Issue 30 April 2011

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 29-30 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

A Teme Valley moth-ing update

Danny Arnold, Chairman of the Teme Valley Wildlife Group

The Teme Valley is host to some of the most pristine and diverse habitat in Worcestershire. In fact, there are only but a handful of habitat types found in the County that are NOT found in the Teme Valley and environs. As such, the area abounds with bio-diversity in every aspect of flora and fauna. Yet, in reality, when it comes to biological recording, the Teme Valley, is very much, the forgotten corner of Worcestershire. As a way of emphasising this point, on the Lepidoptera front, the fourth ‘first record for Worcestershire’ has shown up in the Teme Valley in less than two years. Though concerted effort on two trapping sites, one each side of the Valley, four ‘new’ moth species have been recorded in the County for the first time.

In July 2009, at the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust’s Hunthouse Wood reserve the tiny 496a Coleophora adjectella was taken by Patrick Clement during a scheduled Teme Valley Wildlife Group monthly trapping session. Following genitalia dissection, Tony Simpson, the Worcestershire County Moth Recorder, accepted the specimen onto the Worcestershire County list. This moth is typically found in the south-east England where the main food plant is Blackthorn. MOGBI (Emmet 1996) indicates that continental authors also include Hawthorn and, interestingly, Wild Cherry, all of which are found in Hunthouse Wood.

Since that time the remaining ‘firsts’ have all come from the South side of the Valley at the writer’s constant effort site at Upper Rochford. In June 2010, a single specimen of the macro moth 2286 Light Knot Grass Acronicta menyanthids came into one of five Skinner traps being run on the site over night. With the habitat all wrong for this species, it being an upland/damp moorland feeder, it almost certainly found its way down into the Teme Valley from Clee Hill, from where it has been recorded in Shropshire. This moth is a definite ‘northern’ species with north Worcestershire being right on the edge of its geographical territory.

Less than a month later in July 2010, another suspected migrant off the Clee came to another of the five traps. This time it was the small ‘micro’ moth, 1008 Philedone gerningana. Once again, this is another upland/acid moorland feeder, having a very similar appearance to the far more common Light Brown Apple Moth which is found in the Valley. The main visual difference between the two being the bipectinate-ciliate antennae.

Then in mid January 2011, during a three night mild spell, which saw the first moths appear in the traps for several weeks, a small Tortrix moth came into a light trap. It was at first considered to be a form of Acleris hastiana, a moth of variable colouration and one of the very few micro moths on the wing at this time of year. However, not feeling ‘quite right’, it was genitalia determined to confirm yet another County first: 1059 Acleris abietana.

A.abietana was first located in the UK in the mid 1960’s where it is thought to have come in on firs from Scandinavia destined to be planted in Scotland. The NBN Gateway map shows just three records from around the Perthshire area and one close to Kielder Water. There is also known to be one additional record in 2008 from Herefordshire, which was the most southerly record for the species. Some sources infer additional UK records; though appear not to be necessarily publically documented. Never the less, this is certainly a UK scarcity, and again, an excellent record for the Worcestershire list.

It may be no coincidence that three of these four species are apparently right on the edge of their Southern geographical limit, with the forth being right at the North of its UK limit. And in all four cases the Teme Valley has the habitat to hold them.

In addition to these impressive finds during the last two years, the Teme Valley has also produced numerous 2nd and 3rd moth species records for Worcestershire, all going to emphasise the biological importance of this area in terms of specialist habitat diversity and its condition.

In 2011, the Group is looking to expand their moth trapping sites into totally unrecorded new habitats within the area. A circular request to the people on the Teme Valley Wildlife Group emailing list, came up with ten responses from around the Valley with permissions for new areas to trap.

The Teme Valley oozes with tiny tracts and parcels of land that have remained unspoilt and relatively untouched for many years and it is these that are going to be the focus of attention. We already know from the conservationists the importance of building ‘wildlife corridors’ for the long term protection of species. The Teme Valley is the living blue print!

Who knows what wildlife gems this area will bring forth in 2011?

What is certain is that this ‘forgotten corner of Worcestershire’, is slowly but surely putting itself on the map….literally!

Reference

Emmet, A. Maitland, (Ed). 1996. The moths and butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland. Volume 3, page 221. Harley Books.

Images

Fig.1. Light Knot Grass Acronicta menyanthids. Picture ©Danny Arnold

Fig.2. Philedone gerningana. Picture ©Danny Arnold

Fig.3. Acleris abietana. Picture ©Danny Arnold

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 28-29 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Note on Pauper Pug Moth Eupithecia egenaria

Danny Arnold

The Pauper Pug Moth is a relative rarity within Worcestershire and indeed, much of the country. First found in Worcestershire as recently as 2000, the main stronghold has been at Shrawley Wood where they have shown up in good numbers. Until recently this has been the only site in the county where this species has been recorded (bar a single individual which was captured and identified from the side of the Malvern Hills in 2010).

On a trapping session in early May 2011, Danny Arnold & Dean Fenton discovered a hitherto unknown and new strong population of this Red Data Book species at a Hanley Dingle, one of the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust’s more difficult to access sites. Several dozen were caught in the two moth traps set up, along with a host of other ‘new moth records’ for the site. Identification was confirmed by dissection of both a male and female.

The Pauper Pug larvae are a Lime Tree feeders and Hanley Dingle supports both Large & Small leaf Limes.

(Comment. This moth was first discovered in Britain in 1962 in the Wyre Valley limewoods. (Riley, A.M. & Prior, G. 2003. British & Irish Pug Moths. Harley Books). There seems to be some discussion on whether the larvae feed on small-leaved or large-leaved lime. Hanley Dingle contains both species and the largest stand of large-leaved lime in Worcestershire). Shrawley Wood is of small-leaved lime. Limes are widespread in west Worcestershire. (Ed)).

Image

Fig. 1. Pauper Pug Moth Eupithecia egenaria from Hanley Dingle. Picture ©Danny Arnold

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 26-28 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire and the new Dragonfly Atlas of England, Wales & Scotland

Mike Averill

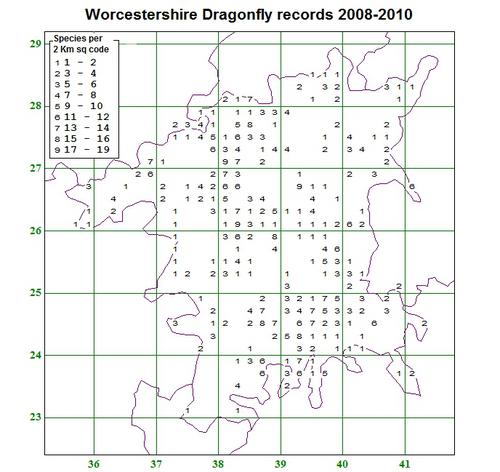

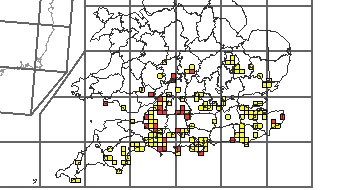

2010 was the third of a five year project to remap the dragonflies in the UK mainland. In Worcestershire 884 new records were added to the previous two years to give 2751 in total.

The results from the first three years in Worcestershire are summarised in the map (Fig. 1.). This shows how many species have been recorded in each 2×2 km square and the total is coded into nine groups as per the key. It shows that many squares have only two species or less recorded which is obviously an underestimate of the real situation. There are a few sites coded to nine which means there are between 17 and 19 species for example the Grimley gravel pits and Upton Warren. If possible recording in the blank areas is needed as the popular sites are well covered.

In 2010 new records helped to fill in some of the outlying areas around Tenbury and the old South Birmingham part of the vice county, but there are still large gaps in quite a few locations such as in the SW of the county and in SO97.

To see which species are under-recorded check the species listed in the table below against the 10×10 km squares. The table is set in two parts to cover all species.

