Issue 37 November 2014

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 23-24 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Dragonflies in Worcestershire 2014

Mike Averill

Following the previous year’s prolonged cold spring right in to May, the weather in 2014 was more like a normal year with gradually increasing temperatures through April and May. Through the year 24 species were seen out of the 28 so far recorded in the county. Nearly all species emerged earlier than last year and a few were actually earlier than in the 2008-12 period, namely the Common Club-tail Gomphus vulgatissimus and Scarce Chaser Libellula fulva. It’s worth noting that 13 of our Dragonflies and three of our Damselflies emerge early in spring as a synchronised event. These are usually species that have at least a two year cycle but delay emergence through the previous Autumn and wait until the following year to enable them to emerge early in the next April/May. All the early synchronised species are very susceptible to poor weather and can easily vary their first dates by as much as three weeks.

As the year progressed in to 2014, the weather was occasionally fine and memories of the summer are likely to be good with long spells of fine weather (16 dry days in June, 23 in July, 11 in August and 23 in September), yet as a year it was very wet and September was the only month with below average rainfall. This continuation of regular rain was ideal for dragonflies, wet enough to keep pools full yet with long dry sunny spells allowing the adults to fly regularly. This is good weather for aquatic insects but perhaps not so good for butterflies and bees.

Recording transects are a really useful way to get a meaningful trend in dragonfly numbers through the year, which can in turn be compared to other years. Taking counts over a measured distance and repeating the visit each month in good weather can give a better idea of numbers where subjective impressions cannot. In the case of the counts on the River Avon at Eckington, most species had an upturn in numbers compared to last year, the only exception being the Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma najas. This upturn followed a two year decline in 2012 and 2013 for the White-legged Platycnemis pennipes, Blue-tailed Ischnura elegans and Common Blue Enallagma cyathigerum damselflies (01). Species with too small a count to see on the graph like Scarce Chaser, Common Darter Sympetrum striolatumand Large Red Damselfly Pyrrhosoma nymphula also had a slight upturn. Another species that has recovered a little in 2014 after a large decline from 2009 is the Banded Demoiselle Calopteryx splendens. It is not clear why 2009 was such a good year for this species but it did have a very warm Spring followed by long hot spells in the summer. Whatever the reason, the species has not done nearly as well since.

In Croome Park all species were also up this year, recovering from a poor 2013. The Small Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma viridulum did very well indeed this year exceeding all previous years counts. Elsewhere the Small Red-eyed popped up in various places including Lower Smite Farm, Hanley Swan, Purshull Green Pool, Hartlebury Riverside Pool, several pools at Grimley, Pirton Pool, a few river locations on the Avon near Pershore and one farm pond near Berrow in the very south of the county. This is significant because although this species has been with us since 2006, having arrived in the UK in 1998, it has not really consolidated its position elsewhere before this and it was thought that the westerly spread had slowed up to a halt.

Other dragonflies that are doing well are the Four-spotted Chaser Libellula quadrimaculata and the Beautiful Demoiselle Calopteryx virgo. The Four-spotted chaser seemed to appear in all sorts of locations this year whereas it was confined to just a couple of sites 20 years ago. The Beautiful Demoiselle is another species that has changed its distribution where, 20 years ago it stuck to the westerly tributaries of the Severn it can now be found in small streams throughout Worcestershire and even on the river Cole in the old Vice County area of Birmingham (A separate account from Des Jennings will appear in volume 38 April 2015 issue of Worcestershire Record).

The Scarce Chaser Libellula fulva was quite prominent on its stronghold along the Avon and has in fact spread up to the Warwickshire border this year. It was seen on Hillditch Pool again where it breeds in low numbers and also once again at Hurcott Pool where a mated male was seen.

Another species, also found on our rivers at the same time, the Common Club-tail Gomphus vulgatissimus had another good year at Bewdley where emergence numbers were the third highest in seven years. On the Avon though, there are signs that it is struggling as fewer individuals were seen above Pershore and apparently none were seen in Warwickshire for the second year running. It is hard to know why this is happening as the Scarce Chaser which has a similar life cycle and habitat requirements is doing quite well and so does not suggest there is a water quality issue.

Our regular visitor the Red-veined Darter Sympetrum fonscolombii made an early appearance(23/6) at Pirton Pool but wasn’t seen anywhere else this year.

Normally only seen in the Wyre Forest area, the Golden Ringed dragonfly Cordulegaster boltonii was seen by chance at the Devils Spittleful egg laying in a leakage by a water trough. There is no mistaking this species, when seen ovipositing, as the female prods her abdomen in soft silt like a garden dibber to insert her eggs. This species is normally found on rivulets and seepages, so it was a surprise to find two shed larval cases, this year, along the Severn at Bewdley but this location was just downstream of Dowles Brook so perhaps they had been washed out of there in the January floods.

A late species to emerge, the Migrant Hawker Aeshna mixta, was very evident in September due to the fine weather and it gave the opportunity to watch where they laid their eggs at Hartlebury Common. They choose the Soft Rush Juncus effusus and lay about 10 cms above the water line in to the older browner stems. They may well try other woody vegetation but reject anything hard like brambles and tree species preferring rush where the eggs can be inserted in to the stems to lie in the soft tissue inside(02). Each egg is about 1.7mm long shaped like a long cylinder with an opening called a micropyle at one end. This opening firstly allows sperm to enter the egg for fertilisation and later it is the place where the prolarvae emerges. The egg is laid at an angle downwards in to the plant so that the micropyle is nearest to the exit hole. The recess in the plant tissue is made by a knife like device called the ovipositor which cuts a hole and also carefully inserts the egg in to the slot. The way that the dragonfly exerts enough pressure to punch a hole in to the plant is by forming an arch over the stem between the legs and the end of the abdomen and by flexing the middle abdomen the ovipositor is forced in to the stem (03). Each egg is laid separately within its own hole, the next one being laid about 0.5 cm away so that on average there are 25 eggs per 10 cm. These eggs will remain safe and secure in the stems until the spring when they emerge as prolarvae and drop in to the water below. All hawker dragonflies and all damselflies lay eggs in to plant material like this while the darters, skimmers and chasers lay their cluster of eggs on to plants or directly in to water.

An uncommon Worcestershire dragonfly, the Common Hawker Aeshna juncea was seen twice this year, once at Penny Hill egg laying and once at Hartlebury Common.

The mention of Hartlebury Common twice in an article about dragonflies is a real treat as it is a site that has deteriorated badly over the last 50 years due to drying out of water features. This year was without doubt the best year for dragonflies in recent memory with 18 species recorded there. The key to this was the fact that we have had three wet years in a row leading to permanent standing water in the Rush Pool and the Bog which has enabled species with two and three year cycles to succeed in breeding there. It is a lowland heath site and is the only place in Worcestershire where we can see the classic heathland species like Common Hawker, Emerald Damselfly Lestes sponsa and Four-spotted Chaser together. The only one missing is Black Darter Sympetrum danae so perhaps that one will appear next year as it has been seen at Hartlebury in the past. Other than these heathland species, the fact that 18 species were present through the year made the site quite a spectacle and provides an opportunity to really compare similar species like Scarce Chaser, Broad bodied Chaser Libellula depressa and Four-spotted Chaser.

While the wet weather has helped the situation on Hartlebury Common the chances are that we will return to drier conditions in the coming years and so it is important that the Council and Natural England press ahead with plans to support the water levels on the site during dry spells using a groundwater pump. This will not only benefit dragonflies but all the other aquatic invertebrates and plants that make the site special.

| 01. Eckington dragonfly transect 2009-14. |

| 02. Migrant Hawker egg in plant stem. Mike Averill. |

| 03. Migrant Hawker inserting egg into Juncus effusus stem. Mike Averill |

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 23-24 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 4 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Identification of Scorpion Flies

Mike Averill

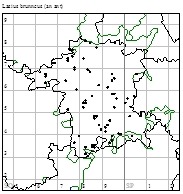

Following Martin Mathews excellent Gloucester Mecopterans numbers 1 & 2 reprinted in the Worcestershire Record No 36 there is at last a reliable way to identify the three different species likely to be encountered in Worcestershire. Following recording in 2014 this note confirms that it is easy to identify the males without the need for dissection. All that is needed is an examination of a male or of a good photograph of the underside of the male genital capsule. Thankfully the male usually holds this uppermost giving the group its familiar name. When held like this there are two structures called hypovalves on the surface which are characteristic of the species (see guide 01).

