. John Bingham

Fig. 1. Formica rufa carrying another ant. John Bingham

Fig. 2. Formica rufa carrying another ant. John Bingham

Fig. 2. Formica rufa carrying another ant. John Bingham

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 17 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Phleogena faginea (Fr.) Link (1833), Basidiomycota, Fungi. Fenugreek Stalkball in Shrawley Wood, Worcestershire

John Bingham

On 9th November 2012 I discovered the fungus Phleogena faginea growing out of an old decaying lime coppice stem in Shrawley Wood. The fungus was growing in short rows running up and down the coppice stem, bursting out through cracks in the bark. (Fig. 1.). The stem on which the fungus was growing was part of a large overstood lime coppice stool within heavily shaded woodland. Several of the coppice stems were decayed and the fungus was growing on one of these stems.

This is mainly a southern species with possibly only one other record from Worcestershire according to NBN Gateway. As this fungus is small and tends to fruit quite late in the season well into winter it may be overlooked. It has a distinctive shape with the round head and short stalk with a characteristic smell of fenugreek or curry especially when dry. Few popular guides on fungi include the species but Sterry (2009) does. Possible some slime moulds could be mistaken for it but the smell should be evident. Probably an over-looked species that may be common in more neglected woodland?

References

Sterry, P & Hughes, B. 2009 Collins Complete British Mushrooms and Toadstools Collins

NBN Gateway web pages

Image

Fig. 1. Phleogena faginea Shrawley Wood. John Bingham

Fig. 1. Phleogena faginea Shrawley Wood. John Bingham

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 17 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Fender Fungus Melanotus horizontalis

Arthur W. Cundall

On 17th November 2012 I was visiting the National Trust property Croome Court, at SO 887451, with my family. Immediately in front of the House an area of waste material had been cordoned off by means of a rope, supported at intervals by metal posts. My son-in law, Denis Kilner, noticed that on several of the 2 inch diameter rope catenaries there were clusters of a chestnut coloured bracket-type fungus. It was considered imprudent to collect samples, but a hasty photograph was taken. This was shown to John Meiklejohn, who was unable to suggest an identification.

Following a period of floods, during which the property was closed, a return visit was made on 29th November 2012, when the fungal growth was found to have deteriorated, though still present. Another roped off area, 1km distant at SO 886446 was found to have younger, identical growths, which were photographed under better conditions (Fig. 1.). A few samples of the stem-less fruiting bodies were collected from which a spore cast was taken and submitted to John Meiklejohn who was unable to obtain an identification. He then sent the specimens to the Mycology Department at Kew for their opinion.

The reply from Dr A Martyn Ainsworth, Senior Researcher in Fungal Conservation, stated that he had identified the fungus as Melanotus horizontalis, the usual habitat for which was wood of various sorts and dead stems such as bracken. However, there were previous British records of it living on rope, leading to the common name “Fender Fungus.” He stated that he had added the specimens to the collection at Kew as K(M)18705.

The occurrence of this uncommon fungus growing on an uncommon host is the first record for Worcestershire. The invaluable assistance provided by John Meiklejohn in obtaining an identification is acknowledged.

Reference.

Shattock, J & R. 2006. Fender Fungus. Field Mycology7 (3):79-80.

Image

Fig.1. Melanotus horizontalis. Arthur Cundall

Fig.1. Melanotus horizontalis. Arthur Cundall

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 21 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Hybrid Greenfinch x Goldfinch in Redditch

Gary Farmer

On the 15th December 2012 I noticed an odd finch feeding with Goldfinches on Teasels in my garden in Redditch. I managed to get a couple of reference pictures before it disappeared. The bird appeared to be slightly larger than the Goldfinches and lacked the bright colours, although the areas around the head and face that should have been coloured were tinted. I checked various books and websites looking for hybrid photo (either deliberate crosses with canaries etc or wildbirds) but found nothing matching. I didn’t see the bird again and thought that it had moved on.

However on the 16th April 2013 what I believe to be the same bird was spotted drinking from my bird bath, again in the company of Goldfinches. By then the red around the face was more coloured although more Robin’s breast than Goldfinch face. Also the bill appeared a little heavier than a Goldfinch; more towards Greenfinch I thought. See Figs. 1-3.

Coincidentally an article on colour aberrations in birds appeared in British Birds (van Grouw 2013) but nothing described therein matched ‘Farmer’s Funny Finch’ so I sent the picture to him for comment. My email and his reply follows:

Dear Hein van Grouw

During the winter I had an odd finch in my garden which I thought might have been a hybrid between Goldfinch and Greenfinch. It looked mostly Goldfinch but with a heavier bill.

It returned recently and having read your fascinating report in British Birds‘What colour is that bird?’ I am inclined to think that it might be a partly dilution ‘isabel’ Goldfinch. I have attached the most recent photo and should be very interested to hear your thoughts.

Kind regards

Gary Farmer

Dear Gary Farmer,

Thank you for your kind email and nice photo.

Dilution always affects the whole bird so partial dilution is not possible. This fascinating bird is indeed a hybrid and given it has green colour in places a Goldfinch should not have green (in fact Goldfinches do not have any green feathers at all), I agree with you that the other parent was most likely a Greenfinch.

This is an interesting observation as hybrids in the wild are very rare.

Best regards.

Hein

Hein van Grouw, Curator, Bird Group, Dept. of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Akeman Street, Tring, Herts, HP23 6AP, UK

Tel: +44 (0)207 942 6253 (direct) or 6158 (operator), Fax: +44 (0)207 942 6150, E-mail: h.van-grouw@nhm.ac.uk

Reference

Van Grouw, Hein. 2013. What colour is that bird? The causes and recognition of common colour aberrations in birds. British Birds 106:17-29 (January 2013).

Images

Fig. 1. Goldfinch x Greenfinch hybrid (lower) and normal Goldfinch (higher) in a Redditch garden. Gary Farmer

Fig. 2. Hybrid Goldfinch x Greenfinch. Gary Farmer

Fig. 3. Hybrid Goldfinch x Greenfinch. Gary Farmer

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 9-10 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

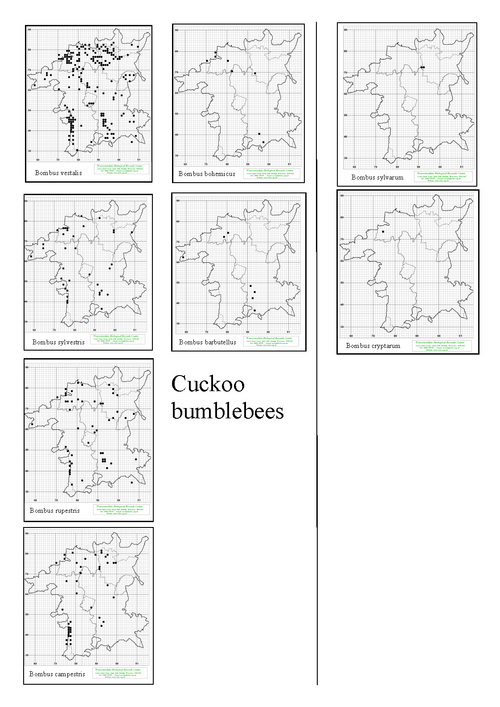

Mapping Worcestershire’s Orthoptera

Gary Farmer

To add value and interest to the proposed Orthoptera atlas we would like to gather information on behaviour of species within this group in Worcestershire. Note that besides grasshoppers and crickets this group contains earwigs and cockroaches. There are many questions to be answered including the following:

Has anyone seen a cockroach lately?

We have no native cockroach species in Worcestershire but we have records for four introduced species. The number of records for each species is however very small (one each for three species, four from the 1940s for the other) and we have no records for the 21st century. Surely we have cockroaches lurking somewhere in the county; in basements, under fridges, in warehouses or shops or have we really eradicated cockroaches from Worcestershire?