| Aeshna cyanea | Aeshna grandis | Aeshna juncea | Aeshna mixta | Anax imperator | Calopteryx splendens | Calopteryx virgo | Coenagrion puella | Cordulegaster boltonii | Enallagma cyathigerum | Erythromma najas | Erythromma viridulum | Gomphus vulgatissimus | |

| SO56 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||

| SO66 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 1 | ||||||

| SO67 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| SO73 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| SO74 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| SO75 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| SO76 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| SO77 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 7 | ||

| SO83 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | |||||

| SO84 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 15 | 2 | 11 | 32 | 8 | 5 | ||||

| SO85 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 19 | 8 | 1 | 19 | 23 | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| SO86 | 8 | 7 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 16 | 24 | 33 | 15 | 1 | |||

| SO87 | 23 | 26 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 22 | 3 | 45 | 22 | 16 | 1 | 1 | |

| SO88 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 11 | |||||

| SO93 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 22 | 6 | 3 | 19 | 32 | 3 | ||||

| SO94 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 111 | 8 | 24 | 48 | 8 | 2 | 15 | ||

| SO95 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | ||||

| SO96 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 10 | 39 | 15 | 21 | 14 | 3 | ||||

| SO97 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||

| SO98 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| SP03 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| SP04 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| SP05 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| SP06 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||||||

| SP07 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 3 | ||||||

| SP08 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| SP13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| SP14 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| SP16 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||||||

| SP18 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 127 | 112 | 10 | 84 | 156 | 251 | 71 | 244 | 5 | 288 | 89 | 10 | 33 |

| Ischnura elegans | Lestes sponsa | Libellula depressa | Libellula fulva | Libellula quadrimaculata | Orthetrum cancellatum | Platycnemis pennipes | Pyrrhosoma nymphula | Sympetrum danae | Sympetrum fonscolombii | Sympetrum sanguineum | Sympetrum striolatum | Total | |

| SO56 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 15 | |||||||||

| SO66 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 60 | |||

| SO67 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 37 | |||||||

| SO73 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| SO74 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 21 | |||||||

| SO75 | 3 | 5 | 16 | ||||||||||

| SO76 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 41 | ||||||

| SO77 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 82 | |||||

| SO83 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 67 | |||||

| SO84 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 23 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 25 | 198 | ||

| SO85 | 36 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 16 | 194 | |||

| SO86 | 37 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 17 | 1 | 6 | 22 | 269 | ||

| SO87 | 50 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 34 | 1 | 9 | 36 | 342 | ||

| SO88 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 16 | 86 | ||||||

| SO93 | 29 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 17 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 184 | ||

| SO94 | 69 | 3 | 9 | 26 | 3 | 16 | 54 | 33 | 1 | 32 | 503 | ||

| SO95 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 71 | |||

| SO96 | 30 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 20 | 260 | ||

| SO97 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 35 | |||||||

| SO98 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 30 | ||||||||

| SP03 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| SP04 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 68 | ||||

| SP05 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20 | ||||||||

| SP06 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 42 | ||||||

| SP07 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 62 | ||||||

| SP08 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||

| SP13 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| SP14 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| SP16 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 23 | |||||||

| SP18 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||

| 376 | 27 | 70 | 39 | 57 | 131 | 107 | 169 | 2 | 5 | 56 | 232 | 2751 |

Table shows the number of records for each species per 10×10 km square in Worcestershire for 2008-10

Please send your records to mike.averill@blueyonder.co.uk and these should contain at least the basic information about the location of the dragonfly with an NGR, date and species, but if you can give any estimate of numbers or breeding activity that would add a lot to the record. If you feel keen I can send a spreadsheet with a pick list of species already entered.

If you travel outside Worcs, don’t forget this work is part of a national atlas and all records are welcome. I am happy to receive any records or you can enter them online via the British Dragonfly Society website: http://www.ghmahoney.org.uk/bds/recording/recordentry.aspx

Records from Herefordshire are badly needed to bring the dataset up to date.

Image

Fig. 1. The number of records of dragonflies in Worcestershire for each 2×2 km square (see code) collected in the first three years of the project.

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 9-15 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Mistletoe and mistletoe insects, overview and observations from 2010

Jonathan Briggs – including pictures © unless otherwise stated.

jonathanbriggs@mistletoe.org.uk

This account of mistletoe Viscum album and its associated insects reprises and updates the account I gave to the Worcestershire Recorders Annual meeting in March 2010. The text draws heavily on a recent paper I wrote for the Gloucestershire-based CNFC (Briggs 2011) with some updated observations from this winter. Hopefully it will stimulate more mistletoe bug, moth and weevil hunting in Worcestershire this summer; our mistletoe insects are an interesting little group, most are (relatively) easily spotted, and there should be plenty of them in Worcestershire.

I’ll start with a quick review of mistletoe itself, with notes on its distribution, hosts and habitats, as understanding those is essential if the invertebrates are to be fully appreciated.

Mistletoe distribution

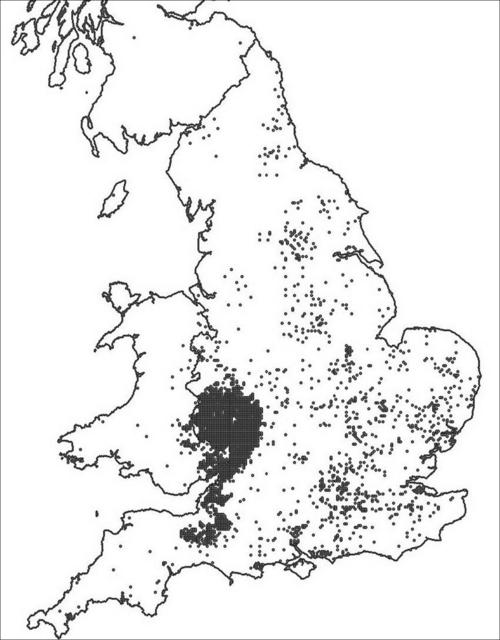

Britain is at the northern edge of mistletoe’s distribution in Europe, with mistletoe occupying slightly more northerly latitudes here than it does in mainland Europe (it is almost entirely absent from Scandinavia). This suggests a climatic limitation to its natural range – a concept supported by a brief glance at its UK distribution where there is a clear bias to the SW Midlands area.

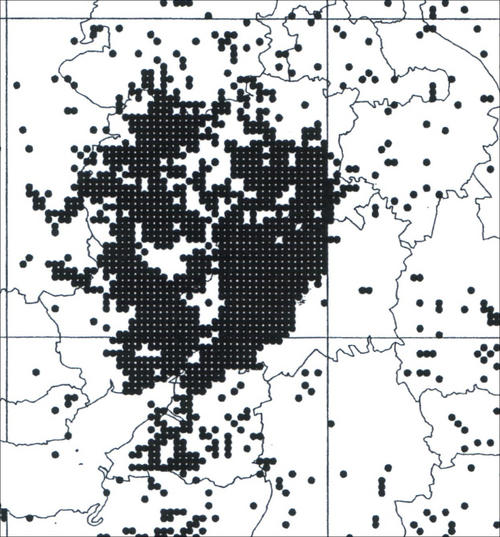

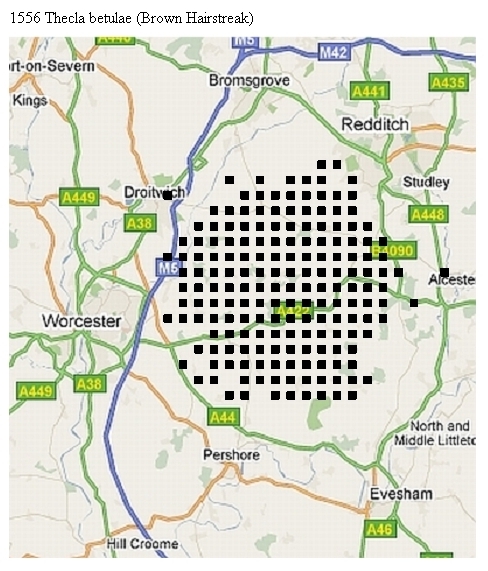

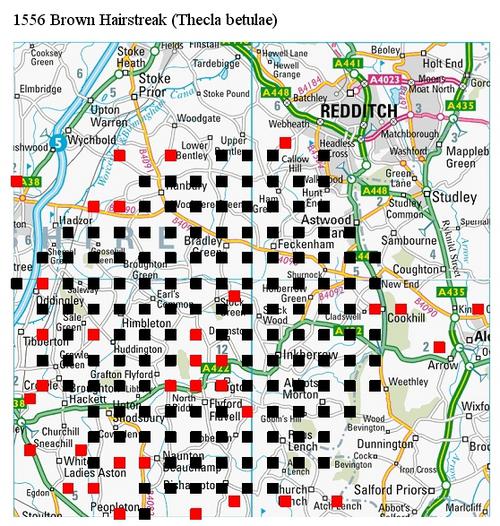

Within Britain this distribution is often simplified as being the ‘Three Counties’ of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire and is often assumed to be a result of association with apple orchards. But looking at an enlargement map (both maps are derived from the BSBI/Plantlife 1990s national mistletoe survey) it becomes clear that the distribution more closely matches the lowlands in and around the river corridors of the Severn, Avon, Wye and Usk, straying well into Gwent and down into Somerset. Obvious geographical constraints seem to be altitude – the Cotswold escarpment clearly forms the eastern boundary, with the southern Welsh uplands forming the western side and the Clee Hills and the Birmingham plateau forming the northern limit.

This distribution has been known, and commented on, throughout botanical recording history, but exact climatic factors are difficult to define, though it is thought that winter and summer temperature maxima and minima are important. But, as the maps show, the species can survive almost anywhere in southern Britain, so it’s obviously not quite so simple. There are, incidentally, several relatively new accounts of some of the eastern counties’ mistletoe colonies spreading further in recent years, so something may be changing (some possible factors are discussed briefly below).