Both Panorpa germanica and P. communis are reasonably common, but P. panorpa is less likely to be found.

Although it is recommended that the genital capsule is the positive way to split the species, the markings do seem different within the three species seen. Panorpa communis usually has the darker black markings with very little additional spotting. P. communis and P. germanica are superficially more similar with paler black markings and more of them. There is fourth species P. vulgaris which may well arrive in the UK and it is similar to P communis but with more dark black spots so watch out for that.

It is hoped that this note will aid the further identification of Scorpionflies in the county.

Reference

Matthews, M. 2014. The Gloucester Mecopteran. Worcestershire Record 36:24-27

01. Guide to identification of scorpion flies. Mike Averill

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 4 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 10-11 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Lasius brunneus (Latreille, 1798). The Tree Ant, Nationally Notable (Na) at Hurcott, Kidderminster

John Bingham & Denise Bingham

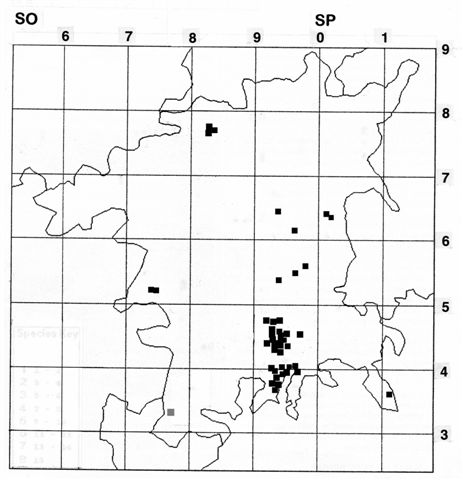

In the Worcestershire Record Harry Green (1998) provided a note on the distribution of Lasius brunneus in Worcestershire drawing attention to a paper by Alexander and Taylor (1998) on the Severn Valley as a stronghold for the species. The Thames Valley was the main stronghold for the species until the 1960s when it was reported from the Severn Vale in Gloucestershire and south Worcestershire. Shropshire had one record from Dudmaston Park in 1996. Parkland sites such as Croome Park and Hanbury Park appear to be the typical habitat in Worcestershire. Harry considered that it seemed likely that the species has been under-recorded rather than showing a recent extension of range. More records are now known but the ant is probably still under- recorded.

On 21st April 2014 Denise and I were recording our local patch at Hurcott, Kidderminster when Denise swept up a number of ants from a patch of flowering White Deadnettle Lamium album at grid reference SO848776. I identified the ants as Lasius brunneus but to confirm this I sent an image to Harry and Geoff Trevis, who both who agreed (01). The area around Hurcott has a number of large oak trees in the fields and hedgerows and the land is managed as low intensity horse pasture. Whilst not parkland it has some similarities, so it is perhaps not that surprising that L. brunneus was found here. Why it was swept off L. album is not clear, perhaps an early nectar source or were tiny aphids present on the plant? Searching the large oak trees nearby a few days later failed to reveal any ants, but they do remain well hidden in crevices so perhaps this was to be expected. The hedgerow had many old dead and dying bushes and old wooden fence rails, all possible habitat for ants. I did eventually find the ant in low numbers on a sycamore tree about 0.4 km away to the north at SO847779.

As worker ants are fugitive and rarely seen on the host tree surface perhaps sweeping any flowering plants of L. album in early spring might be a way of providing records of this elusive ant, especially if large oak trees are present nearby. As yet we have yet to see the ant on the nearest old oak to the Hurcott L. album site, but the tree has deep crevices!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Harry and Geoff for the identification.

References

Green, H. 1998. The brown ant: Lasius brunneus (Latreille). Worcestershire Record 4:12.

Alexander KNA & Taylor A. 1998. The Severn Vale, a national stronghold for Lasius brunneus (Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). British Journal for Entomology & Natural History 10:217-219.

Editors note.

Since 1998 Lasius brunneus has been found in many places across Worcestershire almost always on tree trunks in parkland, orchards and elsewhere. Special studies of old orchards for other species have almost always detected Lasius brunneus. I (Harry Green) have swept it off flowering Ramsons Alium ursinum on two occasions in May, once on hawthorn flowers Crataegus monogyna in May and also amongst leaf litter beneath trees on one occasion. These visits to plants other than trees are rarely reported and not understood.

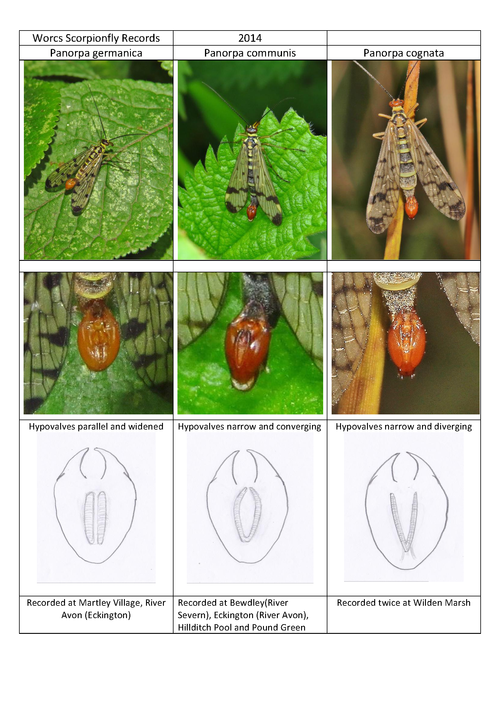

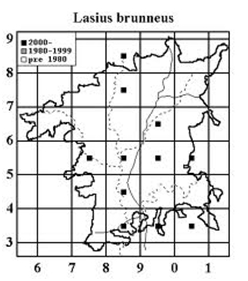

Geoff Trevis is producing a Worcestershire Atlas of Aculeate Hymenoptera which should be printed in 2015. His comments together with a distribution map (02) on Lasius brunneus appear below: compare with the map from the 1998 paper (03).

Lasius brunneus (Latreille, 1798).

Formicidae: Formicinae

Has a curious distribution with two separate populations, one based around the Thames valley and extending north into East Anglia and south into the North Downs and the other in the Severn Valley up to Shropshire. In these areas it is common and not threatened.

Habitat: Generally nests in mature, living trees but has been found in stumps, hedgerows and timber framed buildings.

Flight Period: Queens and males fly in June or early July.

Worcestershire Records: The species is widely distributed across the county with 92 widely distributed records. Nationally this remains a rare species.

01. Lasius brunneus at Hurcott. John Bingham.

02. Lasius brunneus distribution map 2014

03. Lasius brunneus distribution map 1998

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 10-11 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 11-12 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Mordellistena (Mordellistena) variegata (Fabricius, 1798) (Coleoptera, Mordellidae) at Kidderminster

John Bingham & Denise Bingham

On 24 July 2014 Denise beat a small beetle from a Rowan tree in our garden (01, 02). It was quite well marked and colourful but belonged to a group of tumbling flower beetles Mordellistena, not easy to identify and with some quite rare species. Help was at hand and thanks to Paul Whitehead who identified the beetle from an image sent to him as Mordellistena (Mordellistena) variegata and provided information on distribution. In the note that follows he reports more fully on identifying species in this small group of interesting beetles.

The beetle is widespread but localised in the English midland region extending from lowland river floodplain level to at least 160 m a.s.l. on Bredon Hill, Worcestershire. Host trees include Pedunculate Oak Quercus robur L., Field Maple Acer campestre L. and now Rowan Sorbus aucuparia L. This last is perhaps unsurprising given that M. variegata is a well-known inhabitant of traditional pome fruit orchards in the region.

The Mordellidae or ‘tumbling flower beetles’.

Paul Whitehead

The Mordellidae or ‘tumbling flower beetles’ has always challenged human comprehension. The late Mr A. A. Allen, one of the greatest of the recent British coleopterists described new species of Mordellistena in both 1995 and 1999 neither of which have stood up to subsequent scrutiny. The group is generally well known for the apical abdominal segment being extended to form a so-called pygidium (Gr. pygidion = rump). This is especially conspicuous in the black Mordellistena which are especially speciose in southern Europe and which mostly breed in the rigid stems and rootstocks of Asteraceae, including Artemisia spp. and occasionally those of other groups such as Campanulaceae (e.g. Jasione).