Is the Common Green Grasshopper still common in Worcestershire?

Common Green Grasshopper Ommocestus viridulus appears to be losing ground in the county. Data held at WBRC suggest that this species was once far more common than it is today; but is this the true picture or is it the result of recorder fatigue?

Certainly available information suggests the loss of this species from many areas; have we lost the flower-rich grassland habitat favoured by Common Green Grasshoppers from these areas? This is often the first species to sing, as early as June some years and it has the classic grasshopper-rattle (the one that sounds like the Grasshopper Warbler). So even if you’ve sent in records from an area in the past send any in from this year to see if the Common Green Grasshopper is still living up to its name.

When do bush-cricket nymphs first appear in the year?

Most years bush-crickets start to emerge from eggs sometime in May and, unlike their cousins the grasshoppers, they can be identified to species from the earliest stages. Grasshoppers need to pass through one or two moults before they show the characteristic patterns that separate species. Bush-crickets however are perfect adults in miniature with the characteristics required for field identification. The exception is the coneheads; Long-winged and Short-winged are both instantly recognisable as coneheads but the nymphs cannot be indentified to species level. Habitat can be used to aid identification of Short-winged Conehead but not so Long-winged Conehead. Up until a few years ago a conehead in a Worcestershire wetland would have been Short-winged but the Long-winged Conehead has now invaded this habitat since reaching the county at the end of the 20thcentury. The latter species has actually invaded all grassland habitats in most of the county whereas the Short-winged Conehead remains restricted to wetlands with abundant rushes. So a conehead nymph on a buttercup or dandelion outside of a wetland in Worcestershire will probably be Long-winged Conehead (at this point in time) (Fig.1.).

Speckled Bush-cricket nymphs are stumpy and green, covered in tiny black spots. (Figs. 2. & 3.)

Oak Bush-cricket nymphs are plain, pale green Fig. 4.(we don’t have Southern Oak Bushcricket yet).

Roesel’s Bush-cricket nymphs have the distinctive pale U shape on the sides of their pronotum and pale patches on the sides of their thorax (Fig.5.).

Dark Bush-cricket nymphs look a little like Wolf Spiders (and a lot like adult Dark Bush-crickets) Figs 6. & 7.

This year may well see a late emergence due to the cold, snowy start to the spring so get looking and record dates and locations for the nymphs.

Other questions

Do certain colour forms occur in certain parts of the county?

Do long-winged forms of Meadow Grasshopper occur at the same sites every year or is it temperature dependant?

What do our Orthoptera choose as lecking sites: cow pats, bonfire sites, large stones, large leaves etc?

Photo identification

Adult Orthoptera can be identified reliably from all but the most blurred photos. So if you have images of Grasshoppers and Crickets in the county with a date and location I’d be happy to identify them or confirm identification. Send images to vc37hopper@gmx.com together with information on your record (date, place, grid reference, and your contact details) and I’ll let you know what you’ve photographed (if it is an Orthopteran) and add the records to the WBRC database.

Worcestershire Orthoptera web site

This spring I published a new web site dedicated to the Orthoptera and allied insects of Worcestershire. It has up-to-date distribution maps, identification tips and a full annotated list of species recorded in the county.

The site can be found at http://worcestershireorthoptera.weebly.com

Images

Fig. 1. Conehead on buttercup. Gary Farmer

Fig. 1. Conehead on buttercup. Gary Farmer

Fig. 2. Speckled Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 2. Speckled Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 3. First instar Speckled Bush-cricket with ant, Myrmica sp. Gary Farmer

Fig. 3. First instar Speckled Bush-cricket with ant, Myrmica sp. Gary Farmer

Fig. 4. Oak Bush-cricket nymph. Rosemary Winnall

Fig. 4. Oak Bush-cricket nymph. Rosemary Winnall

Fig. 5. Roesel’s Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 5. Roesel’s Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 6. Dark Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 6. Dark Bush-cricket nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 7. Dark Bush-cricket first instar nymph. Gary Farmer

Fig. 7. Dark Bush-cricket first instar nymph. Gary Farmer

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 18 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Pear leaf gall Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper

Harry Green & James Wade

Pear leaf gall (Fig. 1.), caused by Gymnosporangium sabinae, was first reported in Worcestershire around 2005 (Green 2006, Green 2007, Umpelby 2007). At the time Green (2006)) wrote as follows:

“The disease is caused by the rust fungus Gymnosporangium sabinae (= G. fuscum), which requires two hosts, pear and juniper, to complete its life cycle. Spores produced from the fungal growths on pears are airborne and infect junipers; spores produced from the fungus-induced swellings on juniper stems are airborne, travelling up to 6km, then re-infect pears. The life cycles of Rust fungi are complex. A useful description is given by Spooner & Roberts (2005)”. The alternate host is apparently Juniperus sabina, an evergreen garden shrub sometimes called Buffalo Juniper, which grows to around 3 m in height and two metres across although other juniper species may be used.

Since 2005 the leaf gall has often been noticed on pear leaves throughout the Worcestershire varying in abundance from year to year. In March 2013 James Wade sent me (HG) photographs of the fungus on the alternate host, a garden juniper, taken in April 2012 near Hanley Swan (SO8043), Figs. 2 & 3, with the comment that they showed both the fungus fruiting bodies and the strange cankers or swellings that they leave behind. This is apparently the first record of Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper in Worcestershire.

The gall on pear is reported to occur on fruit as well as leaves although the former has not been reported in Worcestershire. We should be glad to see pictures of the gall on fruit and also to receive further records from juniper. It would be helpful if the species of juniper could be identified.

References

Green, H. 2006, Pear leaf gall caused by the rust fungus Gymnosporangium sabinae. Worcestershire Record. 21:49.

Green, H. 2007. Pear leaf gall caused by the rust fungus Gymnosporangium sabinae Worcestershire Record. 22:33

Spooner, B. & Roberts, P. 2005. Fungi. Harper Collins New Naturalist Library number 96

Umpelby, R. 2007. Pear Rust. Worcestershire Record. 22:34

Images

Fig.1. Gymnosporangium sabinae on pear leaves. Rosemary Winnall

Fig.1. Gymnosporangium sabinae on pear leaves. Rosemary Winnall

Fig. 2. Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper. James Wade

Fig. 2. Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper. James Wade

Fig. 3. Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper. James Wade

Fig. 3. Gymnosporangium sabinae on juniper. James Wade

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 25-27 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

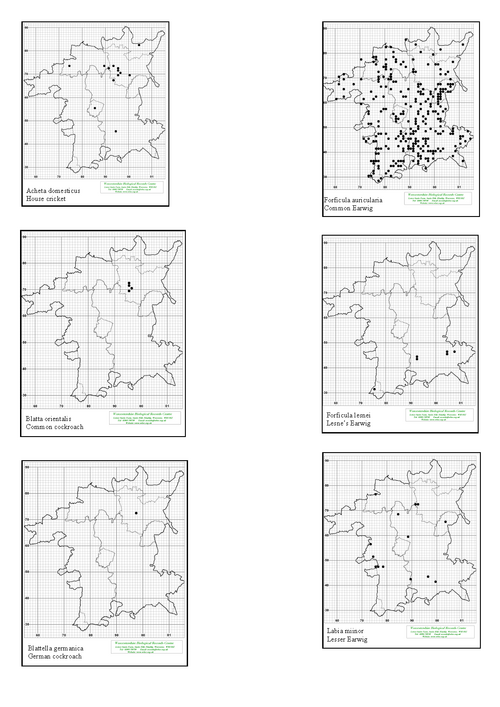

BTO Breeding Nightingale Survey 2012

Harry Green

BTO Worcestershire Regional Representative

In 2012 BTO organised national Nightingale survey, following on from previous surveys during the last 40 years. The 2012 survey aimed to investigate distribution and population change; habitat associations; and the proportion of males that are paired. The earlier surveys aimed for complete national coverage whereas the 2012 survey was based on tetrads pre-selected by BTO.