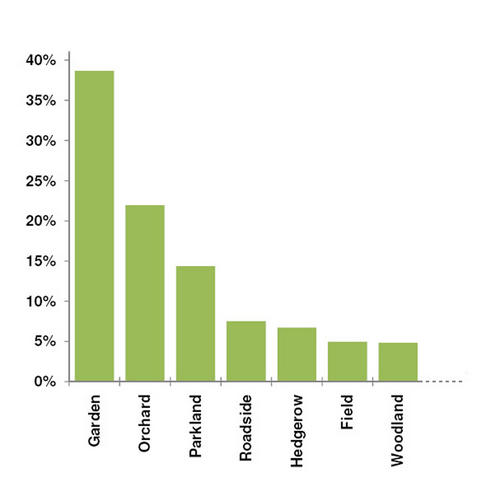

Habitats and hosts

The habitat and host preferences of mistletoe are just as peculiar as its distribution. As a parasite of tree branches the species is, obviously, dependent on suitable host trees for its survival, but it really requires those trees to be in fairly open habitats, and it does not thrive in a woodland environment. In a pre-clearance Britain it would probably have been restricted to trees on edges of clearings, alongside rivers and on the open habitats of steep slopes. In our more man-made Britain the vast majority is found on trees in gardens, orchards, parks, churchyards, field margins and roadsides. The implication is that it would be much less frequent without these habitats, though its distribution might well be similar.

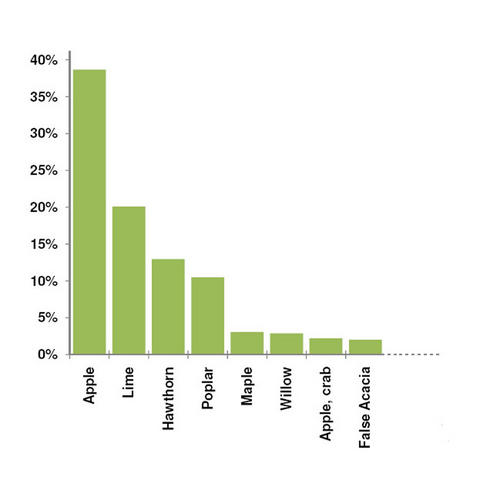

The pattern of preferred hosts is intriguing, with most mistletoe on man-made hosts (i.e.hybrids and varieties created through horticulture). Cultivated apple and hybrid limes support most of our mistletoe – choices which correlate quite well with the garden, orchard and parkland habitats. This host preference is marked, with huge proportions on those few tree species, but it is worth stressing that mistletoe will grow on many hundreds of different hosts too. Its natural (pre-clearance) hosts would probably be dominated by hawthorns, whitebeams, and white willows.

Conservation issues arising so far

The association of mistletoe with apples, orchards and the three counties has inevitably led to a strong belief that these are all interlinked, and that the future of mistletoe depends on the future of apple orchards. This is an oversimplification, but it is an important factor.

The 1990s BSBI/Plantlife Mistletoe Survey set out to investigate whether mistletoe was actually threatened by apple orchard loss. Results showed that whilst mistletoe quantity might be reduced through loss of orchards, the distribution of mistletoe was much the same as it had ever been, with possible increases in some areas. The ‘core’ area in the south-west midlands did however have the greatest range of hosts and habitats for mistletoe –its habitat preferences become even more dominated by gardens and parks further east, north or south.

This all tends to strengthen the view that it is here because the location suits it, not because there are/were lots of apple trees. An additional point of course is that apple growing areas occur, or used to occur, in many other parts of the country, but these other apple areas have no significant association now, or historically, with mistletoe.

The whole mistletoe conservation issue is, therefore, a little confusing. It is undoubtedly rare over most of Britain, and it is locally threatened in some areas. In those areas (primarily in the east) several local Biodiversity Plans have included direct action (e.g. deliberate planting) to encourage mistletoe. In other areas (again mostly in the east) it is reported to be locally increasing, apparently without intervention.

But here in the SW Midlands it seems to be still common, and there is no real threat to its continuing existence in the wider countryside. Except in orchards. And that’s where most of it is, in terms of quantity. Orchard loss is continuing despite many local campaigning groups raising awareness. Their efforts can save exemplary farm and community orchards but the loss in the wider countryside has either happened or is continuing.

This implies that we have already, and probably will continue to experience for the next few years, a reduction in the amount of mistletoe. Does this matter or not? In economic terms it might, as most Christmas mistletoe is harvested from orchards. The famous mistletoe auctions at Tenbury Wells are supplied almost entirely from apple orchards. So we seem likely to have a smaller mistletoe crop in future.

But the Tenbury mistletoe auctions always seem to have plenty of mistletoe – so is the crop really threatened? This is another confusing area, and there are no statistics to help, but it does seem reasonably likely that the auctions are being largely supplied by excessive growths of mistletoe in now-neglected orchards. In other words there might be a short-term glut of mistletoe available from older, senescent orchards, which makes current availability seem good. But this is an unsustainable situation – once those old trees have gone the harvestable quantities will surely reduce.

Conservation issues for associated species

So there might be some economic impacts for mistletoe cropping with continuing local apple orchard loss. What are the wider conservation implications? Loss of abundance might ‘only’ be a landscape issue in simple conservation terms, as long as the species remains common on other hosts and habitats locally but there may be some side-effects, particularly for the obligate insects, and the specialist birds, of mistletoe. The current, but ephemeral, phenomenon of excessive mistletoe growth on older apple trees may also have implications for these species.

The obligate insects of mistletoe are an odd little group. In the 1990s just four species were known in the UK, all overlooked and considered scarce or rare. Since then two more have been discovered (both by National Trust survey teams) and there may be more to find in future (several dozen are known from Viscum album in mainland Europe).

Their national status, and conservation needs, have only recently been given any attention, helped along by the attention given to mistletoe following the 1990s studies and the inclusion of one of them, the moth Celypha woodiana, on the UK BAP Priority Species list in 2008. But despite this recent attention, little is known about their biology as, inevitably, most recording is just that, recording. So there is much potential for investigation (and more recording too) particularly in terms of habitat and life-cycle needs. Do these insects thrive best on crowded mistletoe? Or on well-spaced clumps? Will a loss of abundance, with inevitably increased isolation of some colonies, be a problem or not? Is there a preference for male or female mistletoe? Older or younger plants? Edge-grown plants on the ends of tree branches, or denser growths further inside the canopy? And, not least, is the pre-occupation with sampling mistletoe on apple trees (where mistletoe is relatively accessible) resulting in flawed assumptions that these species are ‘associated’ with apple orchards, when they might be as common, or even more frequent, on mistletoe in other hosts/habitats?

A summary of each of the six species, drawn from my recent CNFC account (Briggs 2011), so with a bit of a Gloucestershire bias, is presented below. (Note that this is not a full assessment of current records.)

The six species are; one moth (the Mistletoe Marble Moth Celypha woodiana), three sap-sucking bugs (Cacopsylla visci, Pinalitus viscicola and Hypseloecus visci,), one predatory bug (Anthocoris visci – it feeds on the other bugs) and one beetle (the Mistletoe Weevil Ixapion variegatum). There are also several non-obligate insects using mistletoe too – I’ve added some points on pollinators to this account.

Celypha woodiana (Mistletoe Marble Moth)

This small tortricid moth was originally discovered in 1878 by John Wood of Tarrington near Hereford. It was known to be associated with apple orchards, but its larval food plant remained unknown until it was found to be a leaf-miner of mistletoe leaves in 1892.

The moth remained fairly obscure, with only occasional records across Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Gwent, Somerset, and Warwickshire, until it was added to the UK BAP in 2008. This has led to considerably more attention, with a 2009 national survey undertaken by Butterfly Conservation, part-funded by the National Trust and Natural England.

Finding the moth itself is difficult (though it does come to traps) so most survey effort concentrates on spotting the leaf-mines of the larvae. These begin as small comma-shapes, following hatching in late summer, and remain unchanged throughout the winter. In spring and summer they expand to a larger blister mine that can be spotted from the ground. This takes practice, as James McGill, who undertook the 2009 survey (McGill, 2009) found out. As part of that project he organised training sessions for others, showing how to look for these mines with binoculars.

McGill also reports on the difficulty of differentiating other tortricid moths that may be seen on or near mistletoe. Most are web-spinning, binding leaves together, but confusingly, Celypha can also sometimes spin leaves together, so larval appearance sometimes has to be used too.

McGill concentrated on apple orchards, visiting 34 sites across mistletoe’s core area. Several new sites were found, but some old sites failed to produce records. Of all the sites visited the best, in terms of number of host trees showing signs of the moth, was an orchard at Sandhurst, Gloucester, with the moth found on mistletoe in 10 trees.

The preoccupation of the 2009 survey with apple orchards is unsurprising but also slightly frustrating, as it would be useful to see whether the moth is as common on mistletoe on other hosts. Recording effort has always been biased towards orchards because of the original 1878 association with orchards, and the ‘official’ description of the moth in Bradley et al (1979) stating it is ‘apparently restricted to old apple orchards in the west of England’.

Some records from the 2009 survey hint at the importance of other hosts; the highest number of actual mines seen on one host tree during the survey was 27, on a hawthorn on the Somerset Levels. The most mines seen on apple were just 10, with most scoring well below that.

Other recent records give further information. There are Worcestershire records on mistletoe on Rowan (Simpson 2005). Further south in Gloucestershire Robert Homan has been recording it on mistletoe on hawthorn at Chaceley (Homan 2007), and also on hawthorns along the banks of the Coombe Hill Canal (2005 to 2010) and on hawthorn in Hyde Lane, Cheltenham (2005 to 2007).