Only three of the 12 British species of Mordellistena are not black viz. the scarce widespread M. neuwaldeggiana (Panzer, 1796) which is more or less uniformly brownish-orange and thus immediately recognisable; M. humeralis (L., 1758) which is variegated black and dull yellow-orange rarely with the pronotum darkened and M. variegata (F., 1798) which (in numerous examples seen) has clear orange vittae running obliquely away from the elytral humeri and the pronotum usually darkened but paler laterally and with the antennae longer. These three species are arboreal as larvae in a wide range of deciduous trees usually in soft delignified wood; M. neuwaldeggiana occurs in traditional orchards. In the English midlands I have numerous records of these species with the exception of M. humeralis which I have not yet seen in Britain. Male M. variegata have diagnostic subcircular last palpal segments whereas these are not dilated in male M. humeralis which also has relatively shorter antennae.

Other genera likely to be encountered in the region are Mordellochroa and Variimorda. Female Mordellochroa abdominalis (F., 1775) are unique and unmistakeable in the British fauna being black with clear red pronota; the males have darker pronota and may be confused with species of Mordellistena and Mordella. Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) is a known larval host in Worcestershire. Variimorda villosa (Schrank, 1781) is the only British representative of the genus and may be recognised by the pattern of shimmering bronze hairs forming transverse fasciae on the black elytra. Both of these robust species are arboreal as larvae although V. villosa has a demonstrable preference for Salicaceae in riparian situations. Mordella, a genus of mostly robust black species includes two British species which are either rare or localised; M. holomelaena Apfelbeck, 1914 may occur in the region but I am not aware of modern records.

For anyone wishing to acquaint themselves with the finer details of this group I would recommend perusal of Batten, R., 1986. A review of the British Mordellidae (Coleoptera). Entomologist’s Gazette 37:225-235. They might also consider forming a collection taking no more than a minimal number of specimens. As ‘tumbling flower beetles’ mordellids prefer to visit flowers with exposed nectaries, notably those in Rosaceae and Apiaceae and with records also from flowers of Sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus L. Finally (with a few clear exceptions) do not rely on the internet to inform decisions; many such images are based on misidentifications.

01. Mordellistena variegata at Kidderminster. John Bingham.

02. Mordellistena variegata at Kidderminster. John Bingham.

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 11-12 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 12-14 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Coleoptera of note in the Kidderminster area 2014

Alan Brown

I spent the season occasionally visiting a couple of my local haunts, Springfield Park (SO87) and Devil’s Spittleful Nature Reserve (SO87), but my main focus concentrated on a 400 metre stretch of River Severn bankside (SO77) that runs alongside Bewdley town centre, downstream towards Stourport. All observations were made at night with a headband torch.

01. Aegialia sabuleti Scarabaeidae (Nationally scarce) 3/5/2014

A riparian species of scarab beetle found on bare river sandbanks on rivers and streams where it feeds on decaying vegetable matter. This species is very local in the south with most records coming from northern England. Found active at night alongside the river in Bewdley.

02. Dorytomus tremulae Curculionidae (Nationally scarce) 22/4/2014

A species of catkin weevil restricted to feeding on Aspen trees, the adults feed on leaves but the larvae develop in the catkins. I found this one active at night on a mature Aspen trunk at Springfield Park, Kidderminster. Also seen on Aspen alongside the River Severn at Bewdley.

03. Dorytomus tortrix Curculionidae (Local) 23/4/2014

Another species of catkin weevil linked to Aspen, I found these in large numbers on Aspen trees in Kidderminster and along the River Severn in Bewdley on 3/5/2014.

04. Xyleborus saxesenii Scolytidae (Local) 3/5/2014

A rather local bark beetle in Worcestershire, I found a number of these on decaying bark on a dead plum tree alongside the river Severn, Bewdley, active at night.

05. Stereocorynes truncorum Curculionidae (Nationally rare) 22/5/2014

A scarce saproxylic weevil that feeds on dead wood and is nocturnal and seldom seen. I found a number of these on an ancient hollow Sycamore tree at night in shaded woodland at the Devil’s Spittleful NR but it is usually linked to hollow oak trees.

Enicmus rugosus Latridiidae. (Nationally scarce) 22/5/2014

I found two of these small scavenger beetles on a bracket fungus on a dead standing oak tree at the Devil’s Spittleful NR. The species feeds on various fungi and slime moulds.

06. Platystomos albinus Anthribidae.(Nationally scarce) 7/6/2014

A fungus weevil from the edge of the River Severn at Bewdley. This is an unusual record as it was found feeding on mouldy wood on a decaying ash bough infested with Cramp ball fungus which is usually a habitat of its sister species Platyrhinus resinosus. Perhaps there is some competition between these two species. Usually this species is linked to fungoid oak. In 2012 John Bingham recorded one on oak on the Shropshire side of the Wyre Forest.

07. Clitostethus arcuatus Coccinellidae (RDB1) 23/5/2014

These species was seen breeding again at Crossley Park and Hurcott Wood and I was delighted to find it on Greater Celandine Chelidonium majus at the base of an old hawthorn tree alongside the River Severn at Bewdley and on honeysuckle in woodland alongside the Devil’s Spittleful NR. Definitely spreading and good to see it doing so well (Whitehead & Brown 2012).

08. Cyanostolus aeneus Monotomidae (Nationally rare) 10/7/2014

A predatory riparian species. I found two of these on the wet section of a log jutting out of shallow water on the River Severn at Bewdley. The log was too old to make a positive identification of the type of wood, but when disturbed the one specimen took flight; I don’t think night flight has been recorded in this species before.

09. Bracteon litorale Carabidae (Nationally scarce) 27/7/2014

I found three specimens of this predatory ground beetle active at night on a bare sandy river bank at Bewdley. This species is usually described as diurnal so this was also an interesting observation.

10. Amara praetermissa Carabidae (Nationally scarce) 27/7/2014

A seed-feeding ground beetle. Previously recorded at the Devil’s Spittleful heath, I recorded this one in 2011 at Hartlebury Common in sandy heathland. I was surprised to also come across this species on dry areas of sand banks along the River Severn at Bewdley. It was regularly seen there during the summer months.

11. Dyschirius aeneus Carabidae (Local) 4/7/2014

This is the black colour variation of the species; there is also a brassy version. A predatory ground beetle linked to species of Bledius (Col., Staphylinidae). I found these on bare sand banks along the River Severn at Bewdley.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to John Meiklejohn for his help especially in my early studies. And a big thank you to Paul Whitehead for his help in identifying a lot of these species which has been a big help to me.

Reference

Whitehead, P.F. & Brown, A. 2012. Clitostethus arcuatus (Rossi, 1794) (Col., Coccinellidae) breeding in the Kidderminster area of Worcestershire: overwintering strategies and breeding biology. Worcestershire Record 33:20-22

01. Aegialia sabuleti

02. Dorytomus tremulae

03. Dorytomus tortrix.

04. Xyleborus saxesenni

05. Stereocorynes truncorum

06. Platystomos albinus

07. Clitostethus arcuatus in Bewdley.

08. Rhizophagus aeneus

09. Bracteon literale

10. Amara praetermissa

11. Dyschirius aeneus

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 12-14 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 15-16 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Hornet Rove beetle Velleius dilatatus (F., 1787) (Col., Staphylinidae) at Kidderminster, Worcestershire

Alan Brown

On the 15 June 2014 three specimens of the endangered Hornet Rove Beetle Velleius dilatatus (F.) were found at night at an oak sap-run in woodland alongside the Devil’s Spittleful Nature Reserve, Kidderminster.

Distribution.

Historically this species had only been recorded from the New Forest, Windsor Forest and Moccas Park, but recently it has been recorded further afield at Dartmoor Deer Park, Epping Forest, Norfolk, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire.

Habitat

A sap-run was located on a mature Pedunculate Oak Quercus robur L. (01 & 02) just inside the fringe of a patch of mixed ancient woodland most of which is privately owned. However, a public path leading to the heath through this area allows access to some of the ancient trees, mainly oak, but also birch, Sycamore and lime. A vigil was arranged to see what species turned up at night on the sap-run with interesting results. Two notable species, Cryptarcha strigata (F.) and Cryptarcha undata (Ol.) appeared in numbers with an Epuraea species and a number of Soronia grisea (L.). However, my attention was drawn by a large black rove beetle and I was convinced that it matched the description of Velleius dilatatus, an endangered species. Photographs (03, 04, 05 & 06) were taken and this identification was confirmed by Paul Whitehead who also noted that the sap-run was possibly a Cossus flux but this could not be confirmed.

