Issue 33 November 2012

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 27-29 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Moth Recording in the Teme Valley 2012

Danny Arnold

Teme Valley Wildlife Group

Birchfield is an 18 acre smallholding in the Teme Valley that I am fortunate enough to call home. Not used for making a living, it has become a personal mini wildlife reserve. Almost every night when I’m here throughout the year, I run at least one moth trap in a fixed location, which is supplemented at least once a week by four further traps in four other fixed locations for nine months of the year. So typically having run circa 450 – 500 moth light traps per year for the past five years or so I guess it could quite legitimately be termed, a “constant effort” site, at least for moth data.

And the Teme Valley is proving to be one Worcestershire’s moth ‘hot spots’ owing much to the exceptional quality and diversity of habitat found in the area. Much of the habitat is pristine arising in part from the difficulty of the terrain for farming the land. On the Valley floor and on the Valley sides fields tend to be small and often undulating, a resulting legacy of moraines produced from the receding glaciers of the last ice age. This has tended to restrict arable crops in favour of livestock farming, typically sheep. As such, good hedges are required to contain livestock, which of course, makes for good connectivity corridors for all sorts of wildlife throughout the Valley.

With a good number of springs and water courses coming off the higher ground, dingles have been hewn into the Valley slopes at irregular intervals. These are often deep and relatively inaccessible places resulting in farms fencing off these areas in a bid to keep livestock out. Often left to their own devices, these dingles are relatively unmanaged and somewhat neglected tracts of land that evolve almost ad-hoc, further adding to the biodiversity found in the area. Over the years, they become very important mini ecosystems in their own right, supporting a wide range of often quite specialised flora and fauna.

The ecology of dingles in the area is complex and scantily documented. They are unique in that they cover a full spectrum of changing habitat, turning from dried up gullies in the height of summer to damp, mossy, shaded ravines trickling with spring water, to raging torrents of water during a flash floods, carrying vast quantities of scouring water down into the waiting out-flow into the River Teme below.

It is this tremendous diversity of habitat within the Teme Valley which over the past five years or so has produced almost 800 species of moth, including seven “first records for Worcestershire”. And indeed, every year, sees new species added to the ever increasing area list, that covers the predominantly SO66 Ordnance Survey hectad (10×10 km square)

The latest ‘first record for Worcestershire’ fell to Ken Willetts living on the Highwood at Eastham. Not even having completed his first ever year of moth trapping, his new addiction to the world of moths had him sweep netting his garden flowers for even the smallest quarry. One such specimen caught his attention owing to its striking colouration. Ken forwarded me a photograph of the specimen which I presumed to be a possible new record for Worcestershire 902 Chrysoclista lathamella (Figs. 1& 2). This was later confirmed as such by County Moth recorder Tony Simpson.

Other relative rarities turning up in the Teme Valley this year have been 887 Mompha lacteella, (confirmed by dissection) 463 Ypsolopha vittella and 1272 Pammene aurana all taken by Ken Willetts, confirmed Tony Simpson.

Also 469 Eidophasia messingiella , 891 Mompha sturnipennella (Fig 3), 280 Caloptilia cuculipennella (Fig. 4.) and 515 Coleophora albitarsella have all turned up for the Author, all being confirmed by dissection.

Also of note is the seemingly increasing occurrence of 289 Caloptilia falconipennella (Fig. 5.), unknown in Worcestershire pre 2009, it is now appearing with increased regularity in the moth traps of the Teme Valley. The larva of this species is an Alder feeder, so, with plenty of Alder in the Teme Valley, local habitat profile fits well with this species presence.

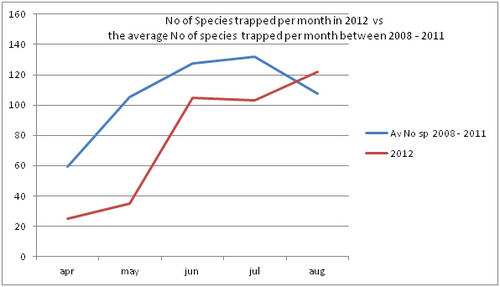

But even with these encouraging signs of hitherto non recorded moth species in the Teme Valley, on the Moth front generally the summer of 2012 has been a poor one for Lepidoptera, reflecting the general status nationally. Moth numbers are down. Species numbers recorded are down. Looking at the data from Birchfield over the summer months from the past five years Graph 1 and 2 (Figs. 6 & 7) clearly outline just how poor a year it has been for moths.

Graph 1 (Fig. 6.) shows the number of spring and summer moth species trapped each month this year (2012), against the average number of moth species trapped over the past four years for the same monthly periods.

This clearly shows a marked decline in the number of species being seen and recorded this year from the Teme Valley. (And if the figures are further drilled down into, but not shown here, it can be seen there is even an apparent general downward trend almost every year over the past five years, indicating this is a continuing trend with 2012 being the worst year in a set of five).

With the exception of a slight recovery in June species numbers recorded would appear to be down around 50% per month, based on monthly average numbers over the previous four years.

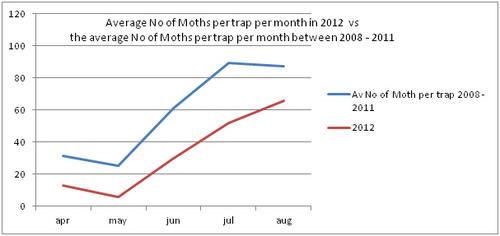

Similar occurrences are also apparent with moth numbers trapped as is seen from Graph 2 (Fig. 7.). There is clearly a significant decline in the volume of moths around as seen from the perspective of the past five years.

Obviously a five year period is only a tiny reflection of a much bigger picture, but underlying trends are at this point undeniable. Lepidoptera populations are in trouble.

The inspiring rewards of the effort of finding new species in the Teme Valley area is contrasted by the downward trend in general species recorded and numbers.

There are no easy answers or quick fixes to the issues. We believe we ‘manage’ our 18 acres with our sights set firmly on wildlife prosperity but even with that focus we appear to be falling short.

Mini studies such as this, with concentrated monitoring and data production from a site such as this, clearly helps to demonstrate trends in the Teme Valley area and may possibly even reflect trends further afield on an even greater scale.

Images

Fig. 1. 902 Chrysoclista lathamella. Ken Willetts

Fig. 1. 902 Chrysoclista lathamella. Ken Willetts

Fig. 2. 902 Chrysoclista lathamella. Ken Willetts

Fig. 2. 902 Chrysoclista lathamella. Ken Willetts

Fig. 3. 891 Mompha sturnipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 3. 891 Mompha sturnipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 4. 280 Caloptilia cuculipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 4. 280 Caloptilia cuculipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 5. 289 Caloptilia falconipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 5. 289 Caloptilia falconipennella. Danny Arnold

Fig. 6. Graph 1 number of moth species per month

Fig. 6. Graph 1 number of moth species per month

Fig. 7. Graph 2 number of moths per month

Fig. 7. Graph 2 number of moths per month

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 55-57 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

An account of one Swift nest in Kidderminster

Mike Averill

This is not an in-depth study, but observations of a Swift nest assisted by the installation of a camera. In 2010 a box designed for Swift use (see Swift Conservation web site for information) was finally occupied after being in situ for about seven years. It was fitted on a building in an area where Swifts are present each year and there are usually two other nests within 100 metres of the house. The box is on the east side of the house with the access hole facing down the road to the south. The box is under the eaves and so is not in direct sunshine. The construction is as per normal recommendations but the entrance was fitted at the end purely because it meant that it would be visible to Swifts flying up the road. In the seven years the box had been up there were only a few occasions when it was inspected by Swifts but no Swifts were seen to enter until 2010. Occupation was first noticed in mid July 2010 and at least one chick was seen to fledge that year with a further egg being found later un-hatched. Swifts are hard to observe at nest sites because the adults do not go in and out very often during the day and so a camera is a must. In 2010 a camera was fitted outside the box trained on the nest entrance and this helped to some extent but it was still impossible to tell what was going on inside. With that in mind, in readiness for the 2011 season an infrared camera was fitted inside the box: the sort commonly used in tit nestboxes. Unfortunately the Swifts did not return to the box in 2011.

Interestingly in 2010 the Swifts actually evicted nesting House Sparrows to use the box and in 2012 Sparrows were once again trying to use the box and so in late April the entrance slot was reduced in size to prevent this. To further encourage the use of the box in 2012, a Swift call recording obtained from Swift Conservation was played during early May. This call consists of the screams of Swifts which already have a nest site and is supposed to stimulate other prospective Swifts to investigate. Whether this worked or not it was with great relief that two Swifts were seen to enter the box on 22nd May 2012 and stay in there all morning. Pairing appeared to take place during that time. Prior to that Swifts had been seen in the area from 31st April 2012.