It does seem likely that other mistletoe hosts may be just as important as apple orchards, and possibly more so. McGill noted that there seemed to be more mines on higher mistletoe growths, on the edges of the host tree. Most mistletoe outside orchards is in exactly this position, so if the moth prefers mistletoe like that, it must surely find a lot of potential in non-orchard trees. Of course there is undeniably more mistletoe in orchards, and so greater potential for the moth, but McGill also suggests that orchards with too much mistletoe seemed to have fewer moths; another hint that mistletoe in the wider countryside might be just as important.

Cacopsylla visci (Psylla visci)

This psyllid seems to be the most neglected of our mistletoe insects, partly because it is similar to so many others (e.g. Psylla mali, a specialist on apple). It has been recorded from across mistletoe’s core area, with records suggesting it is almost always found if it is actually looked for. Hollier & Briggs (1999) looked for it and recorded it in at all sites when sampling in Painswick, Kemerton and Little Marcle. Green & Meiklejohn (2000) found it readily at Little Comberton, and Price (1987) found it easily when looked for in Warwickshire.

Though often assumed to be limited to ‘our’ area it is surprisingly widespread, and has been recorded across the country (e.g. Badmin (1985) bred large numbers from mistletoe that had fallen from a Field Maple near Sittingbourne). More intriguingly it has recently been recorded as a new Norwegian species, despite only one sizeable mistletoe population within Norway (Hansen & Hodkinson, 2006). This raises the interesting question of how the species can spread to such an isolated population of its foodplant.

Pinalitus viscicola (Orthops viscicola, Lygus viscicola)

There’s an interesting recorder-challenge back-story for this one, which also links to the Hypseloecus (see below). In 1888 two new species of mistletoe bug were described from apple orchards near Paris, and Douglas (1889a) challenged British entomologists to find them. The Woolhope Naturalists Field Club in Herefordshire rose to this challenge and managed to describe one of the two, Pinalitus viscicola, as ‘common’ by the summer of 1889 (Douglas 1889b). They did not (then) find the other species.

At the same time, also in response to the challenge, previously collected but hitherto unidentified specimens of this species from mistletoe in Dorset and Norwich were also reported (Douglas 1889c). The implication was clear; this species had been overlooked, but was actually surprisingly common on mistletoe.

Today this little bug is still under-recorded, but still easy to find. Most records mention it as ‘frequent’. For example Hollier & Briggs (1999) found it in large numbers at Painswick, Kemerton and Little Marcle, and Price (1987) found it easily on mistletoe in apple in churchyards, allotments and gardens in Warwickshire. It occurs outside of mistletoe’s core area too; Nau (1985) recorded it from mistletoe on a Field Maple in Bedfordshire.

My own observations in 2010, at various sites in the Haresfield area of Gloucestershire suggest it is very abundant, with instars becoming very obvious from mid-May onwards, and numerous mature adults from early June, with a second flush of adults in late August and September.

The species overwinters as eggs, with instar development in spring, so it seems likely my second flush was a second generation that had matured quickly in June-July. Having found that this is a surprisingly easy species to find and monitor I hope to do some more detailed monitoring this season.

Anthocoris visci

This is the oddest of our mistletoe obligates, for it is a predatory species. It obviously does not rely directly on mistletoe, and instead is assumed (though with little actual evidence) to specialise in feeding on the other mistletoe bugs, especially the psyllid.

It was described as a new species by Douglas (1889d), after being collected from mistletoe near Hereford. Adults appear in August to September and are thought to overwinter under bark and lay eggs in spring. The larvae, said to be a distinctive orange-red, are also carnivorous. The adult also has some red colouring, but in general appearance is very similar to other Anthocorid bugs (the so-called Flower Bugs) and so it can easily be confused with other, commoner, species. In 2010 I observed several Anthocorids on mistletoe, including some feeding on psyllid bugs, but none were quite right for A.visci.

It is officially listed as ‘Notable’ with threats listed as destruction of old apple orchards. This is despite little knowledge of it on mistletoe outside apple orchards. Most records are in the mistletoe core area but it has also been spotted as far afield as Dorset, Denbigh and Norfolk. Like the other bugs it is fairly easily detected when looked for by experts but that isn’t very often, possibly due to lack of opportunity; Nau (1985) recorded it from mistletoe from the top of a poplar tree, but he could only sample that because it blew down in a gale.

Hypseloecus visci

This is second of the two species discovered near Paris in 1888 Douglas (1889a), but this is the one the Herefordshire naturalists failed to find in 1889 (see Pinalitus viscicola above). It may have been here all along, or may be a new arrival, but it wasn’t actually found in Britain until 2003, when the National Trust Biological Survey team found it in Somerset (Gibbs & Nau 2005).

The NT team found it on mistletoe in apple orchards in late July at two Somerset sites. Records since have been sporadic but scattered, and they include ‘large numbers’ taken on mistletoe in Bushy Park, Middlesex and ‘large numbers’ attracted to a moth trap in Hampshire (Denton 2004 and Gibbs & Nau 2005).

These latter observations suggest a wide geographic spread, well beyond the core area, and early confirmation on a variety of hosts (at Bushy Park the mistletoe is on limes and hawthorns, not apple). It is not at all clear whether this is a recent arrival or not but it certainly seems widespread. In 2010 I observed several bugs looking very like Hypseloecus visci on mistletoe in Gloucestershire sites but these were formally identified.

Ixapion variegatum

This is another new arrival, or at least a new discovery, first recorded in Britain in 2000 by the National Trust team on mistletoe on apple at Brockhampton, Herefordshire. It has subsequently been recorded in Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and Monmouthshire.

As with Hypseloecus visci we have no real knowledge of whether this is a new arrival or not. Foster et al (2001), describing the new discovery in 2000, suggest that this species is probably ‘a long-established but overlooked representative of the British fauna rather than a recent arrival’. It is a very small weevil, about 3mm long, so could be easily overlooked. On the other hand it is very distinctive, so if found should surely have been readily spotted as unusual.

Foster et al (2001), reviewing European data for this species, suggest that it occurs at low densities (easily missed?) and appears to increase when mistletoe is perhaps under stress, perhaps on host trees that are dying. This association with ‘stressed’ mistletoe is also reported by others (e.g. Green & Meikelejohn 2004).

My own observations in the Stroud area in 2010, summarised in the table below, suggest that the species is very easy to observe in mistletoe without beating, and so it should be relatively easy to find and to study. Some populations I found were very numerous. Furthermore, rather than choosing stressed mistletoe, the weevil seemed to be, in effect, the causeof the stressed mistletoe. Eggs are laid into mistletoe stems just below the terminal bud (which, by late summer, is next year’s flower bud), and the larva develops within the stem before emerging as an adult later in the summer. One particular mistletoe clump I observed started the year looking healthy, but with nearly all its terminal buds dying after weevil infestation, was looking very stressed by August.

Over the winter I noticed that some of the dead terminal buds did not, yet, have an exit hole. Dissection of these revealed a fairly mature sized larva within the stem, presumably overwintering and due to emerge in spring.

| Dates/period | Comments | |

| Adults present | 25th June to 9th September | Continually present at one or more of the sites visited |

| Mating observed | 2nd July, 22ndand 26thAugust | |

| Feeding observed | July to August | Probing/feeding stems, and leaves, resulting in a speckling of small brown dots on the leaf surfaces |

| Egg-laying | Assumed in early July | Not definitely observed, but adults probing around areas below terminal buds assumed to be preparatory to egg-laying |

| Adult emergence | June onwards | Exit holes observed in increasing numbers from June. Most single, a few double. Observed in vitro by taking distressed but intact shoots indoors – emergence occurred within 2 days. |

| Die-back of infested terminal buds | June onwards | Some distress to terminal leaves and buds observed before holes appeared – the degree of dieback increased after emergence. Most buds with dieback showed an emergence hole by August. Dieback in new season growth observed in August, implying development of second generation. |

| Overwintering larvae | Investigated in February | A few dead terminal buds without an exit hole were dissected, and a mature-size larva found. |

The weevil’s impact on terminal buds isn’t necessarily just a curiosity. It may imply that these weevils do not ‘require’ stressed mistletoe, as assumed by some recent authors. Some suggest that this ‘need’ makes a management case for retention of stressed (ie old, senescent,) mistletoe on overgrown apple trees. But that might not be the case at all. It also has implications for the argument over whether the weevil is native and overlooked or a new, spreading, arrival. If the latter is true then we might, perhaps, be seeing the spread of a damaging species, which is destroying mistletoe flower buds and so could have economic impacts for the mistletoe trade.

Pollinators

Mistletoe is an early flowering species, with flower buds (those terminal buds damaged by the weevils) developing in late summer, ready to open in February. Male and female flowers are produced on entirely separate plants, though they sometimes grow in such close proximity (sometimes one is epi-parasitic on another) that it seems like one growth exhibits both sexes.

Despite being small and green these flowers are insect-pollinated. The exact species are, not surprisingly, rather poorly documented, but if you visit a mistletoe-laden tree on a sunny day in February or March you will always see insect activity, mostly small flies (Dasyphora etc) around the flowers. Sampling is difficult unless they are low growths.