Behaviour

At least three different individual Hornet Rove Beetles were observed over the following seven nights, sometimes all three together. The white light on my headband torch disturbed them too much to observe any behaviour so I switched to a red light which they were not able to detect. Each night the Hornet Rove Beetles appeared at the sap-run within an hour of it becoming dark and remained there for most of the night. All three were males and always kept some distance between each other at different points around the sap-run. Eventually one male started investigating the sap and at first I thought he was ingesting the sap but it soon became obvious that he was looking for something in it. He then extracted what looked like a white larva, possibly a fly larva although this could not be verified. Later a second beetle retrieved what looked like a fly pupa (07 & 08) but again I could not make a definite identification. However, one larva I did find in the sap was positively identified by Paul Whitehead as Cryptarcha.sp. A daily night time temperature taken at the base of the tree averaged a mild 16° Celsius. Random checks of the sap-run were made during daylight hours but no Velleius dilatatus were seen. After a week the sap-run dried up and that was the end of my observations.

Notes

The Hornet Rove Beetle is an interesting species that spends almost its whole life living in hornet’s nests and is therefore dependent on the success of its host. There are various theories as to what it feeds on, some literature suggests it is parasitic on fly maggots that infest the hornet’s nest or that it feeds on hornet detritus and even on dead or dying hornets. In recent years however the range of the hornet has spread slowly northwards and likewise the range of this rove beetle. Although there is no doubt that this species does most of its feeding within the nest there are obvious indications here that when food is scarce the beetle is drawn to sap-runs to seek alternative prey. It clearly responds well to olefactory cues and can fly well and link the odour of sap to its preferred food. This find, which is a first for Worcestershire, would also seem to indicate that Velleius dilatatus may become more widespread in the future.

01. Oak tree on which sap run was found.

02. Sap-run on oak tree

03. Velleius dilatatus

04. Velleius dilatatus

05. Velleius dilatatus

06. Velleius dilatatus

07. Velleius dilatatus with fly pupa

08. Velleius dilatatus with fly pupa

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 15-16 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 16-18 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Stenelmis canaliculata (Gyllenhal, 1808) (Col., Elmidae) and other aquatic Coleoptera from the Kidderminster and Bewdley areas of Worcestershire

Alan Brown.

On the 24 August, 2014 a single specimen of our largest Riffle Beetle Stenelmis canaliculata was found on a sandbank alongside the River Severn at Bewdley (01 & 02). This is the first Worcestershire record and its identity was confirmed by Paul Whitehead. The current national status is RDB2.

Description: About 5mm long, sculptured on the elytra with four prominent ridges, two of which extend the full length of the elytra, the two inner ridges extending to about halfway down. The pronotum is square with a visible channel down the centre. The tips of the tarsi and apical segments of antennae are red.

Distribution: Recorded from 12 rivers in the last 20 years. First discovered at Lake Windemere in Cumbria, this species has a scattered distribution mainly in fast-flowing rivers in Herefordshire, Devon, Cornwall, Nottinghamshire and Bedfordshire. There is a 1996 record apparently from the Kennet and Avon Canal near Bath North Somerset and a more recent one from the River Findhorn at Moray, Scotland.

History: This species was not added to the British list until 1960 when it was found on a wave-washed shingle bank on Lake Windermere. Since then, records have predominantly come from clean, fast-flowing streams and rivers with gravelly or stony bottoms. Like some other species of elmid it needs well-oxygenated water free of pollution making it a very good indicator of water purity. The beetle itself extracts oxygen from the water and does not need to surface except for a brief period of flight shortly after emergence from its pupa. It is thought to feed on algae attached to stones and prefers deep water.

Notes: Not much is known about this beetle’s life cycle. I found the beetle, in this case an adult female, on sandy ground close to the water’s edge at night. At the time I was looking for ground beetles so I was quite surprised to find it there. It was on a cold autumn evening and the beetle seemed to be moving away from the water. I have seen other elmids above water level so perhaps this was not such an unusual event. With my headband torch I had no difficulty in picking it out despite its small size.

Other Notable Finds

Macronychus quadrituberculatus Müller, 1806. Elmidae: Nationally rare. River Severn, Bewdley, 10 August 2014. The River Severn is a well-known stronghold for this species and I saw them on most of the pieces of decaying wood in shallow water and also occasionally on sandbanks close to the water’s edge. They are quite colourful and unusual with long legs (03).

Pomatinus substriatus (Müller, 1806). Elmidae: Nationally rare. Kidderminster 22 April 2014. Ironically, I recorded this species not in the River Severn, but in the Kidderminster to Cookley section of the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal running alongside Springfield Park. It was spotted at night apparently feeding on algae growing on the canal’s concrete wall about two inches below the water surface. Three other beetles from bare mud alongside a stream running through the park were identified as the dryopids Dryops ernesti des Gozis, 1886 by Paul Whitehead.

Hydrochus elongatus (Schaller, 1783). Hydrophilidae: Nationally scarce. Kidderminster 23 April 2014. A Water Scavenger Beetle found in good numbers in a shaded willow carr bog pool at Springfield Park. The pool itself is a seasonal one tending to dry up in the summertime, but for the last two years has remained full. The pool contains decaying leaves and wood with some mosses. The beetle was easily found at night walking underneath the surface tension of the water and could be scooped up without using a net (04).

Helophorus dorsalis (Marsham, 1802). Hydrophilidae: Nationally scarce Kidderminster 22 April 2010. A Water Scavenger Beetle found during my Ground Beetle survey. This species was found in the same shaded willow carr bog pool at Springfield Park as Hydrochus elongatus and found in the same way. Good numbers were found at night on the water surface.

Acknowledgements

Unfortunately, the 2014 season was to be my last recording for the Worcestershire Biological Records Centre in Worcestershire as I moved elsewhere at the end of the year. It was a memorable six years. Within a two mile radius of Kidderminster, some 101 nationally scarce species of Coleoptera were found together with nine RDB species. There are undoubtedly many more there still to be found. I would like to thank John Meiklejohn, Paul Whitehead, Harry Green, Simon Wood and Rosemary Winnall for the help they gave me during this survey. I am grateful to Paul Whitehead for his constructive assistance in the preparation of this short paper; any factual errors are mine alone. Good luck to everyone for 2015.

01. Stenelmis canaliculata River Severn, Bewdley, 10 August 2014. Alan Brown

02. Stenelmis canaliculata River Severn, Bewdley, 10 August 2014. Alan Brown

03. Macronychus quadrituberculatus River Severn, Bewdley, 10 July 2014. Alan Brown

04. Hydrochus elongates Kidderminster 22 April 2014. Alan Brown

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 16-18 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 20-21 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

The Elm Leaf Hopper Iassus scutellaris (Fieber, 1886) at large in Worcestershire

Gary Farmer

The leaf hopper Iassus lanio will be a familiar insect to anyone who has a mind to shake the branches of oak trees into a net or up-turned brolly. This relatively large leaf hopper (6.5mm to 8.3mm. long) from the family Cicidellidae is wide-spread across Worcestershire and likely to turn up on oak trees almost anywhere in the county (01). However its rarer cousin Iassus scutellaris has become established in the south of the county living in elm hedges.

On 24th July 2014 while surveying hedgerows at Vale Landscape Heritage Trust’s reserve Littleton Meadows I found a small Iassus bug and photographed (02) it because “it didn’t look right”. Its wings were more translucent than any I. lanio that I had seen and it was oddly marked. I checked the British Bugs WebSite and found that it strongly resembled I. scutellaris a Nationally Notable A species found on elm. A check of the distribution on NBN Gateway suggested it to be a species restricted to south east England and East Anglia.

A check on the Auchenorrhyncha Recording Scheme WebSite revealed that the species is now more widely distributed and gives the following account:

“Discovered in Surrey in 1978, this species [Iassus scutlellaris] is now found widely across southern and central England despite its classification as Nationally Notable A. Associated with English Elm Ulmus procera and able to persist on low re-growth following dieback due to Dutch elm disease, it is similar in appearance to the common oak-feeding I. lanio but the colour of the forewings is generally a much brighter lime-green.”

I forwarded my record and photograph to Alan Stewart the Auchenorrhynca Recording Scheme Organiser who gave this cautionary reply:

“…..The distinction between Iassus scutellaris and Iassus lanio is a rather subtle one. …… Externally, it is mainly a question of the pointedness of the vertex (top of head), which I can’t really see on the photo. The fact that it was on elm is highly suggestive of I. scutellaris, but not completely reliable unfortunately as I. lanio can sometimes be found on this tree, although its main host is oak. I have a record of scutellaris from SP24 so not that far from where you found yours. I think this is one of those species for which one would need to examine a specimen to be absolutely sure; getting the right angle on a photo to see the necessary features is extremely difficult …… I would be reluctant to add the records to the recording scheme database without someone inspecting a specimen”.