The Nightingale is a declining summer immigrant to Britain which is at the north-western edge of its range. Worcestershire is now on the very edge of that range and the distribution here has retracted to the southern parts of the county in the last forty years, although occasional birds turn up elsewhere. Numbers are now low. This means that records from Worcestershire are particularly useful in following future changes.

The 2012 survey was based on tetrads where Nightingales had been recorded during the previous ten years, and in the 1999 survey, as well as additional sites occupied since 2007 and identified from County Bird Reports, BTO Atlases, BirdTrack records, and local knowledge

The survey

The Basic survey was made between 27th April & 14th May 2012 and involved two early morning visits (between one hour before sunrise and 0830hrs). There was also an Optional Nocturnal Survey made between 18th May & 4th June to help determine the number of paired/unpaired males, and ideally this involved two nocturnal visits (between midnight and 0300hrs). This part of the survey was based on the fact that Nightingale males tend to stop singing when they find a mate and start to nest. Unpaired males sing on into the summer.

First survey period: 27th April to 14th May

1. two daytime visits to every priority tetrad

2. two daytime visits to as many non-priority tetrads as possible

3. additional daytime visits welcome, to any tetrad.

Second survey period: 18th May to 4th June

1. two nocturnal visits to as many occupied priority tetrads as possible

2. two nocturnal visits to as many occupied non-priority tetrads as possible

3. additional daytime or nocturnal visits welcome, to any tetrad

Results

Although the survey was based firmly on designated tetrad coverage other records were provided by several observers. The summary in table 1 shows all these records. Some additional records may have been submitted to BTO via BirdTrack. The BTO Report on the survey has not yet been prepared but when it is the final figures may be slightly different from those shown in table 1..

Most of the tetrads selected for the 2012 survey were covered by surveyors. However, a serious problem was caused by the awful wet and cold weather during the survey period. This made surveying and recording difficult for observers, especially those relying on evenings or weekends for surveying, and it also suppressed Nightingale song. Nocturnal visits designed to check whether males were paired on not were particularly difficult.

| Tetrad | 10 km square | Tetrad type in survey | Tetrad allocated

Yes or no |

Total or not done (nd). | Casual records | Likely tetrad total |

| SO66D | SO66 | Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO74H | SO74 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO74U | SO74 | Priority | n | nd | ||

| SO74W | SO74 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO74X | SO74 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO74Z | SO74 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO75C | SO75 | Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO75N | SO75 | Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO76K | SO76 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO76R | SO76 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO77V | SO77 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO83H | SO83 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO83T | SO83 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 2+5 | 7 |

| SO83Z | SO83 | Non Priority | no | nd | 4 | 4 |

| SO83L | SO83 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO83V | SO83 | Non priority | y | 0 | 0 | |

| SO83W | SO83 | Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO83X | SO83 | Priority | yes | 1 | 1 | |

| SO84F | SO83 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84K | SO83 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84L | SO84 | Non Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO84R | SO84 | Non Priority | yes | 1 | 1 | |

| SO84S | SO84 | Non Priority | y | 1 | 1+1 | 3 |

| SO84V | SO84 | Non Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO84X | SO84 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| SO84Y | SO84 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84B | SO84 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84J | SO84 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84T | SO84 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO84W | SO84 | Priority | yes | 5 | 1+4+1 | 6 |

| SO86A | SO86 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO86D | SO86 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO87B | SO87 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO93E | SO93 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO94A | SO94 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO94E | SO94 | Non Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO94S | SO94 | Non Priority | no | nd | ||

| SO94D | SO94 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO96I | SO96 | Non Priority | no | nd | ||

| SP04U | SP04 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SP06Y | SP06 | Priority | yes | 0 | 0 | |

| SO83P | SO83 | Casual records | 1 | 1 | ||

| SO85L | SO85 | Casual records | 1 | 1 | ||

| SO84N | SO84 | Casual records | 2 | 2 | ||

| Totals | 8 | 28 best estimate overall |

Table 1. Shows the list of tetrads in the survey and the results. There are also records from three tetrads that were not selected for the survey.

Table 2 shows the number of singing male nightingales counted in previous surveys compared with the 2012 survey. The figures for 1998 are from a local survey (not part of a national survey). Otherwise 1976, 1980, 1999 and 2012 were all BTO National Surveys. The column designated “1999 plus later casual records so a guess at likely count if no change. Tetrads selected from this list formed 2012 survey sites” suggests the totals that might have been expected in the 2012 survey if there had been no changes in population or distribution. The ‘estimated guess’ was about 60 singing males. In fact in 2012 only 28 singing males were recorded. There may have been unreported males elsewhere in the county, and the bad weather may have led to under-recording. However it seems likely that the Worcestershire Nightingale population has continued to decrease and birds are now only found in relatively small areas in the south of the county with occasional solitary birds singing elsewhere. It will be interesting to see the results of the full national survey.

BTO surveys and other data show a slow decline in the distribution of Nightingales in England extending over many years with a slower reduction in overall numbers. Likely causes are pressures on migration and in winter quarters, perhaps compounded by habitat loss in Britain such as disappearance of over-grown hedges, scrubby places and woodland coppice management. The increasing numbers of deer are also reducing habitat quality and cold wet springs may be reducing nesting success. This is a summary from http://blx1.bto.org/birdtrends/species.jsp?s=nigal&year=2012 where there are many references to publications.

The provisional results and maps for the new BTO Atlas show a staggering national loss between 1995 and 2008 of 53%.

A series of reports for Worcestershire have been published in Worcestershire Record perhaps most easily found by visiting the web site www.wbrc.ork.uk and searching Worcestershire Record for Nightingale.

In view of the changes in Worcestershire it will be well worth recording nightingales every year in the future. Please enter your records on BirdTrack or send them to Worcestershire County Bird Recorder, or send them to me. Please remember Nightingales are now scarce birds so please take care not to cause disturbance to the birds or damage to habitat when they are found.

| 10×10 km squares (or part thereof) forming BTO Worcestershire | 1976

BTO survey |

1980

BTO Survey |

1998

Local survey |

1999

BTO survey |

1999 plus later casual records so a guess at likely count if no change. Tetrads selected from this list formed 2012 survey sites | 2012

Sample tetrad survey plus allocated tetrads. Squares designated by a dash indicates no tetrad surveyed |

| SO 56 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | – | |

| SO 66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

| SO 73 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 1 | – |

| SO 74 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 0 |

| SO 75 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| SO 76 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| SO 77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SO 83 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 13 |

| SO 84 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 16 | 17 | 14 |

| SO 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SO 86 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| SO 87 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| SO 93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| SO 94 | 10 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| SO 95 | 50 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| SO 96 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| SO 97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| SP 03 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 0 | – |

| SP 04 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SP 05 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| SP 06 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| SP 07 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| SP 13 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| SP 14 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Totals | 88 | 70 | 42 | 59 | 63 | 28 |

| BTO survey report totals. | 92 | 66 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Table 2. Numbers of Nightingales recorded in 10×10 km squares during the BTO 1976 and 1980 surveys; reported in 1998 (local survey); recorded in 1999 BTO survey; and reported during the 2012 sample survey. The national survey report totals in 1976 and 1980 differ from the county totals because some records were probably sent directly to BTO and there was confusion over boundaries between Herefordshire and Worcestershire

Acknowledgements

Very many thanks to all who counted, or attempted to count, singing Nightingales in 2012 for the BTO Survey and to birdwatchers who provided additional records, especially Rob Prudden who gathered records from several sources.