Table 1 shows the observations during the nesting period which produced one fledged nestling. It was a very prolonged period and something may have happened to interrupt the process as there were signs of some disturbance on the 11th June when nesting material was heaved up, and no birds stayed that night which wass the first time that two Swifts had not roosted in the box since the 22nd May. Unfortunately the box wasn’t observed again until the 20th June but the Swifts had returned and they were occupying the box at night. It was a strange year of course weather wise with prolonged cool wet periods and it is easy to speculate that poor conditions had stalled the nesting process. Whatever went on, the routine overnight occupation of the box by two Swifts was observed uninterrupted from the 20th June to the 28th August. It was difficult to see exactly when the egg was laid as the camera angle was not perfect so it was not until the 1st August that the first glimpse of a chick was made. The following 23 days were spent selfishly by the single chick eagerly greeting the adults who returned with foodballs of flies, making a fuss rather like young mammals do on the return of adults with food. Internal cleanliness was good with the adults taking droppings away and the chick reversing kingfisher style to eject faecal material out of the box hole: another confirmation that the end access hole seems to work well. One interesting fact revealed by the camera was that two Swifts used the box each night. Very often it is assumed that the males do not have much contact with the nest site other than bringing food. Assuming that the two in the box were a pair, both male and female had spells brooding the egg. Pair bonding was reinforced by the one sitting on the nest calling loudly if the other one was out collecting food. As soon as the chick had hatched both adults would go out feeding during the day.

| 22/5/2012 | First attempt to enter nest box today. Many entries and two birds were in the box at dusk. Mating appeared to take place. |

| 23/5/2012 | Both birds out all day returning at 21.08 to stay all night |

| 24/5/2012 | Screaming from box at 10:34. Both Swifts in at 21.09 |

| 25/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 26/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 27/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 21:00 |

| 28/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 08:30 and 22:00 |

| 29/5/2012 | Both birds in and out several times finally entering at 21:15 |

| 30/5/2012 | Two birds in nest box at 21:15 |

| 31/5/2012- 10/6/2012 | Two birds in nest box at night |

| 11/6/2012 | No birds in box overnight |

| 12/6-20/6 | Some sort of disturbance in the box with nesting material being heaved up. Nest was not observed again until 20/6 |

| 20/6/2012 | Two birds screaming from box |

| 21/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 18:11 |

| 22/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 21:25 |

| 23/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night at 21:30 |

| 24/6/2012 -27/6/2012 | Two birds in box for night |

| 5/7/2012 | Two birds in box for night, one stayed all day |

| 14/7/2012-1/8/2012 | At least one bird sitting all day. Couldn’t see it but an egg had been laid |

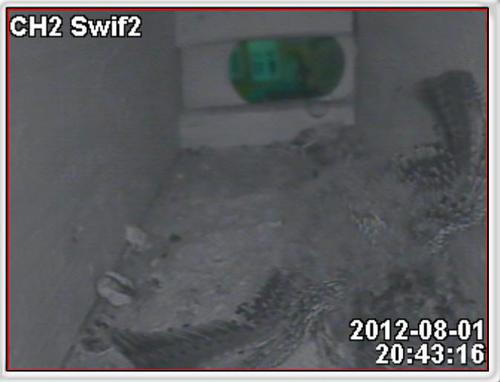

| 1/8/2012 | First glimpse of one chick |

| 6/8/2012-20/8/2012 | Chick becoming more feathered, food balls being brought and adults avidly greeted by chick. Wing stretching and press ups by the chick. |

| 20/8/2012 | Chick fully feathered, adults didn’t come back to box at night. Nestling doing press up exercises regularly. |

| 23/8/2012 | No adults returned since 20/8/2012, juvenile climbed out of the box at 18:15, then climbed back in. Finally bailed out at 21:12 and the louse fly jumped off the chick to stay in the box. |

Table. 1. Record of events in the Swift nestbox in 2012.

The Swift Louse Fly Crataerina pallida was observed during the time that Swifts used the box and seemed to show up quite well when the infrared camera was on. When the adult Swifts were in the box for the night the louse flies were quite active during preening. There appeared to be a definite attempt by the louse fly to sit behind the birds head whilst it dealt with its feathers and would dodge from one side to another of the neck as the bird’s head reached around. What was puzzling was why one bird could not deal with the louse fly on its mate as that appeared to be possible as they sat side by side. It is interesting to speculate that perhaps the Swift does not make too much attempt to remove the fly and research has in fact not as yet found any detrimental effect from having the parasites on them.

Recent studies by Walker & Rotherham (2010) on a complex of Swift roosts in a German bridge have found that the mean parasitic load was between one and seven per nest and that louse fly numbers declined throughout the Swift breeding season. Parasite populations were heavily female biased, except for at the initial and final stages of the nestling period. It is in the interests of the fly not to overburden the Swift but they feed every five days with males taking on average 23 mg and females 38 mg of blood on each occasion (Kemper, 1951); this has been calculated as being the equivalent to 5% of an adult Swifts total blood volume.

An interesting feature of this insect is that it does not lay an egg but broods internally before laying a fully formed larva that immediately starts to pupate. When the pupa hatches into an adult it seeks to associate itself with a bird or seeks a nest of young Swifts. Louse flies are of course vertically transmitted ectoparasites only passing on their young to the same family of Swifts and so the relationship is very close. Observing the Swifts in the nest box it was clear that the louse flies stayed on the adult Swifts as they came and went and there didn’t appear to be more than one per adult. It was difficult to be sure of that though as they completely disappeared under feathers but what can be said is that no more than one was ever visible on the adults at any one time.

The literature implies that the pupated louse flies associate themselves with the young chicks as soon as they hatch but some must take up residence on the adults. Doing this they will spend many hours hurtling at up to 70 m.p.h. as the adults search for food and their flat bodies seem well adapted for this. What was most interesting was that the final minutes before the juvenile Swift left the box were observed and when the Swift bailed out for its maiden flight the louse fly was seen to jump off. How that louse fly knew it was time to do that is amazing. After the fledgling had left, the louse fly was clearly visible on the inside wall of the box. The flies would of course not want to go anywhere but would need to deposit the larva to pupate and wait until the following spring when the Swifts return. The other interesting question is how the louse flies that are on the adults know when those adults are not going to return to the box because it is a fact that the adults do desert the young who have to make the long trip to Africa on their own. In my box the juvenile Swift was left for four days on its own before it decided it was time to go.

Swifts now rely heavily on buildings for nest sites in the UK and they are under pressure from home owners as repairs are made to house roofs. Ideally Swifts should be given the same sort of protection that is afforded to bat roosts but it is encouraging that they will use artificial boxes and the hope is that more will be installed by householders in the future. Who would want a world without the scream of Swifts in the summer!

References

Walker, M.D. & Rotherham, I.D. 2010. Characteristics of Crataerina pallida(Diptera: Hippoboscidae) populations; a nest ectoparasite of the common Swift, Apus apus (Aves: Apodidae). Experimental Parasitology,126(4): 451-455.

Kemper, H., 1951. Beobachtungen an Crataerina pallida Latr Und Melophagus ovinus L. (Diptera, Pupipara). Zeitschrift fiir Hygiene (Zoologie)39:225–259.

Swift Conservation web site www.swift-conservation .org

Images

1 -Two Swifts in the box on the first day

1 -Two Swifts in the box on the first day

2 – The Louse Fly on an adult

2 – The Louse Fly on an adult

3 – First Sighting of the Chick

3 – First Sighting of the Chick

4 – The chick reversing up to the entrance to defecate

4 – The chick reversing up to the entrance to defecate

5 – A Louse Fly on the chick

5 – A Louse Fly on the chick

6 – The young chick probably three weeks old

6 – The young chick probably three weeks old

7 – The first attempt to leave the box failed

7 – The first attempt to leave the box failed

8 – Crataerina pallida from wikipedia

8 – Crataerina pallida from wikipedia

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 26-27 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Dragonflies in Worcestershire 2012

Mike Averill

What a year of weather extremes; from drought in March to floods in July. The summer (Apr-Sep) was very wet with over 150% of annual average rainfall compared to 58% for the same period in 2011. Consequently it was a case of picking the days very carefully for insect watching. The only consolation would be that aquatic insects would not need to search far for wetland habitat.

After a very warm dry start in March when early flowering plants did well for pollination, a wet and cool April brought frosts and this delayed much insect activity. The Common Clubtail Gomphus vulgatissimus didn’t emerge until late May, as much as 14 days later than in 2011 but it wasn’t a bad year for them and they all emerged in a very short two week period making up for lost time.