Unfortunately I had not kept a specimen and a return visit to the location failed to turn up any further examples. However I had been given permission to visit the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust reserve of Hill Court Farm and I took the opportunity to beat some of the hedgerows for invertebrates. I collected several individuals of what I believed to be I scutellaris. I photographed (03) some of the bugs to show the variation and kept one as a specimen. This I pinned alongside a specimen of I.lanio for comparison (04). A clear difference can be seen in the vertex of the two species; I. scutellaris appears to have a longer ‘nose’ because of the shape of the vertex. It is also a smaller insect and in life is a paler more translucent green. The brown markings are variable but distinct from I. lanio. Iassus scutellaris has undoubtedly become established in the county recently but has remained undetected, possibly because of its similarity to its common cousin.

References:

British Bugs WebSite: www.britishbugs.org.uk

Auchenorrhyncha Recording Scheme WebSite: http://www.ledra.co.uk/

Wilson, Michael R. 1981, Identification of European Iassus species (Homoptera: Cicidellidae) with one new species to Britain. Systematic Entomology 6:115-118

Biedermann, R.& Niedringhaus, R. 2009. The Plant- and Leafhoppers of Germany. Identification Keys for all species.

01. Iassus lanio Lower Smite Farm 20 July 2014. Gary Farmer

02. Iassus scutellaris 24 July 2014 Littleton Meadows. Gary Farmer

03. Iassus scutellaris 20 August 2014 Hill Court. Gary Farmer

04. Iassus scutellaris (right) & Iassus lanio (left) pinned specimens. Gary Farmer

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 20-21 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Farmer, Gary - The large pill woodlouse Armadillidium depressum Brandt, 1833 found in Worcestershire

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 25-26 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

The large pill woodlouse Armadillidium depressum Brandt, 1833 found in Worcestershire

Gary Farmer

On 8th July 2014 I noticed a Pill Woodlouse on the wall of the Volunteer Centre in the middle of Evesham. This particular individual was slate-grey and very large and on closer examination its body plates (pleonites) splayed out at the edges. When I tried to capture it, rather than rolling into a ball typical of the pill woodlice, it clamped down with its splayed plates covering its legs. This curious behaviour and large size was reminiscent of a species that I am familiar with from the quarries on Portland, Dorset, Armadillidium depressum, so I decided to take the woodlouse to check it later. I referenced A Key to the Woodlice of Britain & Ireland (Hopkin, 1991) which gives the description for A. depressum “….and often rest in a clamped position in which they remain even when disturbed…….pleonites appear splayed out like a skirt….”. Details shown of the uropods and telson from the rear confirmed that I had found Armadillidium depressum. The images 01, 02, 03, & 03 compare the common Pill Woodlouse Armadillidium vulgare with Armadillidium depressum.

This is a strongly synanthropic species and appears to be going through a range expansion. The Atlas of Woodlice and Waterlice in Britain & Ireland (Gregory, 2009) gives the distribution as having a “distinct south-west bias” and a large population is known to exist around Bristol (B. Westwood pers. comm.). So this is certainly a species to look for around the county’s towns and old churches.

Interestingly Worcestershire Biogical Records Centre holds two other records:

Bredon Hill, SO9438, 1985-1986, Paul Whitehead.

Newland SO791482, 29.06.14, John Dodgson.

References

Hopkin, S.P. 1991. A Key to the Woodlice of Britain and Ireland. Field Studies vol 7 No. 4 Field Studies Council, Shropshire.

Gregory, S. 2009. Woodlice and Waterlice (Isopoda: Oniscidea and Asellota) in Britain and Ireland. NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Oxfordshire.

01. Armadillidium vulgare. Gary Farmer

02. Armadillidium depressum. Gary Farmer

03. Armadillidium vulgare uropods and telson. Gary Farmer

04. Armadillidium depressum uropods and telson. Gary Farmer

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 25-26 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 26 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Two synanthropic Isopods overlooked in Worcestershire

Gary Farmer

Two distinctive woodlice which appear to be strongly synanthropic in Worcestershire are worth looking for in gardens.

Androniscus dentiger Verhoeff, 1908. (01)This is perhaps our most distinctive species being brightly coloured orange or salmon-pink. It is fairly small measuring up to 6mm, fast moving and strongly heliophobic; disappearing quickly when disturbed. This species needs damp conditions and I have only ever found it in deep gravel, under regularly watered plant pots and deep down in the footings of buildings. I am sure it is overlooked in the county because of its choice of habitat so it is worth looking in appropriate places in any garden in limestone areas or close to buildings where lime has leached from mortar or concrete, although I appreciate that not everyone will want to dig out footings just to look for woodlice.

Porcellionides pruinosus (Brandt, 1833). (02). Another distinctive species with long antennae and a fairly narrow body. Porcellionides pruinosus is another fast moving woodlouse with long pale legs which can contrast strongly with the brown/purple body. This is a medium sized species growing up to 12mm but its most distinctive feature is that it often has a bluish powdery bloom. I have only ever seen P. pruinosus in compost bins. Steve Gregory (2009) notes that the species is readily moved around in farmyard manure. So another one to check for in your own gardens, farms and stables.

Reference

Gregory, S. 2009. Woodlice and Waterlice (Isopoda: Oniscidea and Asellota) in Britain and Ireland. NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Oxfordshire.

01. Androniscus dentiger. Gary Farmer

02. Porcellionides pruinosus. Gary Farmer

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 26 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 8-9 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Wasps in a box: Dolichovespula sylvestris using a bird nest box

Gary Farmer

I was asked to advise on the action to take regarding a wasp nest in a bird box on a house wall in Bishampton (01, 02 & 03). I was curious as I couldn’t recall seeing wasp nests in bird boxes other than Hornets Vespa crabro. When I first saw the nest on 20th June 2014 the wasps were already very active and were extending their remarkable ‘paper’ structure over the outside of the bird box. I was able to take a few reference pictures and could see that they were in fact Tree Wasps Dolichovespula sylvestris. I had not seen the nest of this species before and was unable to find references in ‘the books’ so I did an internet search on “tree wasp nest” to see if this was usual behaviour for them. Unfortunately the internet is more interested in exterminating our black and yellow hymenopteran neighbours than it is on sharing real information. Site after site reported that tree wasps are aggressive and gave details of how to deal with a nest. Sadly it seems that any wasp that nests in trees or bushes is classed as a tree wasp and seen as something to be feared and destroyed. In my experience D. sylvestris is by far the least aggressive of the social wasps and I was happily able to persuade the home owner to let the wasps live. A little later in the summer I was given an update that the wasps were busy eating fence posts and patio furniture and by 17th July the nest was finished and the colony had dispersed.

I have since been able to find reference to various wasp nests in Bees and Wasps by Jiri Zahradnik in which he states that Tree Wasp nests are “…built most often under eaves, in bird boxes, in tree tops or partly underground”. Interestingly in the description of the wasp he notes “It does not bother man and does not enter his homes.” Thank goodness for books.

Reference:

Zahradnik, J. 1998. Bees and Wasps (English edition), Blitz Editions, Leicester.

01. Tree Wasp Dolichovespula sylvestris nest in bird box. Gary Farmer

02. Tree Wasp Dolichovespula sylvestris nest in bird box

03. Tree Wasp Dolichovespula sylvestris nest in bird box. Gary Farmer.

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 8-9 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 32-33 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Albino Starling at Hampton, Evesham, 2014

Harry Green

On 18 June 2014 Betty and Toby Keane saw a ‘white bird’ in their garden in Hampton Evesham (01). It was a nearly perfect albino Starling in brand new barely worn plumage of a juvenile not long fledged and an albino but for the dark eyes and legs. A picture and note appeared in the Cotswold and Vale Magazine (August 2014 issue 179) and shortly afterwards Anne Jordan also from Hampton reported presumably the same bird with four normally coloured siblings being fed by adults on her lawn (02, 03, 04). The albino was ‘the boss ’demanding food from parents before its siblings. Later in summer both albino and the other juveniles left the gardens and presumably joined other starlings in the usual late summer flocks.