Images

01. BTO

01. BTO

02. Nightingale. Ray Bishop

02. Nightingale. Ray Bishop

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 4-8 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

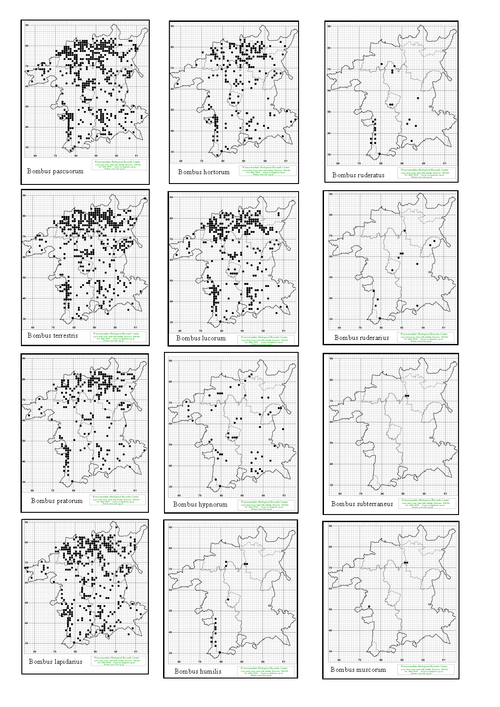

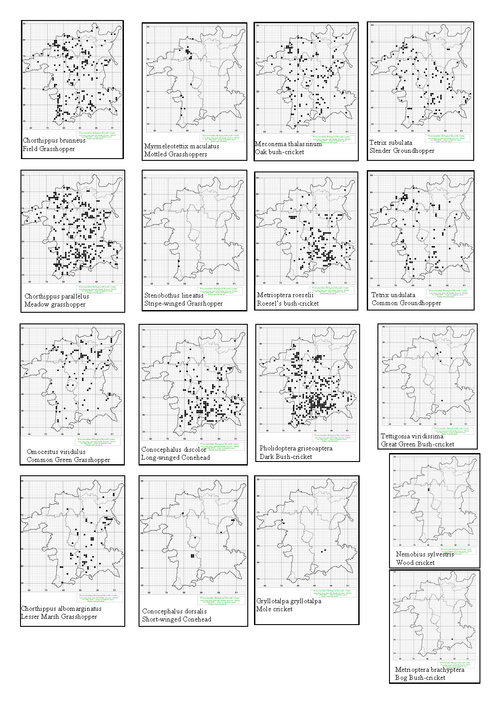

Bumblebees and Orthoptera: Two new atlases

Harry Green

Worcestershire Recorders, working closely with Worcestershire Biological Records Centre (WBRC) aim to produce two illustrated county ‘Atlases’: ‘Bumblebees’ and ‘Orthoptera’ in the near future. To do this we need records so please help!

One of the main reasons for preparing these Atlases is because the national distributions of several species are changing either through new invasions or declines and these appear to be particularly noticeable in Worcestershire. Many bumblebee species are in severe decline apparently mainly due to intensive agriculture. However Britain and latterly Worcestershire has been invaded by Bombus hypnorum, the Tree Bumblebee, which has moved in from Europe. Amongst crickets two species of bush-crickets Conocephalus discolor , the Long-winged Conehead, and Metrioptera roeselii, Roesel’s Bush-cricket, have invaded the county within the last 12 years and they are still spreading westwards. Additionally very little has been published on these two groups in Worcestershire.

By February 2013 the WBRC database contained 3795 Orthoptera records and 4103 bumblebee records for Greater Worcestershire. These records are the base on which we can build further work, especially in 2013, by collecting as many new records as possible from all parts of Worcestershire. The aim is to produce illustrated accounts for all the species in these two groups that occur in the county. Each species account will probably contain a distribution map (hence ‘Atlas’), colour illustrations of the species, and a review of its natural history and status including any Worcestershire historical information that can be found.

A glance at the preliminary maps shows large holes in the distribution of many common species (Figs. 1-4 prepared by WBRC). Many of these holes are there simply because nobody has made records for those areas. Please try and visit such areas and make records. The success of these Atlases will depend on the enthusiasm recorders have for collecting new records in 2013.

Obtaining records of cockroaches (see Gary Farmer’s article) and for the two earwigs other than the common species presents a challenge. Farm manure heaps are supposed to be good for the Lesser Earwig and Lesne’s Earwig may be restricted to SE Worcestershire where it appears to inhabit Old-Man’s-Beard (Farmer 2012).

Some species in both groups are quite easy to identify, others are more difficult. Fortunately there are helpful modern guides to identification and good keys are included in recent volumes of Collins ‘New Naturalist’ series – see references.

Many people now use digital cameras to photograph insects and many of these Atlas species (but not all!) can with care be identified from pictures. For orthoptera Gary Farmer is offering an identification service – see his article on this Worcestershire Record. Most common species of bumblebees are fairly easy to identify but problems arise from differences between sexes and the worn bleached colours apparent as the bees get older, especially workers. The latter can also vary greatly in size. We can offer some help with photo identification of bumblebees although they are quite difficult to photograph showing identification features clearly. Pictures should in the first instance be sent to records@wbrc.org.uk. They will only be considered if they are accompanied by your name, date the bumblebee was seen, and location including grid reference (these can easily be determined from maps or the web site http://wtp2.appspot.com/wheresthepath.htm.

Receipt of pictures will be acknowledged hopefully with confirmation of identification. Records from these will be send to the WBRC database by us and you do not need to re-send them.

How to send in records.

Records should be sent to WBRC. They can be either as written documents posted to WBRC, Lower Smite Farm, Hindlip, Worcester, WR3 8SZ or by email to records@wbrc.org.uk. Please make sure your name and contact details are included. It is best to send records by email attachment if possible. The attachments can either be simple written documents but if you are sending a batch of records please, if possible, use the spreadsheet which can be down-loaded from the web site http://wbrc.org.uk/. On the front page click on An expanded Excel sheet for your records and on the next page click on An expanded Excel sheet can be found here and a spread sheet will automatically be downloaded to your computer. This can be saved and then used to send batches of records (you are advised to keep a copy of each batch).

References and guides to identification

Orthoptera

A useful guide is A photographic guide to Grasshoppers & Crickets of Britain & Ireland by Martin Evans & Roger Edmondson published in 2007 by WGUK. ISBN 978-0-9549506-1-3.

The older standard book which also contains cockroaches and earwigs is Grasshoppers and allied insects of Great Britain and Ireland by Judith A. Marshall & E. C. M. Haes published on 1988 by Harley Books. ISBN 0 946589 13 5.

There is a good key in Grasshoppers & Crickets by Ted Benton, volume 120 in Collins New Naturalist series published in 2012. The book also contains many good photographs and a wealth of useful information..

Farmer. G. 2012. Lesne’s Earwig Forficula lesnei. Scarce in Worcestershire or just overlooked? Worcestershire Record 33:24.

Bumblebees

The most useful guide is Field Guide to the Bumblebees of Great Britain & Ireland by Mike Edwards & Martin Jenner. First published by Ocelli in 2005, revised edition 2009. ISBN 9780954971311.

There is a good key in Bumblebees by Ted Bention, volume 98 in the Collins New Naturalist series published in 2006. The book also contains many good photographs and a wealth of useful information.

A great deal of useful information can be found on the Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society (BWARS) web site including a download Bees in Britain, see: http://www.bwars.com

The WBRC web site www.wbrc.org.uk contains all but the most recent contents of past Worcestershire Record and these include many notes and papers on bumblebees and orthoptera.

For both groups there are many images to be found through internet searches and these can be very helpful but take care as the identifications are not always correct.