It has been mentioned in previous years that the Beautiful Demoiselle Calopteryx virgo has been doing well and this was the case again with the species showing in as many numbers and locations as the more commonly encountered Banded Demoiselle Calopteryx splendens. Twenty years ago a walk up the river Teme would reveal few Beautiful demoiselles other than in the minor tributaries but this year they were to be seen alongside the Banded Demoiselle in most places. The species is also being reported from smaller rivers east of the Severn as well.

All dragonflies and all the damselflies except for the demoiselles have a true colour cell in the wing (pterostigma). Of the demoiselles only the females have the equivalent to a pterostigma in that it is a coloured area of cells near the front edge of the wing (Fig. 1.) as opposed to the enlarged single cell as seen in all other dragonflies. Sometimes this is missing even in the females and is rarely recorded but a Banded Demoiselle without one was seen in Kidderminster in late May this year (Fig. 2.).

Immigration of dragonflies from the continent occurred as usual in to southern England but only the Red-veined Darters Sympetrum fonscolombiireached Worcs this time with a few being seen at Grimley Gravel Pits, Pirton Pool, and a few at Kemerton gravel pits.

The Scarce Chaser Libellula fulva continues to expand its range with records occurring at Pendock, Churchill, Hurcott and most surprisingly at Hillditch Pool. All those sites are pools and so are not really the classic river habitat that it is normally associated with this species. Of those sites Hillditch is perhaps the most surprising as there was quite a lot of breeding activity and this site, although small, could be mistaken for a river as for about a hundred metres it does look like a very slow flowing medium sized river. Like most dragonflies the males of the Scarce Chasers are the most noticeable as they adopt display territories but females were seen as well with up to 12 individuals pairing up. Next season will be anticipated with interest to see if the population increases at this site.

The Small Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma viridulum appeared to be making a relentless push westwards after initially appearing in Essex in 1999, but there seems to be some evidence that it is slowing its progress. It first appeared in Worcestershire in 2006 and has centred its activity at Croome Park. Last year the numbers were in the hundreds possibly thousands but this year they were down to a few hundred. That may be weather related and it could be due to less algal growth, one of its preferred plants, which being more likely to develop in hot weather, is also weather related. The damselfly prefers water milfoil and hornwort but is quite happy on blanket weed. Attempting to estimate damselfly numbers is rather subjective but having the started transect counts at Croome this year has helped make comparisons.

There is not much colour variation in mature dragonflies in the UK but it can be seen in the Aeshnid species, specifically the Southern Hawker Aeshna cyanea. Both the males and females can be seen with all the abdominal colour spots showing as light blue rather than green and the thoracic shoulder stripes appear yellow rather than green (Figs. 3 &4.) It is not mentioned in most identification books and the cause is not fully understood but is thought to be either related to temperature, to stages of development or is a colour form.

Colours will generally go lighter with heat, the point being to enable incoming radiation to be reflected back out. The reverse is the case in cooler weather and may be why the Highland Darter Sympetrum nigrescensis darker being located in Scotland where radiation will be less. This theory is not favoured by observers in Scandinavia where they argue that it should, in that case, be much more commonly seen in the cooler climates.

With ageing, colours normally change in the days immediately after emergence as the individual matures. In the later stages of adult life, individuals will also develop a darker colour and some very old adults like females of the Common Darter Sympetrum striolatum will start to take on the hues of the males.

Many of the examples cited as having blue colouration appear to have recently emerged and it could be that they are just a transitional phase before adopting the normal colours. Again if this is the cause it is strange it isn’t seen more often in a well observed group like dragonflies.

Some damselflies like the Ischnurids, show colour variation in females, the Blue-tailed Damselfly Ischnura elegans has various colour forms and this is called polychromatism (only the females show this) whereas polymorphism is where the males and females show colour differences between each other. Polychromatism isn’t usually encountered in the larger UK dragonflies and so blue forms in the Aeshnids is unusual. We have had a handful of these sightings in Worcestershire all in the Southern Hawker. Both males and females can show the effect. In order to test the temperature and ageing theory a live specimen was collected this summer near Pershore where there were two females hawking a hedgerow. It was fed on mosquitoes in a summer house for four days until it unfortunately broke its neck trying to get out, but in all the time it was there, the colour didn’t change at all (photos). This was despite the temperature ranging from 9 to 27°C. Perhaps this individual can reveal something from its DNA.

The damp cool summer continued in to September and so the flying season was all but over by mid September with just the hardy Common Darters, Migrant and Southern Hawkers Aeshna mixta and Aeshna cyanea making the odd appearance on warmer days.

2012 was a bit disappointing for the last year of recording for the National Atlas, nevertheless the survey time is complete and the full details will appear in the next issue of the Worcestershire Record.

Images

Fig. 1. Banded Demoiselle (f) with pterostigma. Mike Averill

Fig. 2. Banded Demoiselle (f) without pterostigma. Mike Averill

Fig. 3. Southern Hawker (f) blue form. Mike Averill

Fig. 4. Southern hawker (f) blue form side view.Mike Averill

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 9-11 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Invertebrate Records from a Worcestershire Garden 2012

Denise Bingham

This year it seemed that our garden in Kidderminster was a good place to be as several unusual and rare species turned up. Guess it goes to show that keen observation of a small area can provide some good finds! Thanks to John Bingham who did some of the identification of my various finds.

Andrena nigrospina, (Thompson, 1872). Hymenoptera: Andrenidae . RDB1(Red Data Book).

This RDB1 solitary bee is well known to local naturalists at its Blackstone Nature Reserve site near to the heathlands of Devil’s Spittleful. (Trevis 2009). A large black bee was seen in the garden on 20 July feeding on Rosa mundi. It was caught and very surprisingly we identified it as Andrena nigrospina. Having made some effort to see this bee at Blackstone over the last few years we could hardly believe it had appeared in the garden. A photograph was sent to Geoff Trevis who confirmed our identification. Our garden is within 0.5km of acidic semi-improved sandy grassland at Hurcott so we can only assume the bee had flown somewhere from there where it may nest to find nectar on our garden plants. This links in with Brett Westwood’s sightings of the bee at Ismere about 2km to the north.

Tiphia femorata, (Fabricus,1775). Hymenoptera:Tiphiidae.

This rather odd-looking wasp which looks more like a rove beetle than a wasp was found on garden flowers on 25 August. The wasp is a parasitoid on scarabaeid beetle larvae (recorded hosts include Aphodius, Rhizotrogusand Anisoplia). The female burrows into the soil to find a larval host in its cell, stings the larva and kneads it with her mandibles. An egg is laid on the larva which hatches to produce a larva which takes about three weeks to consume its host. (BWARS web site). Thanks to Geoff Trevis who confirmed our identification and reported that Andy Jukes has recorded it at Blackstone and Burlish Top.

Sehirus luctuosus , (Mulsant & Rey,1866). Hemiptera: Cydnidae.

After Jane Scott’s report in Worcestershire Record (No32 April 2012, p.27) the hunt was on to find this shieldbug as Forget-me-not was common in our garden. On a sunny day on 8 May I found one on the garden path, thereafter many were seen over the following weeks near Forget-me-not plants. We were spotting them running around on bare soil next to Forget-me-not flowers. Difficult to estimate numbers but certainly dozens must have been present in several areas of the garden. Not to be out done John Bingham searched Forget-me-not plants on the Devil’s Spittleful NR and managed to locate two bugs on 23 May. They do hide under the leaves but in warm weather are quite active and can be seen running over bare ground or on pathways near the host plant.

Volucella inanis, (Linnaeus, 1758). Diptera: Syrphidae

This hoverfly is now well established in the county but still rather scarce in north Worcestershire. It did finally turn up in our garden on 16 August. In the following week several more were seen, both male and female.

Chrysotoxum verralli, (Collin, 1940). Diptera: Syrphidae

I saw several of these attractive hoverflies on 8 July seen taking nectar from various flowers.

Stratiomys potamida, Meigen, (1822). Diptera:Stratiomyidae, Solider-fly.

This attractive solider-fly, the Banded General, is a local species associated with wet places such as pools or carr woodland, occasionally recorded around the county (Stubbs and Drake 2001). So it was not expected to appear in our garden feeding Leucatheum spp. flowers. I recorded it on 19 August and saw another one a few days later. The nearest wet site is Podmore Pool with its carr woodland backwater some 0.5 km distant.

Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii , (Brandt, 1833). Arthopoda: Isopoda

I found a colony of a small white woodlouse on the edge of the garden lawn on 23 June that was identified as Playtharthrus hoffmansegii. The distinctive blind woodlouse is apparently common in Worcestershire but Kidderminster is near the northern limit of this species. A number of Lasius niger ants were nearby and appeared to be associated with the woodlice. The Woodlouse Atlas (Gregory 2009) says it tends towards calcareous soils, perhaps because they warm up quickly.

References / Information

Bantock & Botting, British Bugs; www.britishbugs.org.uk

Gregory, S. 2009. Woodlice and waterlice (Isopoda:Oniscidae & Asellota) in Britain and Ireland. FSC Publications. Preston Montford.

Scott, J. 2012. Interesting bugs at Woodbank, Astley Burf, 2011 Worcestershire Record. 32:27.

Southwood, T. & Leston, D. 1959 Land and Water Bugs of the British Isles. Warne.

Stubbs, A & Drake, M. 2001. British Soliderflies and their Allies. British Entomological and Natural History Society.

The UK Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society (BWARS). www.bwars.com

Trevis, G. (2009) Andrena nigrospina. Worcestershire Record. 27:23.

Images

Fig. 1. Andrena nigrospina

Fig. 2. Tiphia femorata

Fig. 3. Sehirus luctuosus

Fig. 4. Volucella inanis

Fig. 5. Chrysotoxum verralli

Fig. 6. Stratiomys potamida

Fig. 7. Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 7-9 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Invertebrate Records from Worcestershire

John Bingham

[Correction: original reference to Trox scaber, (Linnaeus, 1767). Coleoptera: Trogidae (Fig. 01. deleted) was in error.]Trachys minutus, (Linnaeus, 1758). Coleoptera: Buprestidae RDB2 and LBAP

This small beetle (3-4mm) was found on 26 August on a small-leaved lime leaf at Shrawley Wood. The tree was next to an open glade area and was in full afternoon sunlight. The female beetle lays eggs on the leaves of deciduous trees, normally sallow, hazel or elm. The larvae eat the green tissue between the upper and lower layer of the leaves, making blotch mines on the edge of the leaf. It may use lime tree leaves at Shrawley, as this is also quoted as a food plant for the larvae. See Web pages: ‘the leaf and stem mines of British flies and other insects’ for image of the leaf mine. Alexander (2003) gives it as an elusive species with leaf mines on willow in ancient semi-natural woodlands. He states that the majority of the records are old and the species has decreased parallel with the decline in active coppice management, woods being too dark and shady for the southern warmth-loving species. The beetle was recorded by Ross Piper on 15/05/2002 also from Shrawley Wood, apparently this is the only site in Worcestershire for this beetle. WBRC (Worcestershire Biological Records Centre). Thanks to Harry Green and John Meiklejohn for supplying information on the records.

Pyrrhidium sanguineum, ( Linnaeus, 1758), Coleoptera: Cerambycidae

Several records of the this longhorn beetle have been found in Wyre Forest but this time a small colony of several dozen was found by Denise Bingham under the bark of a standing dead oak tree. The site was near the Dowles Brook on the Worcestershire side on a tree deliberately ring-barked for deadwood habitat. Good to know these trees do attract rare deadwood species! (no picture).

Platycis minutus, (Fabricius, 1787). Coleoptera: Lycidae, Nationally Scarce B

Discovered on the ‘great bog’ in Wyre Forest by Denise on a rotten wet log on 28 August. Four species of Lycidae (net-winged beetles) occur in Britain. The common name ‘net-winged’ refers to the pattern of raised ridges on the elytra. The larvae develop in large relatively soft moist decaying heartwood, especially beech Fagus and probably ash Fraxinus; mostly in closed-canopy areas of ancient woodland; southern and eastern England. (Alexander 2003).

Interestingly more records came to light for 2012. We recorded another beetle this time on the Cotswolds near Rodborough; Dave Scott found one at Astley and Rosemary Winnall found one at Bliss Gate. Perhaps a good year for this species?

Clytra quadripunctata, (Linnaeus, 1758). Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae

This large beetle is associated with wood ant nests Formica rufa. It appears to be quite common and widespread in the Wyre Forest area but not often seen. Over a dozen records are on WBRC database and all are from the Wyre Forest possibly the only location for this species in Worcestershire. This year I found the beetle at Ribbesford Woods on bracken near to wood ants. In the same area several Scarce 7-spot ladybirds Coccinella magnificawere also noted.

Andrena apicata, (Smith, 1847). Hymenoptera:Andrenidae, Nationally Notable B.

Good numbers of this early flying solitary bee were seen on 22 March along a sandy track on the Devil’s Spittleful/Rifle Range. Both male and females were noted in good numbers and many were resting on gorse stems or tree trunks. It appears to be rare in Worcestershire with only one other record at Bliss Gate, Wyre Forest. Geoff Trevis kindly identified the bee.

Lasiopogon cinctus, (Fabricius, 1781). Diptera:Asilidae, Nationally Scarce.

Several of these flighty robber-flies were seen at Hartlebury Common on 24 April. They were hunting for various small flies over the open heathland. Luckily when a prey item was caught the fly settled on the ground allowing observation and photography. The only previous records were made by Andy Jukes at Devil’s Spittleful and Hartlebury Common, both in 2010. (WBRC records).

Chrysotoxum arcuatum (Linnaeus, 1758). Diptera: Syrphidae

This is smaller than the other similar looking Chrysotoxum species and more common in upland areas, so it is uncommon in Worcestershire. Several were noted just over the county boundary at Longdon Wood, Wyre Forest on 28 August. More than likely it can be found on the Worcestershire side as well.

Grapholita internana, (Guenée, 1845). Lepidoptera:Tortricidae

This small moth was seen in good numbers flying around gorse bushes at Hartlebury Common on 24 April. Apparently, despite suitable habitat, it is quite uncommon in Worcestershire with previous records from the Malverns, Old Hills, Hartlebury Common, and the Worcestershire part of Kinver Edge. (Tony Simpson per. comm.)

Neottiglossa pusilla, (Gmelin, 1789). Hemiptera:Pentatomidae, National Local.

This small brown shieldbug 4-5mm long appears to be near the edge of its range being more common further east in Britain. On 5 June I found two at Shrawley Wood resting on a grass stem along a sunny ride. Later on 28 June just over the county boundary in Shropshire Denise found another specimen on a grassy ride at Malpass Wood, Wyre Forest. Probably an overlooked species, the larvae are said to feed on Poa grass species. (Evans and Edmondson 2005). There are only a few records from Worcestershire, one in 2006 by John Partridge at Hawkbatch, Wyre Forest. It may prefer more acidic grasslands and possibly sandy soils limiting its distribution in the county perhaps? Sweeping taller grasses with a net might find it. Rosemary Winnall also reported a discovery on 23 June 2012 from the Shropshire side of the Dowles Brook.

Corizus hyoscyami, (Linnaeus, 1758). Hemiptera: Rhopalidae.

Now becoming quite widespread with records by Denise from Wyre Forest at Longdon Wood, Shropshire, on 28 August. I found it at Blackstone Nature Reserve near Bewdley on arable fields on 31 August. (No picture).

Pholidoptera griseoaptera, (De Geer, 1773). Orthoptera: Dark Bush Crickets.

The abundance of this species at Shrawley Wood was quite notable in August and September in 2012. Nearly every sunny patch was crawling with dozens of crickets many of which looked larger than normal. Yet a few miles to the north in Wyre Forest they remain an uncommon insect more restricted to the River Severn area and a few locations around the forest. I have seen the occasional insect along the Dowles Brook valley but as yet they do not appear to be along other forest rides. Perhaps just a matter of time?

References / Information

The leaf and stem mines of British flies and other insects. http://www.ukflymines.co.uk/Beetles/Trachys_minutus.php

Southwood, T & Leston, D. 1959. Land and Water Bugs of the British Isles. Warne.

Bantock & Botting, British Bugs; www.britishbugs.org.uk

Hawkins, R. 2003. Shieldbugs of Surrey. Surrey Wildlife Trust

Alexander, K.N. A. 2003. Provisional Atlas of the Cantharoidea and Buprestoidae (Coleoptera) of Britain and Ireland. Biological Records Center

The UK Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society (BWARS) www.bwars.com

Evans, M. & Edmondson, R. 2005. A photographic guide to the Shieldbugs and Squashbugs of the British Isles. WGUK in association with WildGuideUK

Images

Fig. 01. Deleted (was an error)

Fig. 02. Trachys minutus. John Bingham

Fig. 03. Platycis minutus. John Bingham

Fig. 04. Clytra quadripunctata. John Bingham

Fig. 05. Andrena apicata Female. John Bingham

Fig. 06. Andrena apicata Male. John Bingham

Fig. 07. Lasiopogon cinctus. John Bingham

Fig. 08. Chrysotoxum arcuatum. John Bingham

Fig. 09. Grapholita internana. John Bingham

Fig. 10. Neottiglossa pusilla. John Bingham

Fig. 11. Pholidoptera griseoaptera Dark Bush Cricket. John Bingham

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 50-53 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Waxcap and other fungi near Stourbridge – an Update

John Bingham

In April 2011 Rosemary Winnall reported in Worcestershire Record (Winnall 2011) the discovery in 2009 of a waxcap grassland, or rather a series of waxcap garden lawns at Broome near Hagley, Worcestershire. The owner David Taft was very obliging and allowed further access in the autumn of 2011 when Rosemary asked several mycologists to help with the survey of the fungal mycota of David’s lawns. Little did we know what would develop from this waxcap survey. Rosemary has asked me to report the findings.