In mid-July Donna Saxton reported a very similar bird perched on a TV aerial in Charlton, about two miles from Hampton. (05). Perhaps the same bird although the quality of the picture was too poor for close comparison (05).

Albino Starlings are not often reported.

01. Albino juvenile starling Hampton, Evesham June 2014. Toby Keane

02. Albino starling fed by parent Hampton, Evesham June 2014. Anne Jordan

03. Albino starling juvenile Hampton, Evesham June 2014. Anne Jordan.

__

__

04. Albino starling juvenile with normal siblings Hampton, Evesham June 2014. Anne Jordan

05. Albino starling at Charlton July 2014. Donna Saxton

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 32-33 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 67-68 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Field recording days 2014

Harry Green

Three special field recording days were arranged for the summer of 2014 organised by Worcestershire Recorders and supported by Worcestershire Biological Records Centre, the latter managing the records on their database.

Black House Wood, Suckley, 7th June 2014, central grid reference SO733521.

An ancient woodland site lying on a Silurian limestone ridge. The wood is well-known for a rich flora but records for other groups relatively few in number. An important site for both Small-leaved and Large-leaved lime. Partly planted with conifers in the past. The wood is being purchased by Worcestershire Wildlife Trust as a reserve and the Trust kindly gave permission to visit.

Pound Green Common, Button Oak, Wyre Forest, 5th July 2014, central grid reference SO754789

Pound Green Common is an important heathland site in the process of rehabilitation and recently acquired by Worcestershire Wildlife Trust. Many thanks for Worcestershire Wildlife Trust for permission to visit.

Grafton Wood, Grafton Flyford, 2nd August 2014, central grid reference SO972560. A visit to a large area cleared of conifers three years previously.

Grafton Wood is an ancient woodland site managed and jointly owned by Worcestershire Wildlife Trust and Butterfly Conservation for many years. Three years previously two large blocks of conifers were clear-felled and this visit was aimed at those areas. Many thanks to both owners for giving permission to visit.

The striking feature of all three recording days was rain. It was raining when we arrived at Black House Wood and only stopped for a short period in the afternoon (pictures 01, 02, 03). Despite this over 300 records were sent to WBRC. The rain had stopped when we arrived at Pound Green Common and the day was cloudy with occasional shafts of sunshine. However the vegetation was wet making invertebrate sampling difficult (04, 05, 06). We arrived at Grafton Wood after a night of torrential rain which slowly stopped as we crossed the fields to the wood. Again the vegetation was extremely wet making invertebrate recording difficult (07, 08). By far the wettest recording year we have ever experienced.

The aim of the field recording days is to obtain as many records of as many groups of plants and animals as possible to give a ‘snapshot’ for the day. Whether we succeed in this aim or not depends on who attends on the day and the weather conditions. 25-27 people booked for each recording day 2014 but the weather took its toll and attendance was 14, 21 and 9 people. Nevertheless a good range of expertise was present with over 300 records for the first two days but around half that for the third day.

01. Mick Blythe and Dave Scott Black House wood. Nicki Farmer.

02. Lunch Black House wood. Nicki Farmer

03. Invertebrate sampling with brolly. Nicki Farmer

04. Recorders at Pound Green Common. Nicki Farmer.

05. Recording day 05July2014 Pound Green Common Mike Averill & Dave Scott & Brett Westwood. Harry Green

06. Recording day 05July2014 Pound Green Common, Rosemary Winnall & Brett Westwood. Harry Green

07. Grafton Wood recording day in wet clearfell. Harry Green.

08. Grafton Wood recording day lunch in iron storage container. Harry Green.

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 67-68 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 24-25 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

More records of Western Conifer Seed Bug Leptoglossus occidentalis in Worcestershire

Harry Green

Since John Holder’s record on 4th December 2011 (Holder 2011) there have been occasional further records including the following two.

Jean Young wrote “We came across this lovely specimen of a Western Conifer Seed bug in our bedroom curtains at Besford Court Estate on the morning of 23 October 2013. The window was open overnight so presumably it had come in looking for a cosy place to overwinter. We have several conifers on the estate. We have not seen any others since our ‘indoors’ sighting”. Besford Court Estate Grid Reference SO 9148 4533. (01, 02, 03)

And John Cox wrote “I attach a photo of, I think, a Western Conifer Seed Bug found on our landing carpet on the evening of 30 December 2014 Sadly it was lacking one hind leg”. Kidderminster SO 845756. (04)

It is worth looking out for this large bug. Its origin is explained in the Editor’s Note added to John Holder’s original note and is copied below.

Editor’s note

The British Bugs website http://www.britishbugs.org.uk/heteroptera/Coreidae/leptoglossus_occidentalis.html states “Native to the USA and introduced into Europe in 1999, it has since spread rapidly and during 2008-2010 influxes of immigrants were reported from the coast of southern England, with a wide scatter of records inland. The bug feeds on pines and is likely to become established here; nymphs have been found at several locations. It is attracted to light and may enter buildings in search of hibernation sites in the autumn”. http://www.britishbugs.org.uk/heteroptera/Coreidae/Leptoglossus_occidentalis.pdf a fact sheet from Forest Research gives more information.

Reference

Holder, J. 2011. Western Conifer Seed Bug Leptoglossus occidentalis in Droitwich. Worcestershire Record 31:21.

01. Western Conifer Seed Bug 23 October 2013. Jean Young.

02. Western Conifer Seed Bug 23 October 2013. Jean Young.

03. Western Conifer Seed Bug 23 October 2013. Jean Young.

04. Western Conifer seed bug Kidderminster 30 December 2014. John Cox.

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 24-25 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 28-29 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Bryophytes of Hollybed Farm, Malvern

Ann Hill

Worcestershire Bryophyte Group and the Border Bryologists held a joint bryophyte recording day on Sunday 16th March 2014 at Hollybed Farm, Malvern. Hollybed Farm is a newly established Worcestershire Wildlife Trust grassland reserve of 16ha with a mixture of limestone, neutral and wet grassland, a small valley with calcareous banks, damp woodland, scrub and open grassy areas, small fields of rough calcareous grassland, agriculturally improved fields bordered by hedgerows and the remnants of an old orchard. Fifty bryophyte species were recorded during the day.

The greatest bryophyte interest was found in the damp woodland along the stream valley and it was here that the most interesting bryophyte record of the day was made. The liverwort Cololejeunea minutissima Minute Pouncewort (01) was found by Rita Holmes growing on ageing coppiced hazel at the south-eastern end of the valley. The liverwort is minute (plants to 4(8) mm long with leafy shoots 250-500ums wide) and there were only two previous records for the county: in 2003 at Wissett’s Wood and in 2004 at Broad Down, Malvern.

Another interesting record along the stream valley was of Palustriella falcataClaw-leaved Hook-moss, a pleurocarpous moss indicative of base-rich wet habitats, wet calcareous rocks and seepages. There are very few records of Palustriella falcata in VC37. In the same habitat Oxyrrhynchium schleicheriTwist-tip Feather-moss was also recorded: this is a pleurocarpous moss of well-drained soil on banks by rivers, streams, tracks and lanes, and has been infrequently recorded in the county.

General bryophyte cover was patchy along the stream valley and varied in response to small-scale changes in topography and moisture. In places there was extensive cover of Brachythecium rutabulum Rough-stalked Feather-moss (and in wetter places Brachythecium rivulare River Feather-moss) frequently growing with Kindbergia praelonga Common Feather-moss over the bare soil.

Epiphytic mosses growing on tree trunks and inclined branches included frequent Orthotrichum affine Wood Bristle-moss and more rarely other species of Orthotrichum such as O. diaphanum White-tipped Bristle-moss, O. lyellii Lyell’s Bristle-moss (02) and O. pulchellum Elegant Bristle-moss. Ulota phyllantha Frizzled Pincushion (03), Zygodon viridissimus Green Yoke-moss and Cryphaea heteromalla Lateral Cryphaea were also noted as were the liverworts Frullania dilatata Dilated Scalewort and locally abundant Metzgeria furcata Forked Veilwort.

Bryophytes were scarce in the grassland habitat. A few arable bryophytes such as Barbula unguiculata Bird’s-claw Beard-moss, Bryum dichotomumBicoloured Bryum and B. subapiculatum Lesser Potato Bryum were recorded around the field margins. VC37 only has a very few records of the acrocarpous moss B. subapiculatum possibly because certain identification requires you to free the rhizoids of soil in order to examine the tiny tubers (like minute potatoes) attached to the rhizoids. Bryophytes of arable fields are small and inconspicuous and tricky to identify until you “get your eye in”. Funaria hygrometrica Common Cord-moss, a moss of disturbed and cultivated ground and often found on sites of fires was recorded on bare soil in the corner of a field. Of interest were the large dark green patches of the leafy liverwort Porella platyphylla Wall Scalewort that covered the base of an old ash tree in a hedgerow of one of the fields.