Images

Fig. 1. Bumblebee distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 1. Bumblebee distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 2. Bumblebee distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 2. Bumblebee distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 3. Orthoptera distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 3. Orthoptera distribution maps February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 4. Orthoptera distribution map earwigs & cockroaches February 2013.WBRC

Fig. 4. Orthoptera distribution map earwigs & cockroaches February 2013.WBRC

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 19 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Rainfall at Old Storridge 2012

Garth Lowe

It is called the (naughty) Jet Stream! Between March and April 2012 it finally shifted after being in the same place over us for around 18 months, giving us a very much drier period, shown by the rainfall in 2011. It then stayed in its new position for nine months and has given us quite the opposite effect: the disastrous summer of 2012. The shift is obvious from the monthly figures below! (Table 1.)

In my report for last year I said how ironic it was to get a record dry year after 50 years of recording rainfall, now it is just the opposite. To my utter astonishment on totaling up for the year, and for the first time ever in over 50 years recording rainfall, the figure went over the magical figure of 1000mm or 40 inches, and ended up at 1091.5 mm or 43 inches. Another way to look at it is: well over 3 feet of rain! That must be hopefully the last bad record I have to submit in an annual report.

The wettest day of the year was September23rd, when 73.5mm fell, just under 3 ins. There were also two other wet spells in the middle of June and July, when 45.5 and 42.5mm fell over two three day periods. Once it started raining in April there were only two reasonable spells with no rain, nine days from 20th July and eight days from 1st September! One small fact to be thankful for is that the Leigh Brook only broke its banks on one occasion, on the morning of November 24th, when after an overnight fall of 38.8mm, the cars of Old Storridge cul-de-sac, were isolated for a few hours!

Looking back at the records it is obvious these wetter years didn’t kick in till 2000, when over 900mm was logged and since then there have now been two more, whereas from 1962 to 1999 there were none! Another fact about 2012 is that there were six months when over a 100mm, or more than 4ins, fell. The last new record to mention is the average monthly rainfall for 2012 which finished up at 91mm, an all time record for this long rainfall record. In 2000, another wet year, the average was 81.5mm.

| Year(s) | JAN | FEB | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEP | OCT | NOV | DEC | TOTAL |

| 2011 | 43.3 | 54.6 | 13.2 | 2.0 | 58.4 | 42.5 | 31.8 | 29.1 | 35.5 | 35.7 | 60.9 | 64.4 | 471.1 |

| 2012 | 34.0 | 25.0 | 12.8 | 131.8 | 53.5 | 207.5 | 111.3 | 81.8 | 101.6 | 80.2 | 122.3 | 130.3 | 1091.5 |

| 40 year. monthly average 1962-2007 | 67.9 | 50.5 | 55.3 | 55.5 | 59.6 | 56.1 | 49.6 | 63.5 | 63.6 | 70.5 | 65.8 | 74.4 | 732.3 |

| 1916-1950 average. From Malvern Free Library | 74.9 | 51.6 | 48.5 | 54.9 | 64.5 | 46.5 | 66.3 | 67.6 | 61.2 | 71.9 | 73.2 | 68.3 | 749.3 |

Table 1. Rainfall (in mms.) during 2011 and 2012 recorded at Old Storridge compared with historic records. Note that 25.4mm = 1 inch.

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 19 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 19-20 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Ectoparasite Polysphincta sp., Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae, of the spider Araniella sp. found at Feckenham Wylde Moor

Paul Meers, Brett Westwood & Harry Green.

The three authors all played a part in the account set out below, with Harry Green writing the script. Those who know about spider ectoparasites may be mildly amused at our ignorance and sudden enthusiasm but as most readers will probably know nothing of them it seems worth telling the ‘story’.

On the 8th May 2013 I received an email from Paul Meers, volunteer manager at the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust’s Feckenham Wylde Moor Reserve, with a picture (Figs. 1 & 2.) taken that day at the reserve. He wrote that he had never seen anything like it before and could we identify the larva; was it a parasite on the spider; and could we identify the spider; mentioning that it was about 3 mm long. I didn’t know the answers to these questions so circulated the picture to naturalist colleagues. Fortunately the picture triggered Brett Westwood’s memory and he wrote: “Excellent picture of spider and parasite. I think the spider is most likely to be Araniella cucurbitina which is the commonest small green spider at this time of year. The larva attached to it is probably an ichneumonid wasp – the wasps of the genus Polysphincta lay eggs on araneid spiders (orb weavers) and the wasp grubs live as ectoparasites on the adult spiders.” He backed this up by referring us to British Insects (Barnard 2011) page 254 and Foelix (1996). The latter writes “Members of the wasp family Ichneumonidae also plague spiders. They attach their eggs to the spider’s body or deposit them in the spider’s egg-sacs. Polysphincta raids orb weavers and fastens its eggs to their abdomens. The larva lives as an ectoparasite on the spider’s body, ingesting its body fluid (Nielsen, 1923, 1932)”.

At this point I became hooked and set about finding out more about these parasites. The first internet search came up with

http://www.pbase.com/holopain/image/64823442

http://spiders.entomology.wisc.edu/pred_para/ectoparasite/index.html

which show some remarkable pictures of the parasites attached to spiders.

Later I found a variety of papers (for example Schmitt et al 2012), and pictures from across the world, some of the latter very similar to Paul’s original. From the British viewpoint the following are examples:

http://hedgerowmobile.com/Polysphincta.html

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hedgerowmobile/494043879/

http://www.wildaboutbritain.co.uk/forums/insects-and-invertebrates/67983-ichneumon-larvae.html

I then turned to the books immediately available to me. Bristowe (1958) in his New Naturalist volume The World of Spiders writes “Spiders of many families can be found, especially in spring and early summer, with a white larva attached to the upper side of their abdomen. The larva has hatched from an egg laid by a Pimpline ichneumon which first temporarily paralyzes the spider with its sting in order to do this. Like the old man of the sea, it cannot be dislodged and for weeks the spider feeds as usual whilst the larva grows and finally kills her”. Leading back in time from this I consulted Bristowe (1939) The Comity of Spiders which contains a chapter on “The enemies of spiders”. The section headed Ichneumonidae begins “In spring and in the later summer months a pale larva is often seen attached to the backs of small spiders. Keep these spiders in captivity and it will be found that they spin webs, catch flies, mate and perhaps even lay eggs as though there was no parasite sucking their juices.” He then goes on to describe how eventually the larva kills the spider and moves to its web where it spins a cocoon and pupates. Within a week or so a Pimpline ichneumonid emerges, the commonest species probably Polysphincta tuberosa.

While consulting this mixture of ancient and modern I found that frequently quoted sources were Neilsen’s work in Denmark (1923, 1932) and Fitton et al (1987), The hymenoptera associated with spiders in Europe, neither of which were easily available via the internet. The second author of the last paper is Mark Shaw and as I had noticed many papers of his on hymenoptera parasitica in various entomological journals I emailed Paul’s picture to him asking if he could comment and perhaps send me a reprint of the paper. His response was quick and very helpful and brought nine useful papers and information on how to find rear and identify many species. He wrote “The ectoparasitoid in your picture is undoubtedly a Polysphincta species, almost certainly the common P. tuberosa (which parasitises Araniella spp, Araneus diadematus and Zygiella) … but if you are lucky it could be the rare P. boops which (although larger!) seems to be restricted to just Araniella (possibly one or more of the rare ones)”.

This note will, we hope, encourage readers to look at spiders more closely for these ectoparasites. Mark Shaw also encourages us to search for parasitoids of spiders other invertebrates. He would be very happy to receive specimens and has sent several notes and papers on finding and rearing them. One useful publication is Rearing parasitic hymenoptera(Shaw 1997) written for the Amateur Entomologists’ Society from which it may be purchased. Another is Rearing parasitic wasps from spiders and their egg sacs (Shaw 1990) originally published in the British Arachnological Society’s members’ Handbook. I have some of the notes available as pdf files.

References and short bibliography.