The four lawns date from about the time the house was built around 1906 and appear to have been landscaped as they are flat but on slightly different levels. The largest is about 0.1ha in area. The soil is derived from the sandstone typical of the Kidderminster area and would naturally support acid grassland or heath. The lawns are dominated by mosses with some lichen patches suggesting semi-improved grassland such as NVC U1 (Festuca ovina-Agrostis capillaris-Rumex acetosella grassland), but generally more characteristic of MG6 (Lolium perenne – Cynosurus cristatusgrassland), albeit with a very moss dominated sward. Botanically the lawns were not particularly rich supporting mainly rosette forming species such as Cat’s-ear Hypochaeris radicata. No fertilisers or chemicals had been used for many years, if ever?

I made my first visit on the 15th November 2011 together with Rosemary and Denise Bingham. Rosemary had already recorded good numbers of Hygrocybe calyptriformis (Pink Waxcap) the previous week. Waxcaps were present in good numbers, and recording was carried out. After searching the first lawn I moved to the second larger lawn and after about 10 minutes I spotted a small fungus I was familiar with: Squamanita paradoxa(Powdercap Strangler). I could hardly believe it. At first three were found then after some excitement by all concerned Rosemary found some more specimens making at total of nine fruiting bodies. We believe this is the first county record for the species.

Squamanita pardoxa is listed as Vulnerable in Red Data (RDB) List edition 1 and Near Threatened in RDB List edition 2. It appears to occur at 15 sites in the UK and I personally have been responsible for finding two sites back in 2005 (Bingham & Bingham 2005). Denise and I had added another two sites from Shropshire in 2011 (Titterstone and Brown Clee Hills), that is excluding the site at Broome. Globally the fungus is rare with most records coming from Norway and Sweden. What makes S. paradoxa particularly interesting is the fact it is a parasite on other fungi, within the Cystodermagenus and in particular C. amianthinun (Earthy Powdercap) that appears to be the host for all UK specimens. It takes over its host and is a gall or ‘cecidiocarp’ first described in 1948 but not fully understood until 1965 (Redhead et al.1984) when it was described further. S. paradoxa is a member of the Tricholomataceae family with 10 species in total world-wide.

It grows with the stem of the Cystoderma and replaces the upper stem and cap of the orange coloured Cystoderma with its own greyish cap. Exactly how is still not understood but Gareth Griffith is undertaking research at Aberystwyth University (Matheny & Griffith 2010). I forwarded a photo of the Broome find to Gareth and immediately came a request for a specimen for his DNA research at Aberystwyth. Several specimens were sent and are now in culture with Cystoderma to see how the ceidicarp develops with the Cystoderma host.

A return visit was made to Broome on the 17 September with David Antrobus who was identifying Entoloma fungi, Mark Lawley to look at bryophytes and Brett Westwood who had an idea for a BBC Radio 4 item on grassland fungi. All this was much to the surprise and interest of David Taft and his gardener David Elder, who were both very helpful and welcoming to our strange antics. In due course Brett recorded a feature with Rosemary and me on grassland fungi, duly broadcast on the TheLiving Worldprogramme (http://www.bbc.co.uk/search/?q=Powdercap strangler or http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/16029977) with my photograph of S.paradoxa on the BBC Nature webpage.

In Fig. 1. note the orange colour of the lower stipe which is the Earthy Powdercap Cystoderma amianthinun forming a stocking-like ring above which is the grey Powdercap Strangler Squamanita paradoxa stipe and cap.

Of course we did record the waxcaps with (total for all years) 14 Hygrocybespecies, nine Clavariod, one Geoglossaceae and three Entolomas. (See Table 1).

This is a very respectable list given that a score of 10-11 Hygrocybespecies, 5-6 Clavariod, 4 or more Geoglossium and 8-9 Entolomas are considered to make a site of national importance. (Nitare 1988). David Boertmann in his book on Hygrocybe has a table showing a score of between 11-15 Hygrocybe as being of regional importance and with 16-20 species being of national importance. (Boertmann 1996).

Of course there will be more to discover, certainly Entolomas were under recorded due to the dry weather and a late flush in 2011. More recording would certainly be of interest at such a rich site.

| Name of fungus | Associated Organism | Medium | Ecosystem | Frequency | Date |

| AGARICALES | |||||

| Agaricus augustus | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Arrhenia retiruga | Moss | soil moss | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Auriscalpium vulgare | Pinus | cone | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Calocybe carnea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Clitocybe fragrans | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Clitocybe rivulosa | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Conocybe apala | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Cystoderma amianthinum | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Dermoloma cuneifolium | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Entoloma infula | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Entoloma jubatum | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Galerina clavata | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Galerina vittiformis | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Galerna pumila | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe calyptriformis | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe ceracea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe chlorophana | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe coccinea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe flavipes | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe irrigata (uguinosus) | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe laeta var. laeta | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe miniata (strangula) | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe pratensis | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe psittacina | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe punicea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe reidii | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe russocoriacea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrocybe virginea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Hygrophoropsis aurantiacum | Pinus | soil grass | Garden | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Inocybe pusio | Pinus | soil bare | Garden | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Inocybe sindonia | Pinus | bare soil | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Laccaria laccata | Pinus | soil grass | Garden | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Lactarius deliciosus | Pinus | soil needle | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Lactarius glyciosmus | Pinus | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Mycena aetites | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Mycena avenacea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Mycena clavularis | Gramineae | cone | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Mycena flavoalba | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Mycena pura | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Panaeolina foenisecii | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Panaeolus olivaceus | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Paxillus involutus | Angiosperm | soil | Garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Rickenella fibula | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Rickenella swartzii | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Russula gracillima | Betula | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Russula nigricans | Betula | soil grass | Garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Squamanita paradoxa | Gramineae | soil moss | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Stropharia caerulea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 17/11/2011 |

| Stropharia pseudocyanea | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Suillus luteus | Pinus | soil needle | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| APHYLLOPHORALES | |||||

| Bjerkandera adusta | Angiosperm | stump | Garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Clarvaria acuta | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Clarvaria fragilis | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavaria argillacea | Gramineae | soil moss | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavulinopsis corniculata | Gramineae | soil moss | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavulinopsis fusiformis | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavulinopsis helvola | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Frequent | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavulinopsis laeticolor | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Clavulinopsis luteoalba | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Occasional | 15/11/2011 |

| Geoglossum fallax | Gramineae | soil moss | Grassland lawn | Rare | 08/11/2010 |

| Hypomyces aurantius | Polypore | fruit body | Grassland lawn | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Phellinus pomaceus | Prunus | branch | Garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Polyporus durus | Angiosperm | stump | Garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| Ramariopsis kunzei | Gramineae | soil grass | Grassland lawn | Rare | 30/11/2009 |

| HETEROBASIDOMYCETES | |||||

| Auricularia auricula-judae | Sambucus | stem | garden | Rare | 17/11/2011 |

| ASCOMYCETES | |||||

| Peziza badia | Angiosperm | soil bare | garden | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

| Rhyisma acerinum | Acer | leaf | garden | Frequent | 17/11/2011 |

| Trochila ilicina | Ilex | leaf | garden | Frequent | 17/11/2011 |

| MYXOMYCETES | |||||

| Sebacina incrustans | Gramineae | soil grass | Garden | Rare | 15/11/2011 |

Table 1 Fungi recorded at The Croft, Broome, Worcestershire, November 2011 by John Bingham, Denise Bingham, Rosemary Winnall, David Antrobus. Site SO897790, garden lawn, mossy, unfertilized for 50 years.

In addition to the fungi we have Mark Lawley’s list of associated bryophytes.