The old orchard was found to be of little interest for bryophytes: possibly because of past management practices or because the fruit trees were pear rather than apple (apple trees have a base-rich bark). However, Hypnum cupressiforme Cypress-leaved Plait Moss was locally abundant on the bark of some of the old trees and generated an interesting discussion about the complexities and identification of species of the Hypnum cupressiformecomplex.

Overall, the farm had a reasonable diversity of bryophytes and we had a very enjoyable and interesting recording day and enjoyed beautiful warm weather.

Additionally, in the morning we saw an interesting and unusual cloud formation over Starling Bank. The cloud was a Lenticular cloud Altocumulus lenticularis – a type of lens-shaped cloud that sometimes forms over mountains and high ground (04 photo taken by Bill Dykes).

We also recorded an adult slow-worm basking on a south-facing bank overlooking the stream valley.

The group was led by Mark Lawley and Ann Hill and the bryologists were Barbara Marshall, Bill Dykes, Des Marshall, Gary Powell, Gillian Driver, John Marshall, Mary Singleton, Pam Parkes, Rachel Kempson, Ralph Martin, Richard Finch, Rita Holmes, Roger Parkes, Tessa Carrick, Wendy Clarke and Xiaoqing Li.

Worcestershire Bryophyte Group is a small informal group that goes out to Worcestershire sites to record and learn about bryophytes. Our broad aim is to assist everyone, especially those who are new to mosses and liverworts, to become more experienced and confident at identifying bryophytes. Beginners are always very welcome, the only equipment needed is a hand lens (x10 or x20) and some paper packets for collecting specimens. Below are dates for our next planned field excursions. If you are interested in joining us on either of the field trips please contact me at ann@gaehill.f9.co.uk and I will let you know full details.

Table 1. List of Bryophyte species recorded at Hollybed Farm, Malvern 16thMarch 2014.

| Latin Name | English Name |

| Mosses | |

| Amblystegium serpens var. serpens | Creeping Feather-moss |

| Barbula unguiculata | Bird’s-claw Beard-moss |

| Brachythecium rivulare | River Feather-moss |

| Brachythecium rutabulum | Rough-stalked Feather-moss |

| Bryum capillare | Capillary Thread-moss |

| Atrichum undulatum var. undulatum | Common Smoothcap |

| Platyhypnidium riparioides | Long-beaked Water Feather-moss |

| Bryum dichotomum | Bicoloured Bryum |

| Bryum subapiculatum | Lesser Potato Bryum |

| Cryphaea heteromalla | Lateral Cryphaea |

| Dicranoweisia cirrata | Common Pincushion |

| Didymodon insulanus | Cylindric Beard-moss |

| Didymodon rigidulus | Rigid Beard-moss |

| Fissidens bryoides var. bryoides | Lesser Pocket-moss |

| Fissidens taxifolius var. taxifolius | Common Pocket-moss |

| Funaria hygrometrica | Common Cord-moss |

| Grimmia pulvinata | Grey-cushioned Grimmia |

| Hygroamblystegium tenax | Fountain Feather-moss |

| Hypnum cupressiforme var. cupressiforme | Cypress-leaved Plait moss |

| Hypnum cupressiforme var. resupinatum | Supine Plait-moss |

| Isothecium myosuroides var. myosuroides | Slender Mouse-tail Moss |

| Kindbergia praelonga | Common Feather-moss |

| Leptodictyum riparium | Kneiff’s Feather-moss |

| Mnium hornum | Swan’s-neck Thyme-moss |

| Neckera complanata | Flat Neckera |

| Orthodontium lineare | Cape Thread-moss |

| Orthotrichum affine | Wood Bristle-moss |

| Orthotrichum diaphanum | White-tipped Bristle-moss |

| Orthotrichum lyellii | Lyell’s Bristle-moss |

| Orthotrichum pulchellum | Elegant Bristle-moss |

| Oxyrrhynchium hians | Swartz’s Feather-moss |

| Oxyrrhynchium pumilum | Dwarf Feather-moss |

| Oxyrrhynchium schleicheri | Twist-tip Feather-moss |

| Palustriella falcata | Claw-leaved Hook-moss |

| Plagiomnium undulatum | Hart’s-tongue Thyme-moss |

| Rhynchostegium confertum | Clustered Feather-moss |

| Syntrichia montana | Intermediate Screw-moss |

| Thamnobryum alopecurum | Fox-tail Feather-moss |

| Tortula muralis | Wall Screw-moss |

| Ulota species | |

| Ulota phyllantha | Frizzled Pincushion |

| Zygodon viridissimus var. viridissimus | Green Yoke-moss |

| Liverworts | |

| Cololejeunea minutissima | Minute Pouncewort |

| Conocephalum conicum | Great Scented Liverwort |

| Frullania dilatata | Dilated Scalewort |

| Lophocolea bidentata | Bifid Crestwort |

| Lophocolea heterophylla | Variable-leaved Crestwort |

| Metzgeria furcata | Forked Veilwort |

| Pellia epiphylla | Overleaf Pellia |

| Porella platyphylla | Wall Scalewort |

| 01. Cololejeunea minutissima Minute Pouncewort. Ann Hill |

| 02. Orthotrichum Lyellii Lyell’s Bristle-moss. Ann Hill |

| 03. Ulota phyllantha Frizzled Pincushion. Ann Hill |

| 04. Lenticular cloud Altocumulus lenticularis. Bill Dykes |

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 28-29 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 22 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

An interesting cellar with bats, birds and butterflies

Garth Lowe

My long term study of swallows in Alfrick on the edge of west Worcestershire, takes me into odd places including a large cellar where Swallows have been nesting for many years. In the middle of August 2014 while checking a nest that had already produced chicks, the owner told me about other surprising occupants.

In the gloom at the back section my torch lit up a Lesser Horseshoe Bat hanging like the proverbial plum! (01). It failed to wake up for the few minutes that we were there, and was obviously well into “shut down mode”. Small movements from it indicated it was definitely alive: but why had it gone into hibernation mode in a summer month? The weather had cooled down from previous weeks but not so critical that it would send a bat to sleep. By the pile of droppings beneath it, this must be a favourite place for it to hang out safely.

Right at the back of the cellar more sleeping creatures were found hanging on the ceiling. There must have been half a dozen each of Small Tortoiseshell and Peacock butterflies looking like they were heading for a very long wait till spring. It may be that having located the cellar they reawaken on good autumn days and go outside to top up on available nectar sources. One hopes the sleeping bat does not wake up to find them for a snack!

Sleeping with the butterflies were also a few of the only moth we have that hibernates in the adult form, the Herald; they too have a long wait until spring arrives. This is a fairly common moth with distinctive wing shape and wing markings and can also be the first moth to be seen every year and possibly also the last (02).

One month later another visit was made to check the Swallows had all flown, only to find probably the same bat still there. This time it was fully awake and found hanging in another spot and then fluttered around in the gloom. It appears that when it goes torpid it must hang in exactly the same place as there was a distinct black patch of dropping on the ground beneath it.

On this visit there were in fact butterfly wings lying around, one being from a Red Admiral, so it does look as though the bat snacks on them, probably when they fly in during the day and the bat is awake and picks them up on its echo location system! A better inspection is needed when the bat is not in residence to comply with the restrictions on people entering a known bat roost. Other butterflies and Heralds were still clinging to the ceiling, so they may have been the lucky ones that flew in or out while the bat was fully asleep. One Peacock was aroused by my movement and maybe torchlight and it did the noisy flicking of wings and flashing the beautiful eye spots that they do to deter predators while they are torpid.

A final check at the end of October found a single Tortoiseshell and 16 Herald moths: there were probably more tucked away in the timbers, but the fact there were also two Lesser Horseshoes fast asleep and not wanting to disturb them time to explore further was limited.

Other temporary inhabitants of the cellar back in the spring had been a family of Wrens. The lazy or smart male, whichever way you look at it, had used an old swallow nest attached to a beam, and only had to put a roof on it to try and attract a female. Male Wrens are of course quite unusual in as the male does the building of more than one nest and takes the lady of his choice on a round of inspections! This time he was successful in persuading her that this was a secure site. Interestingly both the Wren and a pair of Swallows nested very close together, with only a main supporting beam between them!