Barnard, P.C. 2011. The Royal Entomological Society Book of British Insects. Wiley-Blackwell

Bristowe, W.S. 1941 The Comity of Spiders. Volume 2. The Ray Society; London

Bristowe, W.S. 1958. The World of Spiders. Collins New Naturalist: London

Fitton, M.G., Shaw, M.R., & Austin, A.D. 1987. The Hymenoptera associated with spiders in Europe. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 90:65-93. Article first published online: 15 May 2008 DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1987.tb01348.x

Fitton, M.G., Shaw, M.R., & Gauld, I.D. 1988. Pimpline ichneumon-flies Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Pimplinae. Handbooks for the identification of British Insects. Volume 7, part 1. Royal Entomological Society. Out of print but available as free download from RES web site.

Foelix, R.F. 1996. Biology of spiders. Oxford University Press.

Nielsen, E. 1923. Contributions to the life history of the pimpline spider parasites (Polspincta, Zaglyptus, Tromatobia) (Hym. Icheum) Entomologiske Meddelelser. 14:137-205.

Nielsen, E. 1932. The biology of spiders. Volume 1 in English, summarising Volume 2 in Danish. Lewin & Munksgaard. Copenhagen.

Schmitt, M., Richter, D., Göbel, D & Zwakhals, K. 2012. Beobachtungen zur Parasitierung von Radnetzspinnen (Araneidae) durch Polysphincta rufipes (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). Arachnologische Mitteilungen. 44: 1-6 Nürnberg, Dezember 2012

Shaw, M.R. 1996. Rearing parasitic wasps from spiders and their egg sacs. British Arachnological Society’s members’ Handbook

Shaw, M.R. 1997. Rearing parasitic hymenoptera. Amateur Entomologists’ Society.

Images

Fig. 1. Spider Araniella with ectoparasite Polysphincta. Paul Meers

Fig. 1. Spider Araniella with ectoparasite Polysphincta. Paul Meers

Fig. 2. Spider Araniella with ectoparasite Polysphincta. Paul Meers

Fig. 2. Spider Araniella with ectoparasite Polysphincta. Paul Meers

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 23-24 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Birds in Worcestershire – October 2012 to March 2013

by Gavin Peplow

A rather cold and wet winter continued right the way through to a very cold March, dominated by easterly winds and leading to one of the latest springs for many years.

October began with the Great White Egret remaining at Grimley, feeding along the extensive shoreline along with up to three Little Egrets. Waterfowl were represented by four Common Scoter at Bittell, a singleton at Upton Warren – all mid month, whilst a Scaup also visited this last site and four Red-crested Pochard found plenty to feed on at Kemerton Lakes. A very late Honey Buzzard was reported over Stourport during the third week, whilst more expected were up to three Short-eared Owls on Bredon Hill. Three individual Rock Pipits passed through Ripple Pits and a Water Pipit was reported briefly at Upton Warren. Up to five Ring Ouzels were counted on Bredon Hill and a few were seen on the Malverns. Typically late migrants, Black Redstarts were seen briefly at Lower Park Farm, Tardebigge and Bredon Hill, whilst other scarce passerines included four Hawfinches at Coney Meadows – an exciting new local reedbed reserve near Salwarpe; along with scattered Crossbill records at various sites including a flock of at least 40 at Eymore Wood.

November began with the first Waxwing of what was to become an impressive influx over the first part of the winter, this in spite of the berry crop being rather limited and quickly devoured by other migrants such as Fieldfares and Redwings! Dark-bellied Brent Geese were found at Bredon’s Hardwick and Ripple and an impressive flock of 52 Pink-footed Geese flew over Tardebigge at the beginning of the month. First one and then two Long-tailed Ducks arrived at Bittell and stayed for several weeks, being understandably popular as a species that is only seen every three or four years on average in the County. Scaup were found at Clifton Pits and Hewell Grange whilst a Little Gull loitered at Kemerton Lakes for a couple of weeks. This time of year typically witnesses a small passage of Snow Buntings on the Malverns and this autumn was no exception with three birds being seen in the first and third weeks. A Black Redstart at Ripple was a welcome addition to the site list, particularly as it was also one of very few seen during the year. Other passerines included a count of 60 Corn Buntings at Summerfield – a pretty exceptional number these days. A near adult Glaucous Gull arrived at Lower Moor at the end of the month and was earlier than most records, obligingly remaining well into December.

Waxwing numbers peaked at the beginning of December, with the largest flocks being 54 in Evesham and 53 at Webb’s Garden Centre, Wychbold. Four Snow Buntings, again on Worcestershire Beacon during the second week were likely to have been new arrivals, whilst a little further south only three Hawfinches could be found at their traditional haunt on the flanks of Chase End Hill. Three Whooper Swans at Ripple were a sure sign that winter had arrived and a redhead Smew at the same time was again a first for the locality. The year concluded with an unseasonal Little Egret at Westwood and a ringtail Hen Harrier drifted through Kemerton Lakes

2013 started wet with the river valleys being flooded and good counts of wildfowl being reported at the traditional floodplain sites. The three adult Whooper Swans returned to Ripple mid-month, whilst further adults were seen at Grimley and Lower Moor. Two adult Bewick’s Swans at this first site quickly moved north and were seen a bit later at Clifton Pit, whilst a drake Scaup also took up residence at Ripple, eventually remaining right through to April. Lower Moor also hosted an Iceland Gull, though it was often difficult to find amongst the many thousands of Gulls loitering in the area. Grimley ran into a purple patch from the third week during a cold spell, attracting two redhead Smew, Grey Plover, Sanderling, Short-eared Owl and at least 20 Brambling, but the undoubted highlight was a party of no less than seven Common Cranes that were seen over a period of six days around Clifton Pits – an unprecedented record for the County, with all birds being unringed / untagged and so apparently not part of any of the south-western reintroduction schemes! Elsewhere two ‘Siberian type’ Chiffchaffs – birds from one of the north-eastern populations at least – were found at Powick Sewage Works, whilst the four Snow Buntings were seen again on several dates around the north Malverns. Perhaps the same ringtail Hen Harrier from December was seen on the south side of Bredon Hill and then later reported around the Overbury Estate, whilst a Knot at Ripple was again new for the site.

February dawned with a first winter Great Northern Diver being found at Westwood Pool. It lingered overnight but was soon off the following morning – the first record for four years in the County. A further two Whooper Swans dropped in to Upton Warren briefly in what was a very good winter for the species, whilst two Common Scoter also paused briefly there. Elsewhere a splendid drake Smew lingered at Bittell, whilst the two redheads remained faithful to Grimley. A Spotted Redshank at Ripple was not only exceptional for the time of year, but also yet another first record for the site! Gulls normally dominate many of the bird records in winter and this year was no exception. Four or five Iceland Gulls were found, whilst the trickier to identify Caspian Gull was confirmed on a couple of occasions near Wyre Piddle. A handful of Mediterranean Gulls were seen including two birds roosting on the floodwater on Upton-upon-Severn mid month. Black-tailed Godwits were found at Upton Warren and Lower Moor during the last week and several Red Kites were seen at scattered locations.

After only one Bittern had been seen at Upton Warren for much of the winter, three birds congregated there for a couple of nights in mid March whilst another was watched at Coney Meadow on and off. Passage Avocets were seen at Bittell and Ripple, whilst numbers built up to 16 at Upton Warren later in the month. Yet another Common Crane was reported, this time a single bird flying over Arley and a Short-eared Owl showed intermittently at Lower Moor.

It’s been one of the best springs for a good number of years for passage Kittiwakes with a good sprinkling of sightings from around the County. Early returning migrants included a Marsh Harrier at Upton Warren, Ospreys at Ripple and Grimley and a Ring Ouzel at Clifton Pits, though the bitterly cold winds that prevailed at this time held back almost all summer visitors, including species such as Sand Martin and Wheatear, well beyond their normal return dates!