Bees, including honey bees, also visit the flowers, and this is especially noticeable in mistletoe-rich orchards where there are also bee hives. It is not known how significant this early resource is for insects but it would be interesting to gain more information on the pollinators. Too late now for 2011, but a challenge for 2012?

Scarcity v obscurity

As well as the insect habitat requirement questions mentioned above, the most obvious question for the insects is are they really scarce/rare, or are they simply overlooked? Only much more recording effort can answer this. Some (notably Cacopsylla and Pinalitus) seem common when looked for, so rarity for them at least might not be an issue.

The biggest problem for recording is, of course, access. Most mistletoe grows too high to be sampled. Which is why there is that apple orchard bias in the records. We really do need more recording from mistletoe outside orchards, and on all hosts. Gardens are a good starting point – most garden mistletoe is easily accessible, and though much is on apple there is also plenty on other hosts, particularly other rosaceous shrubs and trees, but also many others like Acer, Salix, or even oddities like Robinia. Understanding how these insects use mistletoe in the wider environment may be particularly important as apple orchards continue to decline.

Associated birds and climatic factor

Lastly, it’s worth a quick mention of mistletoe’s bird vectors, and briefly comment on review climate change issues.

The single (but often polyembryonic) seed in each mistletoe berry can only distributed by birds, and not many species of birds take an interest in them. The white, extremely sticky, berries are either overlooked (not being red, blue or black) or are disliked (because of their stickiness) by most birds. Only some thrushes, primarily Mistle Thrushes (Turdus viscivorous) and a few other relatively unusual species (e.g. Waxwing Bombycilla garrulus) take them regularly. The thrush usually swallows a lot of berries before excreting the seeds, still in a sticky slime. This string of seed-laden slime will stick onto a host branch and any seed that is contact with the branch can germinate. But most seeds end up dangling in the slime string and won’t survive.

The dynamics of this situation have been changing in recent decades with increasing number of overwintering Blackcaps, Sylvia atricapilla, across southern Britain. Blackcaps are another mistletoe specialist, but they are much more efficient than Mistle Thrushes as they only swallow the berry skin and pulp, wiping every seed off their beaks individually. This means that a lot more mistletoe seeds are being planted directly onto a host branch – which must, surely be affecting mistletoe spread. There are no data on this of course – it would be very difficult to monitor, and even more difficult to prove cause and effect – but there must be some impact.

The reports of faster spread in some eastern mistletoe populations might, possibly, be linked to Blackcaps, or even to other bird vectors (flocks of feral Ring-necked Parakeets have been seen feeding on mistletoe berries in the Richmond area of London, one of the areas where mistletoe is said to be increasing). Or this could suggest some climate change factors (the overwintering Blackcap increase might be climate-related). The longer-term impacts of climate change on our mistletoe may be rather more abrupt – Jeffree & Jeffree (1996) suggest climate change will eliminate mistletoe entirely from Britain, (though it may move north in mainland Europe) if UK winter temperature rises are greater than UK summer temperature rises. This will take a while of course – so there should still be plenty of time to get out there and document those mistletoe insects!

References

Bradley J. D. Tremewan, W. G & Smith, A. 1979. British Tortricid Moths: Tortricidae: Olethreutinae. The Ray Society London.

Briggs, J. 1996. Mistletoe – distribution, biology and the National Survey, British Wildlife 7(2), 75 28

Briggs, J. 1999. Kissing Goodbye to Mistletoe? BSBI and Plantlife Report

Briggs, J. 2011. Mistletoe (Viscum album); a brief review of its local status with recent observations on its insect associations and conservation problems, Proc Cotts Nat Field Club, XLV (II), 181 193

Denton, J. 2004 Heteroptera News 4 (Autumn 2004), 5

Douglas, J. W. 1889a. Two new species of Hemiptera on mistletoe Ent Mon Mag 25; 256

Douglas, J. W. 1889b. Lygus viscicola in England Ent Mon Mag 25; 396

Douglas, J.W. 1889c. Lygus viscicola Ent Mon Mag 25; 457

Douglas J. W. 1889d. A new species of Anthocoris Ent Mon Mag 25; 426

Foster, A. P., Morris, M. G., & Whitehead, P.F. 2001. Ixapion variegatum(Wenker), (Coleoptera, Apionidae) new to the British Isles, with observations on its European and conservation status, Ent Mon Mag 137; 95-105

Gibbs, D. & Nau, B. 2005. Hypsoloecus visci (Puton) (Hemiptera: Miridae) a mistletoe bug new to Britain, Br J Ent Nat Hist, 18; 159-161

Green, H. & Meiklejohn, J. 2000. Mistletoe Bugs Worcestershire Record 9: 23

Green, H. & Meiklejohn, J. 2004. Mistletoe Bugs and a weevil: Ixapion variegatum in Worcestershire. Worcestershire Record 17: 24-25

Hansen, L. O. & Hodkinson, I. D. 2006. The mistletoe associated psyllid Cacopsylla visci in Norway. Norw J Entomol 53; 89-91

Hollier, J. & Briggs, J. 1999. The specialist Hemiptera associated with Mistletoe Br J Ent nat Hist 12; 237-238

Homan, R. 2007. A record of the mistle leaf-miner Celypha woodiana in VC37 Worcestershire. Worcestershire Record 22: p22

Jeffree, C. E. & Jeffree, E. P. 1996. Redistribution of the potential geographical ranges of mistletoe and Colorado beetle in Europe in response to the temperature component of climate change. Funct Ecol 10; 562–577

Lane, S 2009. Recent records of Ixapion variegatum (Wencker) in Worcestershire and Gloucestershire. Beetle News 1(3); 3

McGill, J. 2009. Survey for the Mistletoe Marble (Celypha woodiana) in 2009 Butterfly Conservation Report No S09-29

Nau, B. 1985. Mistletoe Bugs, Het Study Group Newsletter 6: 8

Price J. M. 1987. Mistletoe Bugs in Warwickshire Het Study Group Newsletter 7: 5

Simpson, Tony 2005. Celypha woodiana, a rare and localised insect to look out for. Worcestershire Record 19; 18-19.

Images

Fig. 01. National distribution of mistletoe. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 02. Main area of Mistletoe distribution centred on the lower Severn valley. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 03. Mistletoe habitats. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 04. Main mistletoe hosts. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 05. Apple tree with a very heavy growth of Mistletoe. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 06. Celypha_woodiana__Mistletoe_Marble_moth_.Ray_Barnett

Fig. 07. Celypha woodiana (Mistletoe Marble moth) mine in Mistletoe leaf. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 08. Celypha woodiana (Mistletoe Marble moth). Searching for mines. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 09. Pinalitus viscicola (other names Orthops viscicola and Lygus viscicola). ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 10. Pinalitus viscicola (other names Orthops viscicola and Lygus viscicola). ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 11. Specimens of Anthocoris visci. Picture ©G H Green

Fig. 12. Ixapion variegatum, the Mistletoe Weevil. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 13 Ixapion variegatum, the Mistletoe Weevil. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 14. Ixapion variegatum, the Mistletoe Weevil. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 15. Six pictures of Ixapion variegatum emergence exit holes. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig.16. Ixapion variegatum larva extracted from Mistletoe stem below terminal bud. ©Jonathan Briggs

Fig. 17. Honey bee visiting Mistletoe male flower and acting as a pollinator of Mistletoe. ©Jonathan Briggs

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 30 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Great-crested Grebe nest sailing

John Clarke

I was down at Kemerton Lake Nature Reserve the other day during a gale when I noticed that a Great-crested Grebe’s nest floating across the lake, accompanied by the two adults. A branch supporting the nest (left of nest in pictures) had broken free and the whole thing had set off across the lake. It got about two thirds of the way across when the branch caught in some Potamogeton or other floating plant that stopped its progress. The nest was accompanied all the way by both birds – she tried several times to get onto the nest but it was no longer supported by the branch and partially sank so she had to get off. He swam around, sometimes alert, at other times preening or occasionally diving. It was a pathetic sight and I wished that I could have seen the outcome. They had less than 100m to go to reach the reeds where maybe they could have done some repairs. I guess that the outcome was disastrous but I will try to locate the nest at a later date. (written 26th May 2011).

Image

Fig. 1. Great-crested Grebe nest sailing before the wind with pair in attendance. Picture ©John Clarke

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 23 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Box Bug Gonocerus acuteangulatus in Edgbaston

Andrew Curran

On the 6th April 2011 the following email was received from Andrew Curran:

I decided to have a walk in the large wildlife garden near my home in Edgbaston, Birmingham, on a sunny morning. I came across what I thought to be my first Dock Bug of the year there. I took three pictures just in case. At home I had a look at the photographic guide (Evans & Edmondson) in the evening and suddenly realised that the bug did not seem right for Dock Bug. Then I looked at the various sites available on the internet. To my surprise theinsect looked more like Box Bug Gonocerus acuteangulatus (narrower abdomen at the rear, plain legs & antennal pattern). However, Box Bug should not be expected in the Midlands? I thought you might find my picture (taken on the 6th of April) particularly interesting and see whether the bug is actually a Box Bug or not.

Andrew’s picture was quickly emailed to several Worcestershire naturalists – the response was positive: Andrew had indeed found Box Bug!