The lawns consisted mainly of moss but with no notable species. Mark recorded the following 39 bryophytes from the garden. Nearly all the moss in the lawns is Rhytididadelphus squarrosus, with much less Atrichum undulatum, Brachythecium albicans, B. rutabulum, Hypnum cupressiforme, H. jutlandicum, Plagiomnium rostratum, P. undulatum, Polytrichum juniperinum, P. piliferum, and Lophocolea bidentata. Hypnum jutlandicumand the two Polytrichum species were growing only in sandy (or sandier) soil in the lawn beside the drive. There was also a noticeable amount of Cladonia lichen there too.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to David Taft for his kindness and access permission.

References

Bingham, J. & Bingham, D. 2005. Squamanita paradoxa in Shropshire. Field Mycology 6(1):11–12

Boertmann, D. 1996. The Genus Hygrocybe. Fungi of Northern Europe. Danish Mycological Society.

Mathey, P M. & Griffith, G. W. 2010. Mycoparasitism between Squamanita paradoxa and Cystoderma amianthinum (Cystodermateae, Agaricales). Published online.

Nitare, J. 1988. Jordtunger, en svampgrupp pa tillbakagang I naturliga fodermarker. Svensk. Bot. Tidskr. 82:341-368.

Redhead, S.A., Ammirati, J.F., Walker, G.R., Norvell, L.L. & Puccio, M.B. 1994. Squamanita contortipes, the Rosetta Stone of a mycoparasitic agaric genus. Can. J. Bot. 72:1812–1824.

Winnall, R. 2011. Waxcap Fungi Near Stourbridge. Worcestershire Record30:35-36.

Image

Fig. 1. Squamanita paradoxa. John Bingham

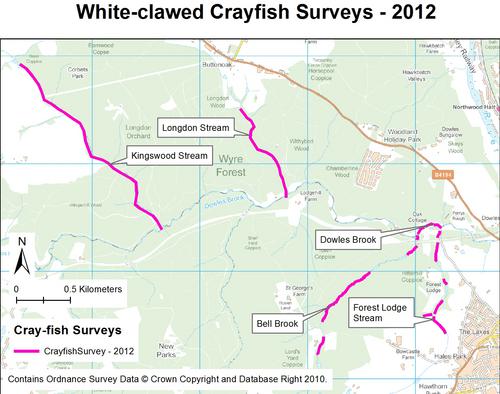

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 42-43 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Bechstein’s Bat – a study on the population size, foraging range and roosting ecology at Grafton Wood, Worcestershire, 2012. A preliminary summary of findings

Johnny Birks, Eric Palmer and James Hitchcock

This article follows on from The National Bechstein’s Survey and Beyond in Worcestershire Record (Sedgeley et al 2012), which outlined the efforts to identify the presence of Bechstein’s bat in Worcestershire, and the subsequent successful bid for funding from the Peoples’ Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) for further studies. The funding enabled us to carry out a radio tracking project aimed at increasing our knowledge of the roosting and foraging habitats of Bechstein’s Bat in a managed woodland. Worcestershire Wildlife Trust initiated the work, in partnership with Johnny Birks and Eric Palmer, following the record of a lactating female Bechstein’s Bat at Grafton Wood which indicated there was probably a colony of the bats living in, or around, the wood. Since Grafton Wood became a nature reserve in 1997, its management has been driven mainly with invertebrates in mind and their need for open space and high light levels. This management has been very successful in encouraging diversity and increasing butterfly numbers and breeding birds. However, past studies have shown (Schofield & Morris, 2000) that Bechstein’s bats favour foraging under closed canopy woodland with a strong understorey (Harris & Yalden 2008) which is well represented in Grafton Wood (Fig. 1.), alongside the actively managed rides and coppice plots. So, it was felt a detailed study to aid understanding of how the bats use the wood was much needed and would provide information for the management plan and ensure that bats were considered alongside other species in the future.

The project depended largely upon a very successful collaboration with the Worcestershire Bat Group whose members committed a huge amount of time and energy helping with catching (using harp traps and mist nets) and radio-tracking Bechstein’s bats at Grafton Wood through the rain-soaked summer ot 2012. We are indebted to them for their massive contribution and their remarkable ability to stay cheerful through the wettest and muddiest summer in 100 years.

Well, what did the project find out? At the time of writing the detailed analysis of data is still taking place, but, we can share some preliminary findings.

Despite the best disruptive attempts of the awful weather, tagging and radio-tracking was carried out, as planned, across three main survey periods: May, June and end August/beginning of September – chosen to avoid catching bats when they would be heavily pregnant or feeding young.

Our early season catch was almost entirely of underweight bats of all species, with additional problems due to a higher than average tag failure rate and of course the weather. Despite this we were able to fit one tag in May and start the process of chasing bats around in the dark. By the end of the season we had fitted a total of eight tags, four less than was hoped and had identified eleven day-roost trees – five in Grafton Wood and six outside. Tree species used were Willow(3), Oak(4), Ash(3) and Silver Birch(1). None of the roosts were in old woodpecker holes, one in a natural rot hole and the other (a lone male bat) in a crack. Through the identification of roosts we were able to carry out timed roost emergence counts which gave us a maximum count of 50 bats which emerged from a woodpecker hole in a Crack Willow pollard.

Of the roosts outside the wood the furthest away was just over 1.5km south. This kind of distance has been recorded in other studies, but was still something of a surprise to us, especially given that the area to the south of the wood happens to be the least wooded area around Grafton Wood.

Overall, we found a bias in bat activity towards the south of the wood, both in terms of roosting and foraging within the wood and the roosts outside of it. Roosts were often near water – the Piddle Brook or a farm pond – which could be a coincidence or it could highlight a need for flight corridors.

Tracking foraging bats revealed that they favour discrete areas of closed-canopy woodland with a strong understorey, which confirmed much of what we had read about the bats in previous studies. However, our late-season animals also foraged around field edges, plantation woodland and along watercourses.

The radio-tags allowed us to confirm that the colony frequently switched roosts, often en masse, which may have been a result of the inclement weather, but may highlight other needs: the bats may move regularly to prevent the build up of waste and parasites, which may increase the risk of disease. Frequent roost switching does bring home the importance of the availability of a wide variety of potential roost trees, in a variety of settings, with woodpecker holes (and other cavities) in them.

The final report will aim to characterise the roost trees, define and characterise foraging areas and perhaps shed some light on what features of the landscape around the Wood really are the most important habitat for commuting and foraging Bechstein’s Bats.

One thing that we can say at this stage is that despite the challenges presented by the weather and the demands of night-time radio-tracking faced so bravely by our band of volunteers, we have hugely increased our knowledge and understanding of Bechstein’s Bat in Grafton Wood and its environs. And it appears that we have a healthy sized breeding colony. As with all scientific field studies we have only just begun to scratch the surface and there is still much more to learn and more work to be done. We hope to follow up this study with the introduction of 100 roosting boxes – woodcrete Schwegler 2FNs – into Grafton Wood which, if used, will allow us to monitor the colony size and, if we can organise ringing the bats, we will hopefully be able to gather data on other important population parameters.

These are exciting times! A full update will follow after the report is published

Notes

Grafton Wood Nature Reserve is jointly owned and managed by Worcestershire Wildlife Trust and Butterfly Conservation.

Harp traps (Fig. 2.) have vertical nylon strings – fishing line type stuff – that is strung vertically in two slightly offset rows. They are sited in areas where bats are likely to be foraging and are used in conjunction with an acoustic lure, which plays bat social calls. The lure elicits a territorial response in the bats and they fly toward the sound and then into the trap. The strings are set so they “absorb” the bat, causing its wings to fold, the bat then falls down into a pouch which has a two layers of plastic, one clear and one cream, which are set up so the bat can fall in but not fly or crawl out. The bat crawls into the space between the plastic as it is rather like being in a roost for them. The bats are then easily extracted by hand – much easier than mist nets so can be done by less experienced people.

Worcestershire Wildlife Trust gratefully acknowledges the financial support given to the project by the Peoples’ Trust for Endangered Species (PTES).

References

Harris, S.& Yelden, D.W. 2008 Mammals of the British Isles: Handbook. 4th Edition. Southampton: The Mammal Society.

Schofield, H. & Morris, C. 2000. Ranging behaviour and habitat preferences of female Bechstein’s bat, Myotis bechsteinii (Kuhl, 1818), in summer.Report held by The Vincent Wildlife Trust.

Sedgeley, J., Hitchcock, J. & Birks, J. 2012. The National Bechstein’s Bat survey and beyond. Worcestershire Record. 32:24-25.