For information on recent sightings and to report any unusual birds you may see, please visit http://www.birdingtodaynews.co.uk

Images

Fig. 1. Waxwing at Upper Moor 5th January 2013. Andy Warr

Fig. 1. Waxwing at Upper Moor 5th January 2013. Andy Warr

Fig. 2. Common Cranes, Ripple 20th January 2013. Andy Warr

Fig. 2. Common Cranes, Ripple 20th January 2013. Andy Warr

Fig. 3. Whooper Swans, Ripple, 9th December 2012. Andy Warr

Fig. 3. Whooper Swans, Ripple, 9th December 2012. Andy Warr

Fig. 4. Knot at Ripple 26th January 2013. Andy Warr

Fig. 4. Knot at Ripple 26th January 2013. Andy Warr

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 37-39 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Vascular Plant Records 2012

Bert Reid

General comments

In my article on Vascular Plant Record 2010 and 2011 (Worcestershire Record number 31, November 2011) I explained how local botanical recording had declined after the end of organised field work for the Worcestershire Flora Project. I made some suggestions about how we might reinvigorate plant recording through an e-mail group, but this idea received very little interest. We are still heavily reliant on a handful of stalwarts who provide the vast bulk of new records, so if anyone else can help, please e-mail me at bert_reid@talk21.com.

The Botanical Society for Britain & Ireland – theB.S.B.I.

The BSBI is the major national society for the study of vascular plants. It organises plant recording by vice-county, with our area (VC 37) looked after by joint recorders John Day and Bert Reid. The Worcester Flora Project covers a slightly different area with all of VC 37 plus the small areas of modern Worcestershire within neighbouring vice-counties. The BSBI runs many projects and details of these can be seen on their website (http://www.bsbi.org.uk/). One project is of particularly importance to our Worcestershire recording.

Maps Scheme.

The Maps Scheme tries to plot the distribution of all taxa at hectad and/or tetrad level. The maps generated show different date classes with the recent class being 2010 to 2019, so we now three years in to the class. It is vital that we get as much information as possible in for the creation of Atlas 2020 at the end of the date class. We would like to receive any records for VC 37, ideally at 1x1km square level or closer. As always we need information of taxon, site, grid reference, date, recorder name, and comment where appropriate.

Table 1 shows the progress so far at hectad level for date class 2010-2019. It is incomplete, since not all records have yet been entered up, but it gives a reasonable overall picture.

The total of 14283 compares with the previous date class (2000-2009) total of 21823. We are therefore over 65% of a reasonable total. Additions in 2012 totaled 3310, with 535 in SP13, 258 in SO76, 256 in SP03, 255 in SO72, 250 in SO86, 233 in SP14, 157 in SP04, and 152 in SO88.

The main contributors to the maps scheme in the year were John Day, Bert Reid, Keith Barnett and Anne Daly plus many people on various field meetings.

| Hectad | Taxa | Hectad | Taxa | |

| SO56 | 216 | SO93 | 391 | |

| SO64 | 98 | SO94 | 886 | |

| SO65 | 145 | SO95 | 777 | |

| SO66 | 373 | SO96 | 912 | |

| SO67 | 110 | SO97 | 381 | |

| SO72 | 255 | SO98 | 288 | |

| SO73 | 567 | SO99 | 0 | |

| SO74 | 698 | SP03 | 393 | |

| SO75 | 260 | SP04 | 533 | |

| SO76 | 429 | SP05 | 324 | |

| SO77 | 503 | SP06 | 421 | |

| SO78 | 187 | SP07 | 204 | |

| SO82 | 5 | SP08 | 175 | |

| SO83 | 446 | SP13 | 536 | |

| SO84 | 649 | SP14 | 234 | |

| SO85 | 556 | SP15 | 0 | |

| SO86 | 649 | SP16 | 195 | |

| SO87 | 640 | SP17 | 172 | |

| SO88 | 471 | SP18 | 204 | |

| TOTAL | 14283 |

Table 1 shows the progress so far in collecting records at hectad level for date class 2010-2019.

Important & Interesting Records – 2012

2012 was an interesting and unusual year for plant recording in the county. 12,885 records from 28 recorders reached the database: on the face of it this appears a healthy situation but the figures mask the reality. 6 of the recorders noted only single records with another 7 in single figure. Most of the other recorders only appear on the database in conjunction with John Day and others on various field meetings, and their records reached the database because John collated and submitted them. In truth, fewer than 10 people are actively recording plants and ensuring their entry. The top four recorders are responsible for 85% of the records.

The year had a bumper crop of rare and interesting plants. The Frog Orchid and Moonwort were dealt with in the last Worcestershire Record No. 33 November 2012, as were interesting plants in SP13 above Broadway. There were many other good finds that demand inclusion in this report. With my special interest in dandelions, I must highlight the four new dandelion species (plus one new to vc37). One of these, Taraxacum cherwellense, must compete with the Frog Orchid for plant of the year. This dandelion is a very rare endemic thought to be declining towards extinction. The national dandelion database now has a twelth record, in a new area. Most early records were from VC 23, best known from its type locality in the Oxford Parks where in was first collected in 1928 but was last seen in 1977. Since then there had only been one record, at Blakeney West Gloucestershire, in 1993. In any other year I would enthuse over the two other new natives. dandelions.

I will leave the other records listed below to speak for themselves. As always I am sure other people would have selected a different set of species and I am sorry if I have left out your favorites, but with so many to choose between I had to disappoint many people. In particular I decided to leave out new finds from previously known sites even though these essential for the Maps Scheme and may be rare plants.

In the record details below, “county” refers to the combined area of modern Worcestershire. The symbol * designates first published county records and # first post 1987 hectad records. A + against the species indicates that the taxon is not a native or archeophyte where recorded.

# Anthemis austriaca – Austrian Chamomile +

B4211 Hanley Castle Parish: SO8342: Keith Barnett conf. Bert Reid: About 100, grass or wildflower seeded verge. Second county site.

# Astrantia major – Astrantia +

Broadway disused railway: SP0838: Bert Reid: A small flowering patch in waste area at base by footpath.

Badsey Parish: SP0742: Terry Knight: 1 on NW side of track opposite nursery

* Bergenia x schmidtii – Elephant-ears +

Barnards Green area: SO7945: Keith Barnett: 1 on steep-side ditch bank outside garden, seeming unlikely to have been planted. First county record.

Botrichium lunaria – Moonwort

Lodge Hill Meadow, Wyre Forest: SO7945: John Robinson: one plant – details in Worcestershire Record No. 33.

# Coeloglossum viride – Frog Orchid

Armley Bank, Broadway: SP1136: Roger Maskew: seven plants in limestone grassland at the foot of steep bank, also seen later by Bert Reid. First county record since 1979 – details in Worcestershire Record no. 33.

# Cosmos bipinnatus – Mexican Aster +

Longdon Parish, S of Longdon: SO8435: Keith Barnett: one growing through tarmac pavement near garden, in flower / fruit. 4th county record.

# Cuscuta campestris – Yellow Dodder +

Lambs Farm, Coles Green: SO7651: S. Benjamin det. Tim Rich: On Niger and other plants under bird table in garden. Photographs and voucher in National Museum of Wales. 2nd county record.

Eleogiton fluitans – Floating Club-rush

Hitterhill Copice, Wyre Forest: SO7675: John Bingham: About a dozen small clumps, small pool backwater, about 0.5km SE of previous record near Lodgehill Farm.

* Erigeron annuus – Tall Fleabane +

Wollaston Old Iron Foundry Site: SO8984: Anne Daly: At least seven plants, more than confirmed record in 2011, still not on database. First county record.

* Eryngium planum – Blue Eryngo +

Holloway, Pershore Town: SO9346: Bert Reid: one large plant just coming into flower, growing on verge at base of street light – no sign in nearby gardens. First county record.