John Meiklejohn commented: “The bug keys out clearly to Gonocerus acuteangulatus, Box Bug”.

Others remembered that Gary Farmer had mentioned Box Bug in a talk given at Worcestershire Entomology Day in 2009 as one to look out for as he had seen one in the Cotswolds and the species was known to be spreading. A picture accompanies his follow-up article in the Wyre Forest Review 2009 p56.

The British Bugs website states:

Historically the species was very rare (RBD1) and known only from Box Hill in Surrey, where it feeds on Box trees, this bug is expanding its range and now occurs widely in the south-east and beyond. It is also exploiting different foodplants, and has been found on hawthorn, buckthorn, yew and plum trees. See http://www.britishbugs.org.uk/heteroptera/Coreidae/gonocerus_acuteangulatus.html

This is a species worth looking out for. Superficially it resembles the common Dock Bug Coreus marginatus but is narrower and has sharply pointed extremities to the pronotum rather than bluntly angled.

References

British Bugs website at http://www.britishbugs.org.uk/heteroptera/Coreidae/gonocerus_acuteangulatus.htmlor search for www.britishbugs.org.uk and then for Box Bug in space provided.

Evans, M. & Edmondson, R. 2005. A photographic guide to the shieldbugs and squashbugs of the British Isles. WGUK.

Images

Fig. 1. Box Bug Gonocerus acuteangulatus. ©Andrew Curran

Fig. 2. For comparison a picture of Dock Bug Coreus marginatus. ©Harry Green

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 31 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

The identification of specimens and cataloguing of Worcester Museum Coleoptera (beetle) collection (update June 2011)

David M. Green

davidmxgreen@gmail.com

Begun summer 2010, the identification of specimens and listing of data of the Coleoptera (beetle) collection of Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum, Foregate Street, Worcester, continues. This work was described in the previous issue of Worcestershire Record (Green 2010).

Number of specimens identified so far: 5 781

Number of species identified so far: 1 130

According to museum documentation:

Number of specimens in collection: 11 460

Number of species in collection: 1 772

Therefore approximately:

50% of the specimens in the collection are now identified to species.

64% of the species are now identified to species.

Most of the specimens not yet examined are the weevils and the Staphylinidae on which I am presently working having covered the subfamilies Tachyporinae and Staphylininae. Some specimens have been noted on examination as requiring further work for identification; these I expect to return to when the whole collection has been examined.

Reference

Green, David M. 2010. Identification of specimens and cataloguing of the Coleoptera (beetle) collection of Worcester City Museum and Art Gallery. Worcestershire Record 29:9-10

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 31 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 31 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Dinoptera collaris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) specimens at Worcester Museum

David M. Green

davidmxgreen@gmail.com

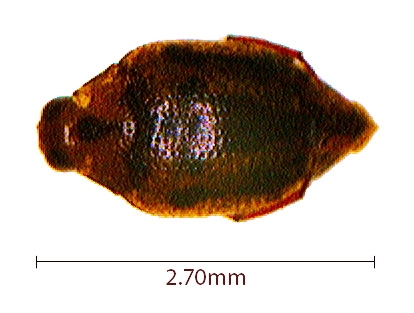

The longhorn beetle Dinoptera collaris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) is currently designated an Endangered species in the UK (JNCC 2011). Specimens of D. collaris are present in the Worcester Museum collection, originating from the collection of J. E. Fletcher of Worcester. The nine specimens were found by Fletcher close to Worcester, most recorded as “on flowers”, in June during the years 1881, 1885, 1883 and the last day of May 1886 – at Oldbury Farm, Temple Laugherne, Earl’s Court Farm and Whitehall. These sites are between the northwest of present day built-up Worcester and Broadheath, excepting “Whitehall” for which I have no unambiguous location. The photograph of one of the specimens from the Museum collection illustrates the distinctive appearance of the species.

According to Hyman and Parsons (1992), D. collaris (under the name Acmaeops) declined dramatically; it is associated with broad leaf woodland, chiefly oak, probably other broad leaf trees, especially on steep slopes on sandy soil. The larvae occur under loose dry bark of exposed rotten roots and pupate in the soil. Adults visit flowers, including blossom of trees.

The photograph also indicates the condition of typical specimens in the Museum collection. The V-cut in the specimen card mount is apparently to enable close-packing of the cards, such that the pin through the card in front fits into the V. This strange technique is quite often used in the collection. The cards are typically pinned into the drawer using a headless pin. All the specimens possess some surface dirt as can be seen in the picture, but seldom as to prevent satisfactory examination to identification.

References

JNCC 2011. Conservation Designations for UK Taxa. Taxon_designations_20110121.zip – http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-3408(10 June 2011)

Hyman, P.S and Parsons, M.S. 1992. A review of the scarce and threatened Coleoptera of Great Britain (1). U.K. Nature Conservation No. 3. JNCC.

Image

Fig. 1. The longhorn beetle Dinoptera collaris in the Worcester Museum collection. ©David M Green

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 51 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

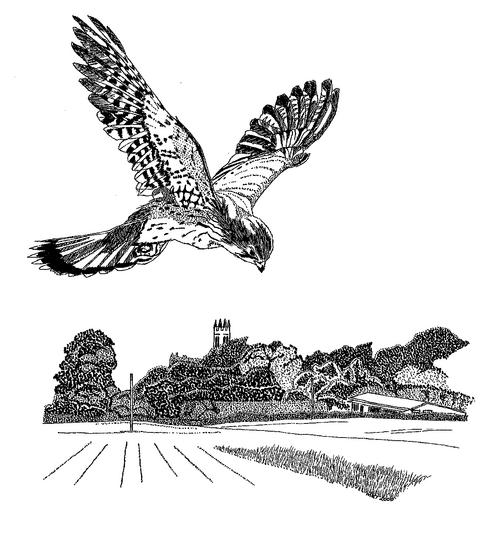

Buzzard stories

Harry Green (compiler); Martin Skirrow; Rob Harvard

Buzzard versus peregrine

Martin Skirrow

Yesterday (13th December 2010)), here at the farm near Berrow) at about 15.00hrs, I heard an agitated “kek-kek-kek-kek” and saw a female peregrine swooping repeatedly at something on the ground fractionally below my line of vision. After a couple of minutes to gain a suitable vantage point, I saw a buzzard fly up from the point of focus and make off with a carcase. The peregrine had given up a few moments before. On inspecting the site, there was a mass of scattered pigeon feathers and fresh blood. I assume the peregrine had made the kill only to have it stolen. In the nearby trees were many pigeons (flocks of 300+ have been around for several days) which, after the entertainment of seeing someone else eaten, departed. There was another fairly fresh pigeon kill site close by.

All this within 200 metres of my dwelling. Watching that peregrine with its swoops and Immelmann turns called to mind demonstrations at the Falconry Centre, except that instead of Jemima Parry-Jones with a lure there was a buteo with some booty!

Buzzards versus ducks

Rob Harvard

Cycling in this morning (12th April 2011) over the Severn bridge at the Ketch (S edge of Worcester) a Buzzard was hovering above the bridge and swooped down to attempt to take two ducks in flight as they were about to fly under the bridge. I’ve never seen anything like this since I saw a buzzard land on a pheasant when working in Wiltshire. I’ve noticed a pair of Buzzards often hovering above this bridge. Maybe they have found an easy way to hunt here?

Editors’s Note

Don’t underestimate buzzards – they ain’t a success story for nothing! Good addition to the Worcestershire Record series on what buzzards eat and do. The variety is endless. Please send in your stories

Image

Fig. 1. Buzzard Drawing by Ray Bishop

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 22 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Adomerus biguttatus ( = Sehirus biguttatus), the Cow-wheat Shieldbug re-found in Worcestershire

Harry Green (compiler)

On 30th March 2011 Nick Button found the shieldbug Sehirus biguttatus by the side of a ride in Worcestershire Wildlife Trust reserve Monkwood, near Sinton Green. The Worcestershire Biological Records Centre database contains two previous records from Monkwood dated August 1968–June 1970. Of these, one grid reference is for the centre of the wood, the other at the north end. The records are by I L Crombie and the time span suggests he found them in the wood on several occasions. Apparently Monkwood has been the only known location in Worcestershire for many years: there are also records from the Shropshire part (north side) of Wyre Forest.

The British bugs website states: A medium-sized shiny black shieldbug which has a pale margin to the pronotum and forewings and two pale spots on the corium. This species can be found under stands of the foodplant, Cow-wheat Melampyrum pratense, growing in sunny woodland clearings and rides. There is one generation per year, the new generation becoming adult in August. Scarce, with a scattered distribution mainly confined to southern England and south Wales. It has declined in recent years due to the widespread neglect of traditional woodland management practices which create suitable cleared areas.