Images

1. Excellent habitat for Bechstein’s Bat with mistnet.

2. Harp trap set in Grafton Wood.

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 13-19 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Coleoptera of note in the Kidderminster area, Winter 2011-2012

Alan Brown

Well, there was no let up in my survey recording last winter, all done within two miles of Kidderminster. I started off recording ladybirds and then I noticed certain beetles were still active during the winter months so I recorded those as well. Others I recorded hibernating and come the spring of 2012 I turned to some of our lesser known species, Silphidae, etc. Then in late spring I went back to saproxylic beetles and also began recording some interesting weevil species for the first time. I was quite amazed at how many different species I was recording compared with last year’s finds. My time searching suitable habitats was severely curtailed by the bad weather but I persevered and was rewarded beyond my expectations. To be able to observe these species active at night was really quite fascinating. My only disappointment is the fact that one of the most important habitats, namely hollowed out oak trees are almost non existent in the Kidderminster area: I saw only two. Nonetheless the results of the survey shows there is still a vast array of species to be found here. All the species listed were recorded at night and most have digital photos to match. The approximate body length is given for each species.

Fig. 01. Sphaeriestes castaneus (Salpingidae: local. 3 mm): 2.12.2011. This was the first winter active species that I came across. A predatory species that I only found on Scots Pine. This species appears to hunt alone but is very active and detected on branches looking for prey. Last individual was seen on January 21st.

Fig. 02. Rabocerus gabrieli (Salpingidae: notable B. 4 mm): 10.12.2011. Another predatory species. These were active throughout the winter, seen pairing up in early February and then disappeared soon after. I would sometimes find lone individuals on other types of tree, but usually came across this species on Silver Birch in groups up to a dozen situated near small bark beetle galleries. Last one seen on Feb 8th.

Fig. 03. Phloiophilus edwardsii (Phloiophilidae: notable B. 3 mm): 10.12.2011. A fungus beetle. I found these active throughout the winter months on decayed branches of oak trees, linked to the fungus, Peniophora quercina.Last seen on Feb 24th this species was found at three sites in good numbers around Kidderminster.

Fig. 04. Aplocnemus impressus (Melyridae :notable B. 5 mm) : 20.12.2011. The adult feed on pollen but the larvae are predatory feeding on various bark beetle larvae. Much more metallic than the photo suggests, I found this species hibernating usually in niches on birch trees but sometimes on Pine also.

Fig. 05. Rhizophagus nitidulus (Monotomidae: notable B. 4 mm): 21.1.2012. Another predatory species, I first saw active in numbers very early in the year on decaying Silver Birch trees linked to a colony of Xyloterus lineatus. This beetle is very good at slipping into small cavities. Occasionally I saw this species throughout the spring.

Fig. 06. Dorytomus ictor (Curculionidae: notable B. 5 mm): 8.1.2012. One of the catkin weevils, this species can usually be found active at night on Grey Poplar trees. I usually found this species on the trunks of mature trees very early in the year and others I found in the state of hibernation under Pine bark close by. This species can be seen throughout the year and appears to be doing well in Kidderminster.

Fig. 07. Anthribus nebulosus (Anthribidae: notable B. 3 mm): 22.1.2012. Unlike most other weevils this is one of two weevil species which are predatory, feeding on various scale insects, larvae parasitising ovipositing female scale insects. It is also restricted to Pine trees. I found a single specimen hibernating in a niche on the trunk of a mature Scots Pine. Very difficult to find and very small.

Fig. 08. Anthribus fasciatus (Anthribidae: notable A. 4 mm): 8.3.2012. This is the other predatory weevil which also predates various scale insects restricted to deciduous trees. I found four of these hibernating on an open roadside verge. Two were found in niches on a mature Lime and two others on a nearby Cherry tree. A quite colourful species.

Fig. 09. Hadrobregmus denticollis (Anobiidae: notable B. 6 mm): 8.3.2012. I found one of these behind decaying bark on the same old Cherry tree on the roadside verge. The beetle and larvae feed on dead wood and this species has also been linked to Hawthorn trees.

Fig, 10. Caenopsis fissirostris (Curculionidae:notable B. 6 mm): 7.4.2012. I saw two of these actively investigating some decaying bark near the base of a mature Beech tree at Hurcott wood. Most records for this species come from West Wales so it was a real surprise to see them in the Kidderminster area. I’ve not seen anymore since.

Fig. 11. Acalles ptinoides (Curculionidae:notable B. 3 mm): 7.4.2012. A small species associated with decaying wood on very old Chestnut stumps, I first recorded these in good numbers at Hurcott Wood and also in woodland alongside the Devil’s Spittleful Nature Reserve (NR). They are active throughout the spring and summer.

Fig. 12. Ptinus sexpunctatus (Ptinidae:notable B. 4 mm): 24.4.2012. A spider beetle usually associated with dead wood on deciduous trees, I find these occasionally on decaying Lime trunks and also on an old Cherry tree on a roadside verge.

Fig. 13. Aclypea opaca (Silphidae:notable A. 12 mm): 3.5.2012. I found a single specimen of the sugar beet beetle on the roadside verge opposite some arable fields. This herbivorous species is well known for its taste for sugar beet but also feeds on cereal plants and various seeding grasses. A beautiful species.

Fig. 14. Silpha tristis (Silphidae: local. 17 mm): 27.8.2011. The snail hunter. This is a true predatory species that also feeds on slugs and is rarely found in carrion traps. Also seems to prefer open sandy grassland areas. I found these in good numbers at Springfield Park but also on roadside verges and temporary arable meadows.

Fig. 15. Megatoma undata (Dermestidae:notable B. 6 mm): 23.5.2012. This species is usually found on dead wood feeding on dead insect remains. I found this specimen in open parkland in a niche on a healthy Ash tree next to a pile of decaying willow logs.

Fig. 16. Trichosirocalus barnevillei (Curculionidae:notable B. 2.5 mm):3.5.2012 A herb feeding weevil, I found a good number of these on Narrow Leaved Plantain on sandy, roadside grass verges and temporary arable meadows.

Strophosoma faber (Curculionidae:notable B. 6 mm): 3.5.2012.(no picture). A seed feeding weevil which is also found in sandy, dry habitats. I found these in good numbers on roadside grass verges on Narrow Leaved Plantain and Yarrow.

Fig. 17. Mesosa nebulosa (Cerambycidae RDB 3. 15 mm): 26.5.2012. This Longhorn beetle is an extremely difficult species to find due to its natural camouflage. It is usually found after falling from decaying oak branches in the uppermost reaches of mature oak trees. So I was lucky to find two of these on a decaying oak branch barely five feet from the ground. The secret in this case was to search a stunted, isolated old Oak tree. It was about fifteen foot tall with a wide canopy shading the decaying branches beneath. I found this one at Devil’s Spittleful NR.

Fig. 18. Mycetophagus piceus (Mycetophagidae:local. 4 mm): 27.5.2012. A nocturnal beetle found in various decaying oak situations relating to fungus. I found these on a very old oak bough although no fungus was seen. Quite a colourful species.

Fig. 19. Abdera quadrifasciata (Abderiidae:noteble A. 4 mm): 16.6.2012. I found this species also on decaying oak branches with crust fungi. Active at night on woodland fringe, Devil’s Spittleful NR.

Fig. 20. Scaphisoma boleti (Staphylionidae:notable B. 2 mm): 30.6.2012 [no picture]. Another species linked to decaying wood with fungus, I found two of these on white-rot fungus on a decaying oak log in open situation. Active at night at Devil’s Spittleful NR.

Fig. 21. Ernobius mollis (Anobiidae:local. 5 mm): 22.6.2012. This species is strictly linked to Pine. I found large numbers on a dead, standing Pine tree, I also found them on dead bark on healthy trees. Hurcott Wood.

Fig. 22. Symbiotes latus (Endomychidae:notable B. 5 mm.): 15.7.2012. A fungus beetle linked to fungus on dead wood, I found four of these on decaying heart wood on an oak with white-rot fungus, active at night. I also found these in wood detritus in the bottom of a hollowed-out oak. Confirmed by Paul Whitehead.

Fig. 23. Pediacus depressus (Cucujidae:notable A. 4 mm): 15.7.2012. Similar to Pediacus.dermestoides, but usually the head and pronotum of this species are bright red and the tooth on the pronotal hind-angles is more blunt. A predatory species I found one active at night on a dead standing Pine investigating a beetle gallery. Devil’s Spittleful NR

Fig. 24. Xyleborus dispar (Scolytidae:notable B. 3 mm): 21.7.2012. The European shot-hole borer. Until recently this species was listed as RDB 3, however this species now increasing its range. I found two of these looking over a recently cut, mature oak trunk at night. Its usual preference is for decaying oak related to fungus.