In the past both Robins and Blackbirds have also found the cellar a safe place to rear a family, so that makes a grand total of seven species using this damp gloomy underground space with an approximately five foot wide door at the bottom of some steps.

01. Lesser Horseshoe Bat hanging like the proverbial plum. Garth Lowe

02 Peacock butterfly and Herald moths. Garth Lowe.

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 22 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 47 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

New record in Worcestershire – Chamaesyce serpens

Bert Reid

Chamaesyce serpens, previously known as Euphorbia serpens, is a species in the Spurge family Euphorbiaceae known by the common name matted sandmat. Originally native to South America,

It is now found across much of the world as an introduced weed. It forms a mat of prostrate stems which root at nodes where the stem comes in contact with the ground. The detailed structure of Spurge flowers are always hard to understand, even in our common species, and to me they are impossible with tiny unfamiliar aliens.

On the 29th August 2014 I was recording plants along Longdon Hill near Wickhamford, Evesham. I finished my recording and was walking back to where my car was parked when I passed by the garden center Vale Exotics. In a fit of curiosity I popped in looking at the Tree Ferns and other interesting plants and happened to notice a big patch of weeds stretching on to the path around the display. I didn’t recognize what it was, so I spoke to the staff there who said that they certainly didn’t plant it there and had regularly tried to get rid of it. I collected a bit to take home, but failed to identify it. My eyesight does not allow me to use a camera so I asked Harry Green to get a close-up photo of the plants I collected. I could then see the details on my computer, but after ruling out all the plants I suspected, I decided to send Harry’s photos (01, 02) to Quentin Groom, an expert at the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland.

Next morning I got a reply determining the identity. The reply made me feel a bit better for my failure, because I had never even heard of the species or even the current genus. The only earlier records in Britain I have found were rare (less than 5 sites) sporadic plants from imported bird seed and / or wool waste on tips.

01. Vale Exotics with mat of Chamaesyce serpens. Harry Green

02. Highly magnified section of Chamaesyce serpens. Harry Green

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 47 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

Worcestershire Record | 37 (November 2014) page: 48-50 | Worcestershire Biological Records Centre & Worcestershire Recorders

The Flora of Worcestershire – Notes and Additions

Bert Reid

I cannot write an unbiased critique of Roger Maskew’s book, The Flora of Worcestershire 2014, because I have been strongly involved in the Worcestershire Flora Project from the inaugural meeting in 1987, through the creation of a charity in 1994, up to my withdrawal from the management of the project and charity in 2005. In my letter to the Committee, I wrote that “Both Roger and I are strong-willed people with firm ideas, and we disagree about many aspects of the project. The resolution of such differences can only occur if there is a wider body to which the issues and arguments can be referred. If this is to be a collegiate project, I think that it needs collegiate governance.” I also wrote “Any removal or addition or maps would require a full rewrite of the species concerned and I would not be happy for this to be carried out by anyone else. Individual authors must have the final say over accounts published in their name”.

The author will thus not be surprised that I have some reservations about the book, since we have discussed most of these over a number of years. The book is too bulky and the quality of the binding is far from ideal. Although I agree with Roger that the book should be made available in printed form, I hope that the book will be made available on the internet (as a pdf) as soon as is practical. The book would be easier to use if an Ordnance Survey Map of the County was included. Not everyone knows where the places named in the accounts are. I do not think that the brief mention of NVC classifications is adequate. I know that the author does not appreciate them, but many international and professional readers will, and I don’t see the problem with a brief entry like my soil summary in the first chapter. We had long arguments over maps, and I eventually agreed with the compromise, but am disappointed with the quality of the maps – I can hardly see the hectad lines, but that may be my declining eyesight! I would have preferred the inclusion of Charophytes, which are covered by BSBI and are well known in the county: our records include nationally important species. The Extinctions and Changes chapter was originally written by me but the changes and rewrites by Roger made the account so confused and difficult to follow that I refused to be published as a joint author.

The proof reading is generally excellent, but it was unfortunate that the rediscovery of Pyrola minor was attributed to P.L. Reake rather than P.L. Reade. I think that brief curriculum vitae of the major contributors to the flora (including the author) should be added. We know how difficult it is to find any details of historic people from herbaria specimens and the like and we ought to assist future readers to find a little bit out about us.

The book as a whole is curiously unbalanced and old fashioned. With little or no coverage of plant communities, landscape history, bryophytes, archaeophytes, IUCN status etc the book could have been written in the 1980s. The 2013 Flora of Birmingham and the Black Country is very different in coverage but is a good example of how a lot of data (and photographs) can be presented in an attractive and readable way.

Post-flora Records

There have been several species found since the publication of the flora. I am ignoring the Stoneworts, as these need a separate article at a later date. The taxa below are in alphabetical order of Latin name, rather than the scientific sequence used in the book. Some of the taxa included here are not recent records but were excluded from the book as being “hortal species and cultivars in gardens, the cultivated parts of churchyards, cemeteries, allotments, urban parks and planting schemes…” but these rules are not followed consistently. Roger Maskew’s record for Malus transitoria clearly planted on a roadside opposite the Commandery Museum in Worcester is included (with a photograph!) yet records such as the first species below are not included. Here I include such plants. All the records are introduced unless otherwise noted.

Acer platanoides Schwedleri group. Purple Norway-maple.

The Purple Norway-maple is a clear introduction, but Keith Barnett noted numerous seedlings from a large planted tree in the communal garden at Lansdowne Crescent, Malvern, in April 2003, grid SO7846. With clear evidence of reseeding and probable naturalisation it is worth including. One site noted.

Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. Prince’s-feather

Princes-feather is a domestic species, developed in cultivation as an attractive garden plant related to the more common A. caudatus, Love-lies-bleeding. The only record away from a garden was by Keith Barnett, who found a single plant in flower on the pavement of Abbey Road, Malvern in August 2010, SO7745.

Anthemis austriaca Jacq. Austrian Chamomile

This rare but increasing alien was first found by A.W. Reid in September 2009. It was noted with a very unusual mix of plants of clearly differing origins on an earth bank between the old and new roads on the B4624 Evesham Road, SP028459. There were two non-flowering plants, confirmed by C.P. Poland and E.J. Clement from a photo of a grown-on flowering plant. The plants flowered again in 2010 and my experience allowed me to confirm the next record, this time in 2012 by Keith Barnet on the B4211, Hanley Castle, SO839423. About 100 plants were flowering there on a grass or wildflower seeded verge.

Apium graveolens var. dulce (Miller) DC Celery.

This is another record from the earth bank between the old and new roads on the B4624 Evesham Road, this time in 2010. The grid reference and recorder were as my Anthemis austriaca but this plant clearly originated from market garden soil.

Betula utilis var. jacquemontii Spach. Jacquemont’s Birch.

This unusual tree was obviously planted in the Pershore Bridge picnic area (SO952449). It was recorded by A.W. Reid in 2010. It is an interesting and attractive tree with brilliant white bark, and is becoming popular in roadside plantings.

Brassica “Mizuana” Japanese Greens.

This is yet another record by A.W. Reid from the earth bank between the old and new roads on the B4624 Evesham Road in 2010 with the very close grid reference of SP027460. This plant is easily recognised as a market garden plant grown for salads but I discussed the find with Tim Rich to see if he could give me an accepted Latin name: in his reply he says he is “inclined towards rapa as the ‘species’ but I really don’t know”.

Calla palustris L. Bog Arum

Bog Arum is described by Stace as “Intrd-natd; grown for ornament, persistent and spreading in marshy ground and shallow ponds”. We only have a single record, when Mr J.J. Bowley noted it as planted in Kings Heath Park pond, SP067816, date February 1990.

Capsicum annuum L. Sweet (Chilli) Pepper

This is a very strange record by A.W. Reid from an arable field north of Bredons Norton, SO932396, date July 2013. I was walking along the track looking for arable weeds when I noticed a patch of disturbed ground about 10m into a field of rape. I struggled through the rape to investigate and was astonished to see about 20 Chill Peppers growing in fruit. I then walked all around the field but found no more Chillies, though there were a few Phacelia, Buckwheat and White Mustard along the more distant edges. The source of the plants is uncertain, but I can only guess that a nearby neighbour had cleared out a domestic greenhouse and thrown the rubbish into the rape field.

Chamaesyce serpens (Knuth) Knuth. Matted Sand-mat