Evans & Edmondson (2005) note that it is a ground living species found in the sunnier parts of woodlands on various soils. In Worcestershire the associated food plant, Cow-wheat, tends to have a more westerly distribution. This being so, and encouraged by Nick’s record, the Wyre Forest Study Group searched hard for the bug and found it on 16th April 2011 near Uncllys in Wyre Forest. Rosemary Winnall writes as follows:

On a recent field trip, the Wyre Forest Study Group was delighted to find a small insect that some members had been searching for for a while! Paul Allen (ably encouraged by Brett Westwood) eventually spotted the tiny 5.5mm long shieldbug Sehirus (Adomerus) biguttatus on a sunny bank in leaf litter under its food-plant Common Cow-wheat Melampyrum pratense. In previous searches we had been looking on the plants, but Paul instead heaped some leaf litter from below the Cow-wheat into a white tray and searched through carefully. No others were found in spite of checks on the food-plants – perhaps it comes out to feed at night? The shieldbug was fast moving and was not keen to be photographed!

It seems likely that this species will occur at other sites in Worcestershire where there is Cow-wheat. It is however hard to find. The early stages are probably present during June and July. The full-grown insect may be found from August through to the following spring. Since Monkwood became a nature reserve there has been a programme of re-instating coppice regimes and widening the main ride. Both these practices have created open sunny areas favoured by the bug so hopefully the population will grow. Nationally the species appears to be uncommon with widely scattered records shown on the map derived from the NBN website but this may perhaps reflect its elusiveness rather than great rarity.

References

British Bugs website at http://www.britishbugs.org.uk/heteroptera/Cydnidae/adomerus_biguttatus.htmlor search for www.britishbugs.org.uk and then for Adomerus biguttatus in space provided.

Evans, M. & Edmondson, R. 2005. A photographic guide to the shieldbugs and squashbugs of the British Isles. WGUK.

Images

Fig. 1. Adomerus biguttatus (Sehirus biguttatus), Monkwood, March 2011. ©Nick Button

Fig. 2. Adomerus biguttatus (Sehirus biguttatus), Wyre Forest, April 2011. ©Rosemary Winnall

Fig. 3. Adomerus biguttatus (Sehirus biguttatus), Wyre Forest, April 2011. ©Rosemary Winnall

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 33-34 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Hornet stories: Hornets stripping bark and also catching fly; Hornet nest in cordwood near Tiddesley wood and in old nest box

Harry Green

(compiler)

In recent years the rapid spread of hornets throughout most for Worcestershire from western strongholds has given rise to a number of stories reported in previous issues of Worcestershire Record. Here are a couple more. The editor is always interested to receive more!

Hornets stripping bark and also catching fly

This picture (Fig. 1) was sent to Caroline Corsie at Worcestershire Wildlife Trust by Douglas Gregor. He wrote: in case it is of interest I attach a photograph of a couple of hornets stripping bark from an ash sapling in Monkwood at the end of October. Flies were beginning to irritate them and in this picture one of the hornets did take its vengeance! The question is, why were they stripping living bark? Perhaps to obtain sap which, once flowing, would probably attract flies. Many insects, including wasps and hornets, are attracted to sap runs on trees, especially as they develop the late-season sweet-tooth.

Hornet nest in cordwood near Tiddesley wood and in old nest box

Harry Green

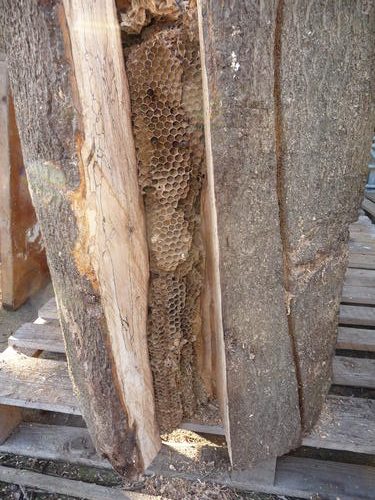

Volunteers working at the old barns near Tiddesley Wood, Pershore, were fascinated watching many hornets flying in and out of a small hole is a large (about 2 metres long) piece of beech destined for firewood logs. When the time came for logging-up the contactor carefully cut open the log with a chain saw to reveal the carton nest build along a narrow tunnel over one metre long, here illustrated (Fig.2, Fig. 3 & Fig. 4). Irregularly constructed hornet nests are commonplace iin tree cavities while those hanging free in roof-spaces or the like are usually more or less globular in construction.

Hornets often take over nest boxes put up for birds. These are usually too small for purpose and hornet nest construction flows round the outside of the box. In 2010 hornets occupied an old nest box in Tiddesley Wood. The box is a bit larger than the usual tit box and was becoming rotten as the hornets chewed through the bottom and probably used the paper manufactured from that source to help construct their nest (Fig. 5, Fig. 6 & Fig. 7)

Images

Fig. 1. Hornets stripping bark on ash sapling and catching fly. Picture ©Douglas Gregor.

Fig. 2. Entrance to hornet’s nest in beech cordwood. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig. 3. Hornet nest about one metre long in rotting beech log cavity. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig. 4. Hornet nest about one metre long in rotting beech log cavity. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig. 5. Hornet nest in nest-box. Those parts of the nest exposed to the weather on the outside of the box have disintegrated. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig. 6. Hornet nest in nest-box. The hornets have chewed through the base of the box. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig. 7. Hornet nest in nest-box. The hornets have chewed through the base of the box. Picture ©Harry Green.

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 32 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

New species [in Africa] for a Worcestershire recorder [Will Watson]

Harry Green

For the naturalists of Worcestershire Will Watson is a familiar face. He is a freshwater ecologist who used to live in Worcester and now lives near Bromyard. He often contributes records to the Worcestershire Biological Records Centre and adds an aquatic dimension to our special recording days. He has recently received an unexpected honour, probably unique in the annals of our local naturalists. In January 2011 we were delighted to receive the following email (Ed).

An email from Will: “Great news. I am able to confirm that I did discover a new species of water beetle on the Manda Wilderness Reserve in Mozambique. The beetle was found during both of my trips in 2008 and 2009. It has been named Haliplus watsoni which is a little bit embarrassing but a great honour. It has all been written up in a Dutch scientific paper Netherlande Entologische Vereniging: http://www.nev.nl/tve/html African Haliplidae (Coleoptera) by Bernhard J. Van Vondel. Volume 153 239-314 December 2010.

PRESS RELEASE:

Herefordshire man discovers new species

Over the course of two scientific expeditions to the subtropical rainforests of Mozambique, Will Watson, Wildlife Consultant from Docklow discovered a species of water beetle new to science. The 2.7 mm long diving beetle has been named Haliplus watsoni. Will says:

“I am absolutely chuffed to have found a new species of beetle and honoured to have it named after me. This is a particularly rare accolade as it is not normal convention to name species after the finder. The expedition had its moments of risk. I was initially concerned by that I might be confronted by crocodiles and hippos. However, in the end I was infected by the microscopic parasite which causes bilharzia. But this makes all the pain and effort worthwhile”

The water beetle was discovered in 2008 in a floodplain pool on the Manda Wilderness Community Game Reserve which is managed in association with the local community by Nkwichi Lodge. The reserve is in northern Mozambique in the Great Rift Valley and borders Lake Niassa (also known as Lake Malawi) which is 365 miles long and 55 miles wide and is the 9thlargest lake in the world. Further water beetle specimens were collected on a second trip to Mozambique in 2009. The reserve covers 130 000 hectares; just over half the size of Herefordshire but with a fraction of its population. It is an unspoilt wilderness with Brachystegia forest, savannah, swamps, streams, mountains and miles of sandy beaches with crystal clear water.

It took a year and half for the beetle’s identity to be confirmed by international water beetle expert Bernhard Van Vondel and others in the scientific community. Its discovery comes at a time when the Mozambique Government and the World Wildlife Fund are in the process of establishing the Lake Niassa Reserve and the Manda Wilderness Community are developing eco-tourism on their reserve. This find indicates how valuable the surrounding freshwater habitats are for biodiversity and should help inform and direct conservation efforts.

Images

Fig. 1. Haliplus watsoni. Picture ©Will Watson

Fig. 2. The floodplain pool in northern Mozambique where the beetle was found. Picture©Will Watson

Fig. 3. Nile Crocodile photographed on Lake Niassa in 2008. Picture ©Will Watson

Fig. 4. Will with his pond net in a lakeside pool. Picture ©Will Watson

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 38 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Bechstein’s Bat – the national survey comes to Worcestershire

James Hitchcock

The Bechstein’s Bat Myotis Bechsteinii project is part of the National Bat Monitoring Programme which began in 2007. The project aims to survey woodlands in Southern England and South Wales over a four year period using a new trapping technique. The project works with local bat groups to help with the surveys. Gathering useful information on the bat’s range and its habitat preferences are a key objective of the survey.

Bechstein’s Bat is one of the rarest mammals in the UK, and a UK Biodiversity Action Plan priority species (Bat Conservation Trust). It has proven difficult to detect in previous attempted surveys as it rarely leaves the canopy of its favoured broadleaf woodland habitat. The current survey is the first time that anyone has attempted to map its distribution and to obtain information to inform woodland management.

Frank Greenaway and David Hill, who are leading Bat researchers, have developed and tested a technique to relay ultrasonic social calls to locate Bechstein’s Bats. The project is relying on the involvement of experienced, specially trained volunteers recruited through the local bat group network, and the support of landowners and woodland managers.

The plan is to survey four or five counties or areas during each year of the project. The 2009 survey focused on Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Kent, Oxfordshire and Surrey.