Fig. 25. Platypus cylindrus (Platypodidae:notable B. 5 mm): 21.7.2012. The Oak Pinhole-Borer has also become much more widespread. I saw plenty of these and the small telltale piles of white shavings on the same recently cut oak trunk.

Fig. 26. Odonteus armiger (Bolboceratidae:notable A. 10 mm): 21.7.2012. A scarab beetle which is very seldom seen, I found one female which is rather less spectacular than the male, on a sandy trail on heathland. This species is usually linked to subterranean fungi and also linked to dung. The female has the ridge running across the pronotum which identifies it. On the heath cattle have been grazing there for most of the year. Devil’s Spittleful NR

Acknowledgements

Thanks to John Meiklejohn whose identifications have been really appreciated and also to Paul Whitehead for some of the trickier identifications.

Images

Fig. 01. Sphaeriestes castaneus (Salpingidae: local. 3 mm): 2.12.2011.

Fig. 02. Rabocerus gabrieli (Salpingidae: notable B. 4 mm): 10.12.2011.

Fig. 03. Phloiophilus edwardsii (Phloiophilidae: notable B. 3 mm): 10.12.2011.

Fig. 04. Aplocnemus impressus (Melyridae :notable B. 5 mm) : 20.12.2011.

Fig. 05. Rhizophagus nitidulus (Monotomidae: notable B. 4 mm) :21.1.2012.

Fig. 06. Dorytomus ictor (Curculionidae: notable B. 5 mm): 8.1.2012.

Fig. 07. Anthribus nebulosus (Anthribidae: notable B. 3 mm): 22.1.2012.

Fig. 08. Anthribus fasciatus (Anthribidae: notable A. 4 mm): 8.3.2012.

Fig. 09. Hadrobregmus denticollis (Anobiidae: notable B. 6 mm): 8.3.2012.

Fig. 10. Caenopsis fissirostris (Curculionidae:notable B. 6 mm): 7.4.2012.

Fig. 11. Acalles ptinoides (Curculionidae:notable B. 3 mm): 7.4.2012.

Fig. 12. Ptinus sexpunctatus (Ptinidae:notable B. 4 mm): 24.4.2012.

Fig. 13. Aclypea opaca (Silphidae:notable A. 12 mm): 3.5.2012.

Fig. 14. Silpha tristis (Silphidae: local. 17 mm): 27.8.2011.

Fig. 15. Megatoma undata (Dermestidae:notable B. 6 mm): 23.5.2012.

Fig. 16. Trichosirocalus barnevillei (Curculionidae:notable B. 2.5 mm): 3.5.2012.

Fig. 17. Mesosa nebulosa (Cerambycidae RDB 3. 15 mm): 26.5.2012.

Fig. 18. Mycetophagus piceus (Mycetophagidae:local. 4 mm): 27.5.2012

Fig. 19. Abdera quadrifasciata (Abderiidae:noteble A. 4 mm): 16.6.2012.

Fig. 20. Scaphisoma boleti (Staphylionidae:notable B. 2 mm): 30.6.2012.

Fig. 21. Ernobius mollis (Anobiidae:local. 5 mm): 22.6.2012.

Fig. 22. Symbiotes latus (Endomychidae:notable B. 5 mm.): 15.7.2012.

Fig. 23. Pediacus depressus (Cucujidae:notable A. 4 mm): 15.7.2012.

Fig. 24. Xyleborus dispar (Scolytidae:notable B. 3 mm): 21.7.2012.

Fig. 25. Platypus cylindrus (Platypodidae:notable B. 5 mm): 21.7.2012.

Fig. 26. Odonteus armiger (Bolboceratidae:notable A. 10 mm): 21.7.2012.

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 11 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Haeterius ferrugineus rediscovered after 92 years absence

Alan Brown

On June 10th, 2012, a single specimen of the ant-associated Hister Beetle Haeterius ferrugineus was found at night in the nest of the slave maker ant Formica sanguinea in the Kidderminster area. This small (1.5-2.0 mm long) Hister Beetle, which is classed as being extremely rare, was last recorded on the Isle of Wight in 1920.

Description: Very small, about 2mm long, oval, bright orange-red in appearance with beautifully sculptured appendages and pronotal edges (Fig.1.).

Habitat description: Generally in the ant nests of Formica sanguinea and Formica fusca. In this case under a piece of oak wood in an open, sandy grassland terrain on a slightly south-facing slope. The beetle itself was observed moving in and out of a small section of white-rot fungus attached to the underside of the wood close to the ants’ larval chamber. A second ant specimen taken from the nest was identified as Lasius brunneus (the Tree Ant) but this may have been an accidental occurrence and will need further investigation before confirmation can be ascertained. The site is largely undisturbed and sun-exposed with a warm micro-climate which is perfect for the ants which is there in abundance.

History: Notes from Donisthorpe (1927).

“ … Haeterius ferrugineus , whose normal hosts are Formica fusca and Formica sanguinea, with fusca as slaves, was first captured in this country by E.W. Johnson,who found it with F. fusca and A. (C.) flavus at Hampstead in 1848, and subsequent years. In 1862 Power took it with F. sanguinea at Weybridge, and Douglas and Stott found it with the same ant near Croydon. Since then, so far as I know, it did not occur again until 1909 when Bedwell found it sparingly with F. fusca at Box Hill, where I subsequently took it with him. A single specimen which Stott found in an ants’ nest at Luccombe Chine, Isle of Wight, in 1920, is the only other record known to me. The host species was unfortunately not noted.”

Habits: This species is much more common on the continent than it is with us and is also found with far more species of ants. According to Donisthorpe (1927) it has been kept in captivity by Wasmann, Janet and others. Wasmann kept specimens alive in these nests for between 2-4 years and noticed their copulation, treatment by hosts, etc. The larvae are still unknown. The ants frequently lick the beetle, carry it about and play with it, sometimes very roughly. The beetle itself feeds on dead and wounded ants, ant larvae, pupae, and mites etc. Both Wasmann and Viehmeyer once saw the beetle being fed by its hosts although this was a very exceptional instance.

A second sighting of Haeterius ferrugineus in Worcestershire?

Two months after the initial find, on the night of 15th August 2012 I was busy doing a night hunt for Silpha beetles in the same area of grassland where I had seen the original Haeterius ferrugineus beetle. I ended up back at the same piece of wood and decided out of curiosity to have another look. The Formica sanguinea nest was larger than I had remembered it, with a large pile of pupa in the centre. For a few seconds I saw nothing but ants, but then from beneath the pupae I caught sight of the familiar orange-red glint of a Hister Beetle. Then from under more pupae another appeared and another, four all told. I couldn’t believe my luck. I waited until both Hister Beetles and ants had withdrawn deeper into the ground and then carefully re-laid the wood and left them to it. The site itself I have decided to keep secret but there is no reason not to believe that this species may exist in other sandy grassland sites around Kidderminster and perhaps also around the Wyre Forest where large colonies of the ant have been recorded. Could the beetle itself be under-recorded? Possibly, as all subterranean species are difficult to find and one relies to some degree of good fortune. Perhaps by laying out pieces of wood in suitable locations the species could be found more often, as the ant involved does seem to like building nests against decaying wood. I have also found the ant under Limestone slabs too, so possibly suggesting another way of finding the beetle without causing too much disruption to the ants nest.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks should go to Cristoph Benisch who kindly allowed me to use a photo from his excellent Coleoptera website www.kerbtier.de. Also thanks to Rosemary Winnall for supplying the literature from Donisthorpe (1927).

Editor’s Note: Genus name formerly spelt Hetaerius. The species is extremely rare or unrecorded: ‘Very local in S England (S Hampshire, Isle of Wight, Surrey and Middlesex); Rare’. (Duff 2012).

References

Benisch, Christoph. 2007-2012 www.kerbtier.de. The beetle fauna of Germany.

Donisthorpe, H. St. J. K. 1927 The guests of British ants, their habits and life-histories. Routledge, London.

Duff, A.G. 2012. Beetles of Britain and Ireland. Volume 1. Duff:West Runton, Norfolk.

Image

Fig. 1. Haeterius ferrugineus Picture copyright Christoph Benisch www.kerbtier.de.

Worcestershire Record | 33 (Nov 2012) page: 12 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Vine Weevil Otiorhynchus armadillo in Kidderminster

Alan Brown.

There’s an Armadillo loose in Worcestershire …

On the 26th of April 2012 a single specimen of the invasive Vine Weevil Otiorhynchus armadillo was found on Ivy at Springfield Park, Kidderminster. Close by, a large colony was found in the gardens of a new housing estate overlooking Puxton Marsh. Quite how long they have been established here is unknown but in South West London where they were first discovered in 1998 the species is now reaching pest proportions and it has officially become the most common weevil there.