# Gladiolus communis ssp. byzantinus – Eastern Gladiolus

Morton Stanley Park: SP0265: Ms. G Thomas det. John Day: two flowering spikes about 50m apart in rough grassland near hedgerow, not seen here previously.

Red House Meadow, Eldersfield: SO7930: Recorders field Meeting (John Day, Bert Reid, Brett Westwood et al): 10 to 20 plants. 3rd and4th county records.

# Guizotia abyssinica – Niger +

Lambs Farm, Coles Green: SO7651: S. Benjamin det. Tim Rich: Under bird table in garden with Cuscuta campestris. 5th county site.

Hieracium sylvularum – Ample-toothed Hawkweed +

The Bank Middle Hill & Armley Bank Wood: SP1134 & SP1136: Bert Reid: Several plants in two new sites.

Hypochaeris glabra – Smooth Cat’s-ear

MOD Oil Pumping Station Titton: SO8269: John Day: Several flowering plants in mown sandy grassland. Threatened plant last seen in this hectad in 1992.

Malcolmia maritime – Virginia Stock +

B4211 Hanley Castle Parish: SO8342: Keith Barnett: Locally frequent, grass or wildflower seeded verge. 5th county record.

# Nonea lutea – Yellow Nonea +

Red House, Eldersfield: SO7930: Recorders field Meeting (John Day, Bert Reid, Brett Westwood , Ms A.Fells): Established as garden weed in several places.

Pershore Town: SO9445: Bert Reid: Several in flower as garden escape on track by house to rear garage.

3rd & 4th county records.

* Oryzopsis miliacea – Smilo-grass +

Priory Park, Great Malvern: SO7745: Keith Barnett det. T.A.Cope: 2, pavement crack, clear escape from garden, in fruit. First county record.

# Phuopsis stylosa – Caucasian Crosswort +

Red House, Eldersfield, grounds & gardens: SO7930: Recorders field Meeting (John Day, Bert Reid, Brett Westwood, Ms A.Fells): Established and showing signs of natural spread, likely from imported stock. 4th county record.

# Phygelius capensis – Cape Figwort +

Wollaston,near VicarageRoad: SO8885: Anne Daly det. Mike Poulton: one plant, under hedge. 2nd county record.

# Polypogon monspeliensis – Annual Beard-grass +

A461 High Street Wollaston: SO8984: Anne Daly: nine plants in pavement by doorsteps and lamp-post. 4th county site,

* Polystichum munitum – Western Sword-fern +

Bewdley, alley between houses: SO7874: Brett Westwood, Field Meeting Wyre Forest Study Group: One plant in shady alley with Male Fern & Harts Tongue Fern. First county record.

Prunella lacinata – Cut-leaved Selfheal +

The Banks Cambridge Farm: SO7836: John Day: On steep south facing slope – 100+ plants occur across the whole bank from SO78243670 to SO78353670 but with the densest concentration in the west. At date of visit only rosettes were found but several were taken and grown on. All produced pure lacinata flowers, no hybrids were found. New county site.

# Rubus odoratus – Purple-flowered Raspberry +

St Wulstans NR, Malvern Wells: SO7841: Keith Barnett: Spreading patch, very possibly relic. 2nd county record.

# Scilla siberica – Siberian Squill +

Great Malvern: SO7846: Keith Barnett: About 30, naturalised in grassy verge, in flower. 5th county record.

# Scrophularia vernalis – Yellow Figwort +

Red House Eldersfield, grounds & gardens: SO7930: Recorders field Meeting (John Day, Bert Reid, Brett Westwood, Ms A.Fells): About 5 plants in shady corner – reported as not intentionally introduced by owner. First recent county record.

# Smyrnium perfoliatum – Perfoliate Alexanders +

Red House, Eldersfield, grounds & gardens: SO7930: Recorders field Meeting (John Day, Bert Reid, Brett Westwood, Ms A.Fells): Established and showing signs of natural spread, likely from imported stock. 2nd county record.

# Taraxacum angulare – Angular-lobed Dandelion +

Appletree Lane, Inkberrow: John Day det. Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Grass verge. 2nd county site for this rare dandelion,.

* Taraxacum cherwellense – Cherwell Dandelion

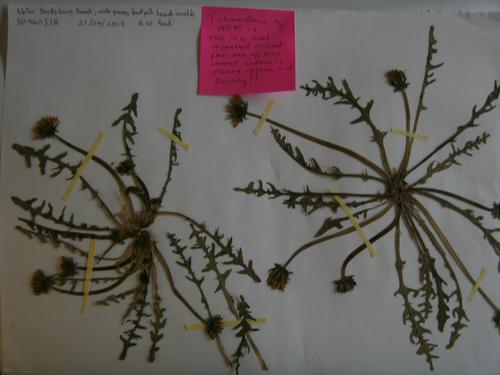

Upton Snodsbury Parish: SO9453: Bert Reid det. John Richards : Wide grass footpath by arable. First county record. AJR states that “This is a most important record for one of our rarest endemics. Please return and survey!!”. See Fig. 1.

# Taraxacum diastematicum – Bulbous-lobed Dandelion +

Lane Shrawley to Hillhampton: SO7765: John Day det. Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Grass verge south side. 3rd county record.

# Taraxacum exsertiforme – Erect-bracted Dandelion +

A4104, SO84, Marsh Common: SO8942: Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Road verge. 3rd county record.

* Taraxacum inopinatum – Unexpected Dandelion

Cambridge Farm, Birts Street, Corner Bank: SO7836: Dry CG3 grassland, steep slope. First county record.

# Taraxacum lunare – Lunar-lobed Dandelion +

Honeybee Public House, Doverdale Lane: SO8566: John Day det. Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Grass verge to car park. 3rd county record.

# Taraxacum melanthoides – Bluish-leaved Dandelion

Heightington Lane: SO7869: John Day det. Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Sandy hedgebank north side – two plants collected. 2nd county record. First record in VC37.

# Taraxacum necessarium – Dark-leaved Dandelion +

Upton Snodsbury Parish: SO9453: Bert Reid conf. John Richards: Wide grass footpath by arable. 2nd county record

# Taraxacum scotiniforme – Deltoid-lobed Dandelion +

Trimpley Lane: SO7980: John Day det. John Richards: Woodbank east side. 2nd county record.

# Taraxacum sublongisqameum – Roadside Dandelion +

A443 Hylton Road by Sabrina Bridge: SO8455: John Day det. John Richards: 3rd county record.

* Taraxacum subnaevosum – Pale-bracted Dandelion

A4189 Henley Road, Oldberrow: SP1265: John Day det. John Richards: 4 plants collected as part of a colony extending over about 100 m of grass road verge, most on south side, less on north. 1st county record for this normally northern species.

* Taraxacum sundbergii – Sundberg’s Dandelion +

Lincomb Lane: SO8269: John Day det. John Richards: Hedgebank east side. First county record for this rare alien.

# Veronica perigrina – American Speedwell +

Stone Cottage Gardens plant nursery: SO8674: Brett Westwood: A few, gravel paths. 2nd county record.

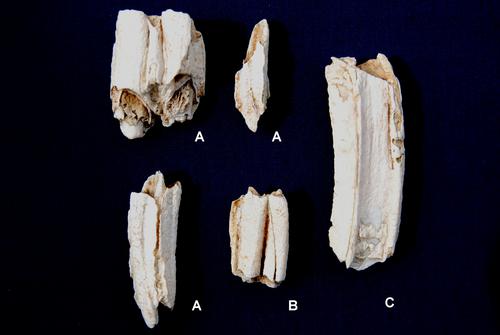

Image

Fig. 1. Taraxacum cherwellense herbarium specimen. Bert Reid

Fig. 1. Taraxacum cherwellense herbarium specimen. Bert Reid

Worcestershire Record | 34 (April 2013) page: 14-15 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Moths in Worcestershire VC37 in 2012

Tony Simpson