In 2010 the project came to Worcestershire – along with Gloucestershire, North Buckinghamshire and Somerset – with the local Worcestershire bat group surveying 15 woodlands around the county, catching 101 bats of nine different species. In total six Bechstein’s were caught at three different sites (Records from Jane Sedgley; Worcestershire Bat Group) in the county, one of which, Grafton Wood, is owned and managed by Worcestershire Wildlife Trust (WWT) and Butterfly Conservation (BC). Another site is Romers Wood, owned and managed by Herefordshire Nature Trust. The third site is not being named as it is in private ownership and has no public access.

In Britain the last population estimate for Bechstein’s Bat in 1995 put the pre-breeding number at just 1500 (Bat Conservation Trust). The UK is currently on the northerly edge of the known breeding range. Bechstein’s are most often associated with broadleaved woodland, needing at least 25 hectares to support a nursery colony. Mature trees between 80-120 years of age are required along with a good supply of old woodpecker holes where the bats set up their roosts. They feed by hawking and gleaning. Its low population density combined with an exacting set of habitat requirements make it particularly vulnerable to habitat loss.

The records gathered from this work are currently the most northerly that are known for the species. Because of this further survey work is being planned by WWT and BC to try and identify which areas of Grafton Wood are being used by the bats. We also hope to try and identify other woodlands in the surrounding area that are inhabited and ascertain if they are important in supporting the local population. The national survey only allowed one woodland per 10km square to be visited so there is certainly scope for visiting woodlands around Grafton Wood, such as Trench Wood. The work will hopefully be done as part of the national project through the Worcestershire bat group but it is likely that any radio tracking to identify roosts will be carried out by paid consultants funded by the Trust. We are delighted to find the Bechstein’s in our woodland and are currently working through the management guidance literature to ensure that we take account of the habitat requirements of this species during forestry work.

Images

Fig. 1. Bechstein’s bat. Picture © Derek Smith.

Fig. 2. Grafton Wood showing habitat favoured by Bechstein’s Bat. Picture ©James Hitchcock.

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 40 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Harsh winter for wrens

Garth Lowe

The winter at the end of 2010 was a particularly harsh one, starting very early with the first snow on the 26th Nov and the cold spell continuing through most of December. On nine days in this period the maximum temperature at Old Storridge never got above 0°C with some night temperatures dropping to -10°C.

These conditions put a great strain on the resident birds especially those with the least body mass such as the wren. A timely reminder from a resident of Birchwood Lane, just a ten minute walk through the woods, encouraged us to see a phenomena not observed very often. During the last winter he had observed a number of wrens going to roost in a bird box attached to one corner upright of an open barn used as a workshop, and claimed there were at least twenty entering the box. On the evening of the 19th December 2010 with the daily maximum having only reached -3°C that day, I met my sister Cherry Greenway and her husband to see how this activity actually worked.

In snowy conditions I arrived at the box at around 3 40pm with no birds to be seen and I thought it was too late and they all must be in the box as it was so cold. By 3 55 three pairs of eyes were studying the box when the first wren arrived, hung about for a bit and then went in only to reappear again as if to say I am not going to be the first! This was repeated a few times by more wrens, which had started to arrive. By 4 10pm just a few had stayed inside, but others kept on arriving and continuing with the in and out action.

By nature this bird cannot be called a social bird, setting up territories in the spring and defending them against other male wrens, so this winter gathering has to overcome that part of their make up. It is an ingenious scheme, all huddling together in a sheltered area through long cold nights, so saving on the loss of body heat. The speculation is how did this evolve?

The numbers going into the box continued to be monitored with the figure rising steadily, but dropping back still as a few birds kept coming out. The figure of 20 was soon passed and then 30, which we thought quite unbelievable in one normal sized bird box. A figure of 40 was then reached, with more wrens still arriving by the minute and queuing up around the site, so it was speculated we might even reach 50! At 4 30pm things went very quiet so the observation was terminated. It is true to say that 50 wrens were seen to go in but two came out at the end and went elsewhere, leaving still an incredible figure of 48 all tucked up warmly inside.

It is also a remarkable fact that there were still so many wrens still alive in the surrounding district with the inclement conditions. Since this number could not all be living closely around the site, some birds must have flown in quite a distance from their territory to the box. The last question of course is just how all these birds get to know that there is a wren Hilton, where they all gather for the night? Memory must work quite well as it was used last year, but how did all those youngsters from this year cotton on to this fact?

It was a magical 45 minutes watching the wrens performing their going to bed actions, which must have taken place night after night in the long period of intense cold.

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 40 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 23-24 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Striking red and black bugs (Hemiptera – Heteroptera) in Worcestershire

John Meiklejohn

(There is an increasing number of sightings of striking red and black bugs in Worcestershire. Hopefully this article will encourage readers to look out for them and send in records. Ed.)

Eurydema ornata (Fig. 1.)

In March 2000 I was given a striking red and black coloured shield bug that had emerged from purchased broccoli in a house in Westmancote, on the southern slope of Bredon Hill. Using P.Kirby’s Draft Key for British Heteroptera, it was identified as Eurydema ornata. The British Bugs website states: a relatively recent arrival in the UK, but now established in the Channel Isles, and in Dorset and Hampshire; it may also appear at other places in south England. It spends the winter as an adult and feeds on crucifers, including cress, radish and cabbages.

Eurydema dominulus is very similar to and slightly smaller than E. ornata. It lacks the dark spot on the embolium of the wing. There are a few U.K. records for this species, mainly from Kent and Sussex. The British Bugs website states: a very scarce species found in woodland rides in parts of southern England. Most records are from Kent and Sussex.

Eurydema oleracea (Fig.2.)

In June 2005, whilst with a party from the South-east Worcestershire local group of the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust in the Umbria region of Italy, I collected another brightly coloured, red and black shield bug. This was determined as Eurydema oleracea, the Brassica Bug, a bug associated with cruciferous plants, particularly with Horse-radish, Armorica rusticana. The form with the red markings is less common than the form with white markings. There are records in Worcestershire Biological Records Centre for this bug from John Partridge, 2004, and Kevin McGee (2007). Kevin published the picture (Fig. 2) and wrote as follows: The Brassica Bug. My first UK records for this mainly southern species were both from Oilseed Rape flowers near Deerfold Wood, Drakes Broughton on 5.5.2007 & 20.5.2007.

The British Bugs website states: well distributed in southern and central England; may be locally frequent and appears to be increasing in abundance.

Corizus hyoscyami (Fig. 3).

Another similarly coloured bug which is becoming more common than the above species is the rhopalid bug Corizus hyoscyami. It has spread from the south-west of England where it was first recorded and was first found in Worcestershire in the Redditch area in 2006 by Gary Farmer. It is a polyphagus species and known to feed on Storksbills. There are five Worcestershire records for it in Worcestershire Biological Records Centre. The British Bugs website states: locally distributed in sandy habitats around the coasts of southern Britain, this species has recently been found more frequently inland. It is associated with a range of plants, and overwinters as an adult, the new generation appearing in August-September. Nymphs are yellow/red-brown in colour and also rather hairy.

McGee (2007) also wrote as follows: Corizus hyoscyami (Rhopalidae, local). One of these striking red & black bugs was found on ground vegetation in the garden of ‘The Newalls’ at the Wyre Forest by John Partridge at the end of a Wyre Forest Study Group field trip on 21.4.2007. Just as I was about to take a photo it took flight and was not relocated! Please also see page 41 of the November 2006 issue of the Worcestershire Record for previous reports of this species which is yet another spreading up from the south.

Pyrrhocoris apterus

A red and black bug that has to date only been regularly recorded from a rock off the coast of South Devon but is common in Europe is the Red Fire Bug, Pyrrhocoris apterus. It can easily be confused with Corizus hyosciami but as it is associated with Tree Mallow it is unlikely to turn up in Worcestershire.

References

The British Bugs web site is a useful source of information and pictures: http://www.britishbugs.org.uk.

Evans, M & Edmondson, R. 2005. A photographic guide to the Shieldbugs and Squashbugs of the British Isles. Published by WGUK in association with WildGuideUK.com.

McGee, K 2007. Records of Note 2007. Worcestershire Record 23:42-46.

Images

Fig.1. John Meiklejohn’s specimen of Eurydema ornata. Picture ©Harry Green.

Fig.2. Eurydema oleracea. The white and black form with red marks replaced by white. Picture ©Kevin McGee.

Fig.3. Corizus hyoscyami at Grafton Wood 3rd January 2011. Picture ©Tony Simpson.

Worcestershire Record | 30 (April 2011) (ISSN 1 475-9616) page: 25 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

The Terrapins of Worcestershire County Hall

Wade Muggleton

For many years at Worcestershire County Hall there has been a story of Terrapins living in the ornamental lakes in front of the building. When I started working here it seemed a bit of a farfetched story, but it is true enough and here is a photo I took of them. They have been living here now for well over a decade, there are at least three, possibly more; one colleague claims to have seen six at once, and they obviously find enough food to prosper in what is a shallow man-made lake with little decent habitat or marginal vegetation. In the summer they can often be seen basking out on the brick work, and seem quite acclimatised to the comings and goings of people.